From the Chicago Reader (August 22, 1997). — J.R.

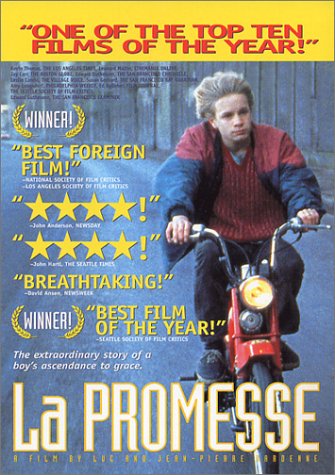

La promesse

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne

With Jérémie Renier, Olivier Gourmet, Assita Ouedraogo, Frederic Bodson, Rasmane Ouedraogo, and Hachemi Haddad.

I’d never heard of Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne before I saw La promesse (1996), an important and highly involving movie playing at the Music Box this week. But given that they’re regional filmmakers working in an unfashionable country, this isn’t surprising. Based in Liege — a city in French-speaking western Belgium — the two brothers, both in their mid-40s, started out in the 70s as assistants to Belgian director and playwright Armand Gatti. They then made leftist videos about local urban and labor issues, followed by documentary films for TV about local anti-Nazi resistance, local workers’ struggles in the 60s, and a history of Polish immigration between the 30s and early 80s. In 1986 they turned to fiction, filming a play called Falsch, and their film made the rounds of a few international festivals. In 1991 they did a more experimental feature, Je pense à vous (“I’m Thinking of You”), cowritten by the distinguished New Wave screenwriter Jean Gruault, that apparently sank without a trace after playing at a few French festivals and being slaughtered by the Belgian press.

They finally made a splash with La promesse at the directors’ fortnight at Cannes last year, then at 32 other festivals, including Toronto and New York. Their favorite movies include Rossellini’s Germany, Year Zero, Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, Pialat’s L’enfance nue, Coppola’s The Conversation, Téchiné’s Thieves, Loach’s Kes, Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, Kieslowski’s The Decalogue, Straub-Huillet’s Not Reconciled, and Oshima’s Cruel Stories of Youth, and they also have kind words for Cassavetes, Kazan, Mizoguchi, and Pasolini.

La promesse (“The Promise”), shot on the outskirts of Liege in Seraing, centers on a boy of 15 named Igor (Jérémie Renier) — the son of a single parent named Roger (Olivier Gourmet), a slum landlord who rents to recently arrived immigrants, some of them illegal. (We never learn anything about Igor’s mother, but this is one of the movie’s key structuring absences.) Igor works as an apprentice at a garage and filling station whenever he isn’t called away to help his father, but he’s called away so often that he doesn’t hold the job for long. In the opening sequence he’s pumping gas for an old woman, then stealing her wallet from the front seat of her car while pretending to check her ignition; he buries the wallet after removing the cash. Then his boss shows him how to use a soldering iron, until a honk from Roger’s van calls him away.

He and his father go to pick up a fresh batch of immigrants and their belongings, including a woman from Burkina Faso (Assita Ouedraogo) and her baby son; her husband is already one of Roger’s tenants (Rasmane Ouedraogo; no relation to either Assita or director Idrissa Ouedraogo). On the way back, Roger stops at a hospital, gets out, and pushes through a long line of patients saying his son has just had an accident. Why he needs to stop at the hospital may have been clarified by a subsequent detail in the plot, but if it was I missed it. Yet this ambiguity isn’t so much a flaw as a cornerstone of the film’s method, because the way we arrive at most of the story information given above is through inference, not through a didactic laying out of plot points.

The film is easy to follow, but it doesn’t proceed by narrative spoon-feeding. It’s here that the Dardennes’ documentary background pays off. Like Rossellini, Pialat, Cassavetes, Loach, and Kieslowski, they often proceed as if they were investigative reporters, plunging into the thick of a situation and trusting us to figure out the basic facts for ourselves (including, for instance, the intricacies of laws governing Belgian immigration). At the same time, they have a compelling sense of narrative and dramatic rhythm that carries us along while we’re picking up clues. In Cahiers du Cinéma Jean-Marc Lalanne aptly notes, “Through the mastery of its narrative effects, its capacity to describe the functioning of a microcosm and to fictionalize it, La promesse almost has the attractions of a superspiffy American movie” — though when he later compares the moral testing of Igor to “a breathless action film…with a cadence as infernal as Bruce Willis in Die Hard” I part company with him.

