This originally appeared in the May 23, 1997 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

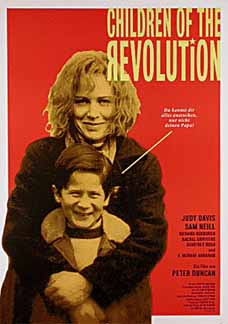

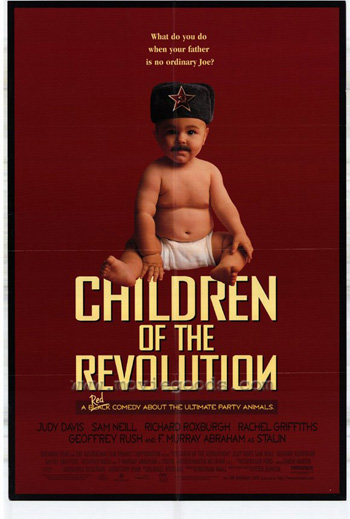

Children of the Revolution

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Peter Duncan

With Judy Davis, Sam Neill, F. Murray Abraham, Richard Roxburgh, Rachel Griffiths, Geoffrey Rush, Russell Kiefel, John Gaden, Ben McIvor, Marshall Napier, Ken Radley, Fiona Press, and Alex Menglet.

This cockeyed story is recounted by several narrators in pseudodocumentary style (a style distantly patterned on Warren Beatty’s in Reds): various old codgers in present-day Australia speak to the camera about the past, their accounts leading into several extended flashbacks. Judy Davis plays Joan Fraser, a red-diaper baby who learned about Karl Marx from her father when he took her fishing. In 1949 — during the darkest days of the cold war — she’s a young woman who still dreams of a workers’ revolution and still idolizes Joseph Stalin. When Prime Minister Robert Gordon Menzies decides that Australia should follow the U.S. into Korea and outlaw communism and sign various anticommunist treaties, Fraser goes ballistic: she gets herself and her boyfriend, Welch (Shine’s Geoffrey Rush), ejected from a movie theater by causing a commotion during a newsreel, decides it would be OK to go to prison (“What do you people want — a discreet revolution?”), proposes a march on the parliament, and speaks to workers. She also sends a steady stream of passionate letters to Stalin; Welch — a cabinetmaker who’s smitten with her rather than her politics and wants to marry her — can’t capture her interest.

One day Fraser gets a visit from David Hoyle (Sam Neill), apparently an Australian spy who’s intercepted one of her letters to Stalin, and he gives her a friendly warning. She visits the Soviet Union in 1953 — after Stalin (F. Murray Abraham) happens on a file of her letters and invites her to come — a complex journey traced by a succession of red stars on a map. Hoyle, apparently now working as a spy for the Russians, follows her. Fraser attends a banquet and a midnight screening of a Hollywood movie with Stalin (we hear Satchmo singing “Just One of Those Things” as Stalin puts his arm around her); later we see her come out of Stalin’s bedroom looking distraught. Learning later that Stalin has just died, she swears she doesn’t recall what happened the previous night. Hoyle comforts her, and she appears to wind up in bed with him as well.

Back in Australia, Fraser pretends she never met Stalin but announces to her boyfriend that she’s pregnant and wants him to marry her; Welch agrees on the condition that the child isn’t told he’s not the father. It’s a boy, and Fraser naturally names him Joe–a kid (Ben McIvor) who, under his mother’s tutelage, grows up to become a radical activist (Richard Roxburgh) who happens to resemble Stalin; after a stint in prison he becomes a prominent labor organizer. When Hoyle turns up wanting to know who Joe’s real father is, Fraser remains vague about what happened that night in Russia. To complicate matters further, Hoyle discovers that Joe has fallen in love with Hoyle’s illegitimate daughter, Anna (Rachel Griffiths), a Latvian emigre and policewoman who repeatedly arrests Joe as a subversive and whom Joe eventually marries.

This is a far from complete account of a movie I’ve seen only once, but I’m more interested in the forest than the trees. Much as I enjoyed the comedy of many of the particulars, the main appeal was the dreamlike allegory of the overall narrative sweep — specifically in relation to an Australian myth of origins — which may be why the story becomes less focused and resonant the closer it moves to the present.

