Claude Chabrol died at the age of eighty, and I’d like to celebrate his work by focusing on what I regard as probably the greatest and most masterful of his later films, made in 1995 but released in the U.S. two years later. This review, which was later used on the film’s American DVD, ran in the Chicago Reader on February 14, 1997; it’s reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema, my most popular book on Amazon. — J.R.

The Ceremony

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Claude Chabrol

Written by Chabrol and Caroline Eliacheff

With Sandrine Bonnaire, Isabelle Huppert, Jacqueline Bisset, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Virginie Ledoyen, and Valentin Merlet.

It’s odd that Claude Chabrol is the most neglected filmmaker of the French New Wave today, at least in this country, because he started out as the most commercial and has turned out to be the most prolific, with the possible exception of Jean-Luc Godard. I’ve seen 33 of his 46 features, but nothing in over a quarter of a century that’s quite as good as La cérémonie, an adaptation of Ruth Rendell’s novel A Judgement in Stone.

Born in 1930, about six months ahead of Godard, Chabrol came from a family of pharmacists (as did Jacques Rivette). At the age of 17 he met François Truffaut at a screening of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, and ten years later he collaborated with Eric Rohmer on the first critical study of Hitchcock to appear anywhere. For four years in between he regularly wrote for Cahiers du Cinéma — less memorably than Godard, Rivette, Truffaut, or Rohmer — under his own name as well as the pen names Charles Eitel and Jean-Yves Goute. In 1955 he worked as head publicist at 20th Century-Fox’s Paris office. Like Truffaut, he financed his first feature by marrying into money. He also coproduced key early films by Rivette and Rohmer and served as technical adviser on Godard’s Breathless.

His best films have tended to come in clusters. His two richest periods were 1958 to 1961 (his first six features: Le beau Serge, The Cousins, Les bonnes femmes, À double tour, Les godelureaux, Ophélia) and 1968 to ’70 (La femme infidèle, Le boucher, This Man Must Die, Just Before Nightfall, and, a cut below, La rupture). The worst film of his that I’ve seen — and there are many contenders, for he’s done a lot of hackwork — is The Blood of Others (1983), a film in English about the German occupation of France done for American cable.

The plot of The Ceremony is fairly simple, but it’s also full of ambiguity — something that corresponds at times to the elegant mise en scène. The very first shot, for example, follows Sophie Bonhomme (Sandrine Bonnaire) as she crosses the street toward the camera, turns to the left, enters a café, and is greeted by Catherine Lelièvre (Jacqueline Bisset), who calls her over. It’s a shot lasting over half a minute, and something of a tour de force, because it involves several camera movements and a continuity between exterior and interior lighting. What makes it ambiguous is that it seems like an objective shot filmed from the approximate vantage point of Catherine, who’s sitting inside the cafe watching Sophie approach through the plate-glass window. It isn’t until the shot is more than half over that we glimpse Catherine in the foreground and realize that what we’re seeing is subjective.

Catherine is an upper-class woman living in Brittany with her husband, Georges (Jean-Pierre Cassel), her son, Gilles (Valentin Merlet), and her stepdaughter, Melinda (Virginie Ledoyen, star of the recent A Single Girl). Catherine is looking for a maid, and Sophie has come for an interview. In this precredits encounter both women seem serious and reasonable. Catherine, who insists on ordering tea for Sophie, explains that her house is large and ten kilometers away and that she manages an art gallery. Sophie presents her letter of reference, and they arrange for her to start in three days, settling on a salary slightly higher than Sophie’s previous one.

The standard critical line about Chabrol is that he’s a Hitchcockian, with a mise en scène periodically grounded in subjective camera angles. I can’t deny this facet of his work, but an equally important influence, by Chabrol’s own testimony, is Fritz Lang, whose hallmark as a filmmaker is a certain abstract objectivity, and it is in the play between Hitchcock’s subjectivity and Lang’s objectivity that Chabrol’s best work usually takes shape.

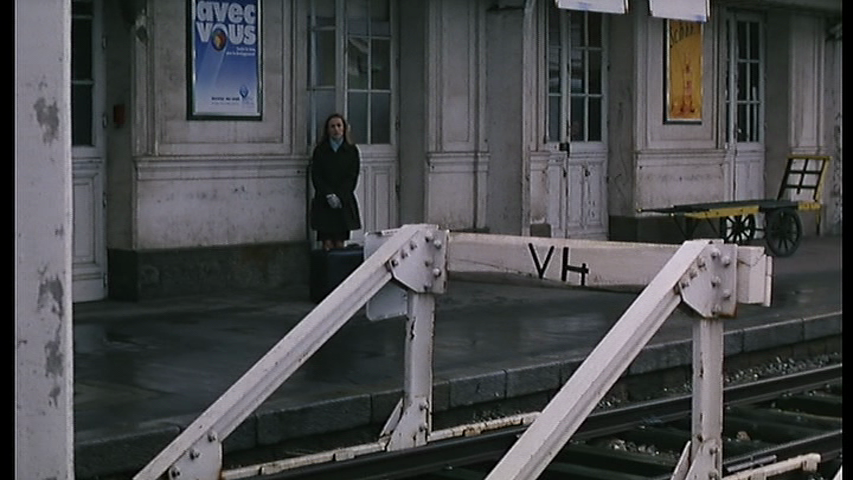

Just as the first shot in the film is a Hitchcock shot that begins by masquerading as a Lang shot, there’s an apparently Langian continuity cut that introduces the second encounter between Catherine and Sophie — a cut from a line of dialogue stating that Sophie will be arriving on the train at 9 AM to Catherine on the train platform at 9 AM, looking for Sophie without finding her. (A “Langian continuity cut” of this kind is one that literalizes a line of the dialogue in the following image, such as the cut in Lang’s The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse from a character saying that the weather isn’t fit for a dog to a shot of a dog in the bad weather.) But then comes a subjective pan following Catherine’s gaze as she spots Sophie on the other side of the tracks — an eerie play on expectations that qualifies as Hitchcockian.