Amidu — the husband from Burkina Faso, an illegal immigrant, unlike his wife and son — has gambled away part of the month’s rent. Roger, who doles out under-the-table jobs to illegal immigrants, puts Amidu to work on repairs in an adjacent building, planning to deduct the rent from his wages. A labor inspector is about to turn up, and Igor, who’s just lost his garage job, warns every illegal immigrant to vacate the building before he arrives. Then Amidu falls from the high scaffold he’s working on. Close to death, he asks Igor to promise to take care of his wife and child, and Igor agrees. Igor wants to take him to the hospital, but Roger, fearing reprisals by immigration authorities, hides Amidu’s body instead, and later gets Igor to help bury him under cement. It’s the second burial in the movie (the wallet was the first), and in every respect the movie’s turning point, because afterward Igor proceeds in every way he knows to honor his promise to Amidu.

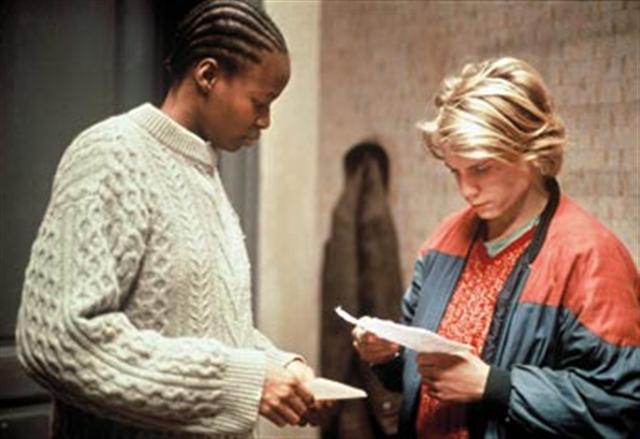

Long before Amidu’s accident we see Igor spying on Assita in their room, but whether he’s later honoring her late husband’s wish or shifting his allegiance from his father to an unlikely mother surrogate is one of the many issues the film leaves open. The complex accommodations between Igor and Assita as he both lies to her about her husband’s whereabouts and refuses to abandon her (as Roger insists he do) provide the compelling drama of the film’s second part.

In explaining Igor’s change of heart, which ultimately leads him to reject his father, the Dardennes cite an exchange between the character Marcel and his mother in Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov: “How,” asks the mother, “can you be guiltier than anyone in the eyes of all? There are murderers and brigands. What crimes have you committed to blame yourself more than everyone else?” “My dear mother, my deepest love, know that everyone is guilty in everyone’s eyes. I do not know how to explain it to you, but I feel that is so, and it torments me.”

Rightly or wrongly, the standard idea we have about most left-wing narrative art is that the storyteller has a thesis to propound and that the story shapes that thesis. But the Dardennes view Igor as mostly a mystery — as they do Assita when she picks through the entrails of a chicken or visits a seer trying to discover where her missing husband is. The filmmakers treat both characters in a matter-of-fact way, but they don’t claim to know much more about them than we do. Part of the excitement of La promesse has to do with the way they share their curiosity with us.

The drawback of this approach is that they can take their lack of knowledge only so far. For one thing, I find it impossible to imagine what transpires between Assita and Igor after the final shot, which suggests that the film ends at the precise point when its imagination reaches its limits. However, this approach does make possible a kind of comparative anthropology that combines compassion with a lack of sentimentality and allows us to discover each character in relation to the other. The Dardennes also seem to know and understand like the back of their hands the world both characters live in, including the factors that force them together and ultimately make them both pariahs. Inviting us to share this knowledge as well as their curiosity about two isolated individuals, they discover a world where conversation gradually becomes possible, not only between these two characters but between us and the film — a conversation about theses still in the making.