In making some sense of this fresh and provocative movie, it may help to know that writer-director Peter Duncan’s grandfather was a card-carrying Australian communist in the 40s who adhered to his principles for the remainder of his life. (It’s probably also useful to bear in mind that Sam Neill, who plays Hoyle, is a New Zealander and is perceived in Australia as a foreigner.) But the most pertinent piece of information I have is an anecdote told to me by an Australian film and TV director who several years ago made a documentary about Australian Jewish Holocaust survivors. When he asked them why they’d moved to Australia, nearly all of them gave the same answer: they wanted to get as far away from where they’d been as possible.

Australia is a special kind of last frontier — a much more extreme example of what the west coast represents for easterners in the U.S. It’s a place inundated by the rest of the world — apart from a few days I once spent in Honolulu, I’ve never been anywhere that seemed more multicultural — but it’s also a society that has the difficult task of sorting out what’s indigenous and intrinsic and relevant to Australia and what’s not. At the same time it operates under the handicap of being considered remote and marginal by most of the rest of the world.

It’s within this context that I tend to regard the underrated Young Einstein, which turned up here briefly in 1989 — overhyped and confidently poised to conquer the American market — before going almost straight to video. Here’s what I wrote about it at the time: “Postmodernism with a vengeance. An Australian comedy that made some tidal waves on its home turf, this distant cousin of Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure has the charm and advantage of a genuine visual style of its own, both laconic and witty, as well as a likably dopey plot and cast of characters. Directed by, written by, coproduced by, and starring Yahoo Serious, the movie follows the adventures of a teenage Tasmanian apple farmer named Albert Einstein, who splits the atom in order to produce a beer that contains bubbles, falls in love with Marie Curie (Odile Le Clezio) and follows her to Paris, meets Charles Darwin, and invents rock ‘n’ roll in the process of draining off the atomic energy in a nuclear beer keg fashioned by the villain (John Howard). Invert the auteur’s name and you get a notion of what he’s up to — which is not exactly serious in its own right, but is at least serious from a yahoo standpoint.”

Children of the Revolution isn’t quite as goofy as Young Einstein, and Peter Duncan, for all his wit and polish, isn’t quite as aggressive or all-inclusive as Yahoo Serious (whom my capsule review did only abbreviated justice to — an apple that falls on Einstein’s head in Tasmania is supposed to make us think of Isaac Newton). But the desire to inject Australia into international mainstream history seems equally palpable in both movies — even if Duncan’s more ambitious and considered project is to look at Australian history in relation to the international mainstream as perceived through the complex legacies of the cold war. That he draws upon the expert services of three of the leading stars in his part of the world — Davis, Neill, and Rush — only enhances the mythical properties of his enterprise.

Equally impressive is Duncan’s stylish handling of decor, dialogue, narrative ellipsis, and pacing, all of which call to mind the Hollywood master Ernst Lubitsch — though his witty shorthand evocations of Stalin’s Kremlin are less tainted by cold-war platitudes than many of the details in Lubitsch’s Ninotchka. Some of the more Lubitsch-like details in this movie’s Soviet segments include a relay of government lackeys reading one of Fraser’s letters and weeping, a shot of Stalin reading a magazine called Movie Life, a delicious gag about prohibitions against smoking in the Kremlin, a line about Stalin spending days with the file of Fraser’s letters because “he wasn’t a fast reader,” his elaborate preparations for his romantic evening with her, and the fascist design of his spacious office (which much later is replicated in the office of Fraser’s son). Production designer Roger Ford, who says he was influenced by Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist, obviously deserves much of the credit for the office design, but Duncan’s Lubitsch-like grace allows him to seamlessly integrate this contribution and others into his bubbly style.

No less clever is the tweaking of American culture — I especially liked it when Fraser, after watching Gorbachev on TV, went into a tirade that ended “The devil is Ronald McDonald” — and the implication that Hoyle’s procommunist and anticommunist espionage may have amounted to the same thing, especially for those vast sectors of the world that were neither American nor Soviet. (For less powerful countries like Australia, the similarities between the Soviet Union and the U.S. — as international monoliths and bullies — may have been more important than the differences.) Again like Lubitsch, Duncan has a witty and humane perspective on personal, political, and historical events that’s largely a matter of maintaining a balanced if sympathetic distance from them.