“The savage derider of the bourgeoisie has become its elegiac poet,” critic Robin Wood wrote of Chabrol in 1970, in the first and perhaps only book written about him. But it might be argued that a furious love-hate response to his own class has been part of Chabrol’s work from the beginning and surfaces here in less apparent ways. It’s the kind of ambivalence that could probably be traced back to Balzac, but more contemporary and perhaps more pertinent references would be the class tensions and resentments found in the thrillers of James M. Cain. Like Cain (and to a lesser extent early John O’Hara), Chabrol sees his bourgeois characters as insects trapped in spiders’ webs; he both sympathizes with their plight and regards them as pathetic. Sometimes this has a subversive edge — if memory serves, the neglected Just Before Nightfall (1970) makes a strong moral argument on behalf of murder. Yet the political meaning of Chabrol’s relation to the bourgeoisie is still being debated. In one of his uncollected and untranslated “mythologies” (a series of magazine articles written over several years in the 50s) Roland Barthes attacks Chabrol’s first feature, Le beau Serge, for the right-wing aspects of its “microrealism,” its static view of human nature.

The Ceremony marks an important shift in Chabrol’s view of the bourgeoisie; for the first time he seems to like his bourgeois characters without irony or sarcasm: they’re a sweet bunch of people. Yet most of The Ceremony is seen from the vantage point of Sophie and her best friend, Jeanne (Isabelle Huppert), a postal worker whose hatred for the Lelièvre family grows to such unreasonable proportions that anything becomes possible. The brilliance of Chabrol’s movie rests precisely in this dialectical ambivalence: one feels throughout that he has nothing but affection for the Lelièvres, yet he also understands deeply the murderous class hatred of Sophie and Jeanne and precisely how it develops. Like the ambiguous shifts between a Hitchcockian and a Langian approach, this ambivalence gives Chabrol’s thriller most of its tension and edge. Significantly, his cowriter — Caroline Eliacheff, the wife of Marin Karmitz, the producer — is a psychoanalyst, and in interviews Chabrol credits her for developing the psychology and psychopathology of both these women beyond the elements found in the novel. (Readers who don’t want more of the plot revealed should check out here.)

Perhaps the key delayed revelation in the film is the fact that Sophie is illiterate — a carefully guarded secret that accounts for much of her previously inexplicable behavior. Presumably this isn’t a fact that’s kept from the reader of Rendell’s novel, which is titled L’analphabète (“The Illiterate”) in French, so I would guess that Chabrol uses it because he wants to establish reasons for Sophie’s alienation from the Lelièvre family without telling us what those reasons are — as a way of keeping us curious about the character and transfixed by her behavior. (Her relationship to the TV in her room is especially suggestive in this regard; indeed, both TVs in the house prove as important to the plot as any of the family members.) It’s Jeanne who wears her class animosity and her particular hatred of the Lelièvres on her sleeve, and who appears much more aggressive and rebellious than Sophie. But it’s Sophie who takes control when the two finally slaughter the entire family.

Ultimately the folie a deux of Sophie and Jeanne — their collectively generated madness — becomes the focus of our stunned curiosity, and it’s part of Chabrol’s considerable achievement to make us follow the horrifying logic of their behavior even when we can’t fully understand it. (We may be reminded of the two lead characters in Jean Genet’s one-act play The Maids — or of the notorious Papin sisters, who murdered their employers in the 1930s, one of Genet’s inspirations and reportedly one of Eliacheff’s reference points as well.) Is there an unrealized erotic element in their friendship that can ultimately find expression only in violence? And what about Sophie’s responsibility in the death of her father and Jeanne’s in the death of her young daughter, two mysteries that Chabrol prefers to leave open? (According to an interview he gave in Positif last year, Chabrol and the two lead actresses decided that Sophie’s father’s death was deliberate and Jeanne’s daughter’s death was accidental, but there’s nothing in the movie that allows us to arrive at these conclusions with any confidence.)

All we can really conclude is that together Jeanne and Sophie become a lethal pair, though separate they would probably have remained harmless. Taking the same principle further, these two murderers and these four bourgeois family members form a single complex organism that eventually turns on itself. Chabrol’s heart may be more with the family, but he still understands their assassins with remarkable clarity, and The Ceremony pivots on the mystery of that understanding, a mystery contained in the Langian abstraction of the film’s title. As Jeanne says to Sophie after they’ve completed their bloody work, “On a bien fait” (“We have done well”), a creepy line that’s part of the plot’s final twist — and a boast that Chabrol can make to his coworkers with equal justice.