My contribution to The Lady with the Torch: Columbia Pictures 1929-1959, edited by Ehsan Khoshbakht, and published this month to accompany the Locarno Film Festival’s retrospective curated by Ehsan.

It’s fitting that Andre de Toth’s spikey, achronological, and boisterously all-over-the-place autobiography of 1994 lacks an index and is entitled Fragments: Portraits from the Inside. Given his wanderlust, the somewhat splintered career it produced, and his resistance to being pinned down by the expectations of others, it’s hardly surprising that recognition of de Toth as an auteur arrived only belatedly, at least in the English-speaking world, decades after the publication of Andrew Sarris’s The American Cinema. Among the recipients in Fragments’ two pages of “dedications” are his seven wives (one of whom was Veronica Lake) and nineteen children or stepchildren, adding to the burgeoning list of all the people, forces, and inclinations that subdivided him, leading to many paradoxes as well as some confusions.

De Toth’s boastful account of his Hungarian childhood largely consists of descriptions of both the schools he got expelled from and the pranks leading to each of his expulsions. From the outset, he establishes himself as someone who loves to tussle, with friends as well as adversaries. His bigger-than-life bluster, with reams of supposedly remembered dialogue punctuating every episode in detail, is always entertaining and never completely believable. After his youthful ambitions veered from art to playwriting (the latter of which inspired his country’s most famous playwright at the time, Ferenc Molnár, to become his cranky mentor), he became a writer, director, 2nd unit director, producer, actor, and all-around problem-solver in movies — starting out in Hungary before proceeding to other countries. After diverse stints with the Korda family (sustained by his friendships with Vincent and Zoltan rather than Alexander) and many wartime adventures, he emigrated to Hollywood in the early 1940s while the war was still raging.

Adding to all this historical, professional, and geographical mobility (accompanied by an ongoing penchant for camera movement) was his determination not to be held down by any studio contract and to remain, as in the Westerns and noirs that he often fancied, a gun for hire. (One of his proudest accomplishments was cowriting the classic anti-Western The Gunfighter [1950], before reportedly refusing to direct it after Gregory Peck was cast in the title role.) The hyperbolically dissimilar first two features that he directed at Columbia were a pedestrian, formulaic action quickie (Passport to Suez, 1943—the eleventh entry in the Lone Wolf series and the last to star Warren William, labeled by de Toth as his “key to the door of Hollywood”.) and a powerful, visionary piece of wartime agitprop (None Shall Escape, 1944—set at a postwar tribunal for war crimes in Poland where Wilhelm Grimm, a Nazi functionary played by Canadian actor Alexander Knox, is tried and convicted).

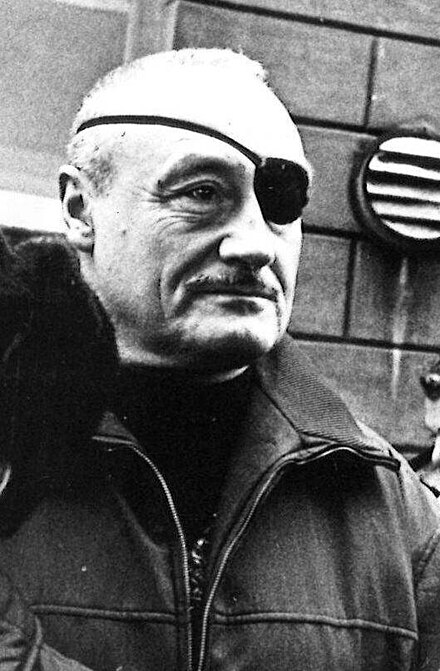

One way of identifying de Toth’s more personal films is gauging how much ambiguity, ambivalence, and/or complexity informs their characters. Knox plays villains in None Shall Escape, Man in the Saddle (1951), and The Two-Headed Spy, yet de Toth takes care to show their vulnerability with a modicum of sympathy in all three — especially in the first two, where a lack of sexual self-confidence is made to seem the cause of their villainy. Randolph Scott’s heroes in both Man in the Saddle and The Stranger Wore a Gun (1953) are presented as obscurely motivated moral ciphers — which makes him more interesting in the former but less compelling in the latter, where he’s often upstaged by all the weapons thrown at the camera for 3-D effects. (Despite the fact that de Toth lost an eye in a childhood accident and wore an eyepatch, he was often considered the best and most thoughtful 3-D director after the success of House of Wax [1953]. He even regarded the process as “the unification of theater and film”, making viewers feel more present in a film’s action.)

Another aspect of de Toth’s personal investments in some of his films is reflected in his memoir’s subtitle, Portraits from the Inside. For example, he recounts telling Harry Cohn, Columbia’s. vulgar and tyrannical studio boss, that he deliberately sabotaged Cohn’s plan for Paul Lukas to star as the Nazi antihero of None Shall Escape because he didn’t want a “good” actor in the part: “None Shall Escape shouldn’t be acted, it should be felt, thought, lived. An ugly slice of life. Real, the truth as it was. As it is now. I lived through it. The faces shouldn’t be déjà vu.” He also enjoys recounting a stormy phone conversation with Cohn’s brother Jack, based in New York to handle Columbia’s distribution, about the planned inclusion of four black judges on the postwar tribunal for war crimes (presciently called the United Nations, well before that institution was founded, and almost three years before the Nuremberg trials), which he says will make it impossible to show the film in the American South. At a subsequent shouting match with Harry, a compromise is reached to include only one black judge, which de Toth later concludes makes the gesture and detail even more effective — though truthfully, it’s so fleeting in the released film that it’s debatable whether it was even noticed in 1944. And in fact, de Toth winds up

expressing admiration and even affection for Harry Cohn as “a sensitive human being” who hid behind his crudeness.

Passport to Suez, None Shall Escape, and The Two-Headed Spy (1958) all have Nazi villains, but the resemblances stop there. The latter of these, an effective and efficient thriller about a British spy who became a Nazi officer (Jack Hawkins), was scripted by three uncredited blacklisted writers (Michael Wilson, Alfred Levitt, and Dalton Trumbo), and the second was scripted by Lester Cole (who was credited, but subsequently became one of the blacklisted Hollywood Ten) from a story by Alfred Neumann and Joseph Than that received an Oscar nomination. All three of de Toth’s Columbia Westerns—Man in the Saddle, Last of the Comanches (1953), and The Stranger Wore a Gun — were written by the less distinguished and distinctive Kenneth Gamet. The second of these was in fact a remake of Sahara (1943), a Humphrey Bogart action war picture that was the last of the Korda productions that de Toth worked on before he moved to Hollywood.

Converting Nazi villains into Comanche “savages” (as an opening intertitle chooses to call them) was relatively unexceptional for that period, especially in a fairly routine adventure story about a small group of people trekking across a vast desert in search of water, led by a U.S. cavalry officer (Broderick Crawford).

None Shall Escape, by contrast, qualifies as one of de Toth’s key films alongside Ramrod (1947), Pitfall (1948), Crime Wave (1954) and Day of the Outlaw (1959) –- though perhaps more as an act of witness than as a work of art. (It does, however, offer many signs of artistry, starting with Lee Garmes’ lush cinematography.) Unlike the five other titles cited, it practically invents a genre of its own by couching its art-movie agitprop in the terms of science fiction. As Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville would do two decades later, None Shall Escape — its title derived from a Franklin Roosevelt speech about Nazi crimes — plants a sharp look at the recent past inside the recent (or soon to materialize) future. One might even say it mixes tenses in order to address the present.

I haven’t seen any of de Toth’s five Hungarian features, but None Shall Escape clearly stands apart from his other work in Hollywood, and not only because it feels more European, managing to get through a fairly simple storyline without a hero and often functioning like a newsreel designed to convey the daily horrors of life under Nazism as fully as it knows how to do, offering itself as a principled human gesture enhanced by the eloquence of its anger. (“Is there any greater degradation,” declares one victimized Jew, “than to be ‘tolerated’?”)

And for De Toth — who was once obliged to film Poles standing in a bread line on a city street while their Nazi conquerors kept ordering them to smile for the camera — the film was literally and personally an act of witness. (After filming newsreels in Hungary when the Nazis invaded Poland, he was sent to cover the German-Polish front.)

Significantly, unlike most newsreels, it deals only with minor functionaries, not with any big shots. Hitler remains in the wings, noted as he writes Mein Kampf a few rooms away, but is neither heard nor seen. (He’s shown from behind as well as heard many times in The Two-Headed Spy, however, always sputtering with rage as he barks out his orders, which paradoxically but understandably makes him seem less real.) Sticking to ordinary people in None Shall Escape makes its grim (or Grimm) lessons less mythical and easier to follow because it often registers as a personal address — history delivered as word-of-mouth. Writing in Tablet, Thomas Doherty aptly called it “Hollywood’s First Holocaust Film” and a “prescient B-movie Nazi noir”.

The critic who has taught me the most about de Toth’s auteurist profile, the late Bertrand Tavernier, confounds me with the following remark about the first of de Toth’s Columbia Westerns (1951): “At the end of Man in the Saddle, Randolph Scott wounds Alexander Knox again and again before finishing him off –- a moment of rare sadism in Scott’s filmography. (De Toth, by some strange coincidence, has just telephoned me and confirms that he had to battle with his star in order to film these shots.)” Furthermore, in 50 ans du cinéma américain (coauthored by Jean-Pierre Coursodon), Tavernier alludes to the same violence. Yet in the version of the film that I’ve seen —mindeed, in all the versions I’ve found posted on YouTube — Scott isn’t shown wounding Knox at all. We see Knox being shot once by another character, frontally, as Knox descends a hotel staircase, with Scott following close behind him. The jerky cuts in this sequence originally made me conclude that some act of American censorship must have removed Scott’s violence and even some of its motivations. What could have made this violence even more shocking is that it follows a nonviolent agreement between Knox and Scott in a hotel room, after the sexual rivalry arising from Joan Leslie, Scott’s girlfriend, having married Knox for strictly mercenary reasons, which has dominated all the preceding action. Thanks to de Toth’s handling of this rivalry (with Scott behaving stoically and ambiguously throughout while Knox is visibly enraged by his wife’s preference for him), there’s already a shock when Scott offers to buy Knox’s ranch and Leslie agrees to leave town with Knox, fleeing his arrest for several murders. This scene suddenly reverses the positions of all three characters in relation to one another, which provokes Knox into declaring to Scott, “We both win,” just before we see Knox being shot on the staircase.

But when I looked up the entry for this movie in the American Film Institute’s online film catalogue, I

discovered the following: In the preface to director Andre De Toth’s autobiography, French director Bertrand Tavernier mentions a controversial ending to Man in the Saddle, in which the character played by Randolph Scott, Owen Merritt, repeatedly shoots Alexander Knox’s character, Will Isham.

Tavernier stated that Scott was reluctant to do the scene. However, there is no indication in the

film’s production file, or the file on the film in the MPAA/PCA Collection at the AMPAS Library, that a second ending was filmed. It is likely that Tavernier confused the ending with the scene

in which Isham kills Hugh Clagg [John Russell].

Once I looked at the film again, it became clear that the AFI hypothesis was not only likely but certain. Clagg is every bit as consumed with sexual jealousy and murderous rage as Isham is, although the woman he’s obsessed with isn’t Isham’s wife but her best friend, Nan Melotte (Ellen Drew). The murder in question occurs just after a protracted fistfight between Merritt and Clagg—a tour de force in its own right — that starts inside a cabin where Clagg has tracked down Melotte and Merritt and where their body blows cause the cabin’s roof to collapse before they tumble down a steep hill beside a waterfall. (Melotte tumbles after them.) Clagg then escapes on his horse and rides back to Isham. As he recounts finding Merritt with a woman whom he describes as a despicable cheat, Isham, assuming that he must be referring to his wife, shoots him three times for insulting her.

I’ve gone into so much detail about this grisly and shocking murder and Tavernier’s faulty memory of it in order to suggest that de Toth’s relative detachment from genre conventions creates a certain smokescreen, entailing positive as well as negative results — freshness and a lack of sentimentality on the one hand and confusion begetting more confusion on the other. The fact that Tavernier could misremember a villain killing a secondary character as a hero killing a villain implies an overall focus on specific effects rather than on specific characters or plot points. Like the 3-D effects of objects being flung at the viewer in The Man in the Saddle, he likes to produce jolts as if they were pranks. That’s why

Tavernier’s observation proves to be right even when it’s wrong, because it’s the jolt rather than the characters that we remember.

.

Consequently, the overall dramaturgy of Man in the Saddle is too peculiar and abstract to “work” in any ordinary fashion because de Toth seems to be standing in an oblique relation to all his characters, refusing to judge or even understand any of them conventionally. Experienced musically and formally, Isham’s protracted murder of Clagg is a recap or extension of Clegg’s protracted fistfight with Merritt, an effect that’s intensified by the sexual jealousy motivating both forms of violence. This may account for the fact that few of de Toth’s films end with a satisfying feeling of closure, because their usual tendency is to open things up, not close them down.