From the Chicago Reader (September 26, 1997). — J.R.

Medea

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Lars von Trier

Written by Carl Dreyer, Preben Thomsen, and von Trier

With Kirsten Olesen, Udo Kier, Henning Jensen, Solbjaig Hojfeldt, and Prehen Lerdorff Rye.

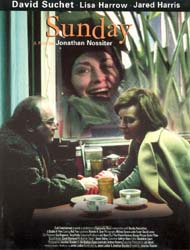

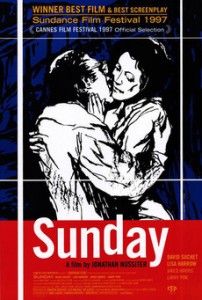

Sunday

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Jonathan Nossiter

Written by James Lasdun and Nossiter

With David Suchet, Lisa Harrow, Jared Harris, Larry Pine, and Joe Grifasi.

It’s been disconcerting to read, over the past several weeks, of no fewer than four Hollywood projects in the works that purport to be by and/or about Orson Welles. Three of these are based on Welles scripts that he never found the money to produce: The Big Brass Ring (an original with a contemporary setting), The Dreamers (an adaptation of two Isak Dinesen stories), and The Cradle Will Rock (an autobiographical script set in the 30s). Yet all have been extensively rewritten, and the fourth — as recently reported by Todd McCarthy in Daily Variety — is a series of whole-cloth inventions about the making of Citizen Kane, presumably with a few facts thrown in, called RKO 281, written by Chicago playwright John Logan.

Why is all this money, effort, and media attention being expended on “celebrating” Welles when nobody is showing the slightest interest in making available unseen Welles features like Don Quixote and The Other Side of the Wind? I suspect it’s because the prospect of a fresh, unseen Welles feature is just as threatening today as it was when he was alive. But the idea of a feature magically enhanced by the aura of Welles’s genius and executed by someone less talented is commercially irresistible.

Does this mean that when push comes to shove, the public doesn’t want to see a new Orson Welles film? I wouldn’t say so, because such a film, now as before, is an untried and untestable plunge into the unknown, and how can anyone (apart from bankers) make decisions about an unknown quantity? What it does mean is that the people who want to see a new Orson Welles film — and I happen to know quite a few — don’t have a marketable demographic profile, at least according to current industry wisdom. This same principle of visibility also means that audience members either (a) complain that there’s nothing worth seeing at the movies right now or (b) pretend that there’s L.A. Confidential, which most of my colleagues have been hawking like Wonder bread (and which I saw at Cannes and loathed for its glib, familiar cynicism). Almost no one even begins to entertain the possibility that there might be plenty of other things around — admittedly lacking massive ad campaigns and other media credentials — well worth seeing: Lars von Trier’s Medea, for instance, a video showing this weekend at Facets Multimedia, and Jonathan Nossiter’s Sunday, playing at the Music Box.

Writing in the 50s about Sacha Guitry’s Royal Affairs in Versailles, Roland Barthes noted that the use of stars enabled movies to popularize history and history to glorify and dignify movies — a trade-off enjoyed by cinephiles and historians alike: “For instance, Georges Marchal passes a little of his erotic glory over to Louis XIV, and in return, Louis XIV imparts some of his monarchical glory to Georges Marchal.” I suppose a similar sort of barter might be taking place between various Hollywood hopefuls and Orson Welles in the aforementioned projects. But I fear it will be Welles, not these bozos, who winds up with the short end of the stick. What they want from Welles, it seems, is enough of his artistic glory to dignify their own lack of ideas, but what these dim, well-financed projects are supposed to give Welles and his legacy is anyone’s guess. Accessibility? Posthumous acclamation? Thanks a lot, fellas.

Some of these thoughts were prompted by von Trier’s Medea, a video production made for Danish TV based, after a fashion, on a script written by Carl Dreyer with Preben Thomsen in the mid-60s, in the hopes that Dreyer would get the money to film it himself. The 46-page manuscript was subsequently translated into English with the help of Elsa Gress and published in a catalog for a Dreyer retrospective (which never made it to Chicago) edited by Jytte Jensen for the Museum of Modern Art in 1988 — the same year von Trier shot his version of the script in Danish. This English version is the one I’ve had access to. Gress explains in her introduction that the script is based on Euripides’ tragedy “and follows his conception of the characters in all essentials, while emphasizing the universal human features and reducing the importance of the mythical material and the specifically Greek apparatus.”

Dreyer planned to shoot his film in color in Greece, and took a special trip to Paris to meet Maria Callas, who agreed to play the lead, but no investors could be found for the project. In 1969, only a year after Dreyer’s death, Callas wound up playing the lead in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea — which took a very different approach to the same myth. To the best of my knowledge, it was her only film role.

Von Trier — a gifted filmmaker and video artist and an even more gifted bullshit artist — claimed to have been “in constant telepathic contact” with Dreyer while executing the master’s script; he also announced, apparently at the time of Medea’s Danish TV premiere, that Dreyer “has given…his approval, though not his heartfelt enthusiasm.” Even more circumspect is an opening title offering the following disclaimer: “This is not an attempt to make another ‘Dreyer film’, but rather a personal interpretation which treats the material with due respect and pays homage to a great master.”

Due respect? The Dreyer-Thomsen script dictates that the film open in “a circular arena, fenced in by a low stone wall and surrounded by green meadows,” backed by “a slope toward the sea that is not as yet visible”; it’s to be entered by a chorus “dancing with rhythmical, stylized movements to the accompaniment of recorders, string instruments, and kettledrums.” The leader is a veiled woman in black who exposes a face “which is luminous white, as white as chalk” before she delivers the opening speech, punctuated by the chorus’s lamentation.

How does von Trier “adapt” this? By eliminating the arena, the stone wall, the green meadows, the musical instruments, and the entire chorus, lamentation included, and reducing the opening lines of the soliloquy — all that he bothers to include — to a printed title. Skipping a couple of other scenes, he then provides us with an opening of his own invention: Medea (Kirsten Olesen) stretches out on the ground while the camera rises above her in an accelerating corkscrew pattern. More generally but no less crucially, Dreyer’s radical feminist take on this tragedy gets trampled under by all the distractions of von Trier’s three-ring circus; it’s certainly suggestive that while the script ends with a distant shot of Medea on a departing ship, von Trier concludes with Jason writhing in his death throes.

Is this what the Facets press notes mean by calling this Medea “faithful to the script,” claiming that von Trier “retained Dreyer’s laconic dialogue and spartan style”? I suppose I buy the laconic dialogue, but if anything ever committed to film or video by von Trier, including Medea, is spartan, then — as critic Elliott Stein once observed in a different context — “Take Me Out to the Ball Game is the memorable life story of Soren Kierkegaard.”

In fact, apart from patches of Dreyer’s dialogue, Medea is not at all like Dreyer, occasionally a bit like Ingmar Bergman, and mostly like Orson Welles — the Welles, that is, of Macbeth and Othello. I hasten to add that the two films have very different styles, starting with the studio sets and long takes of Macbeth and the disparate “found” locations and splintered montage of Othello. But von Trier, like many a postmodernist music-video maestro, never lets stylistic consistency get in the way of his stockpile of effects. Insofar as there’s any kind of dramatic logic at all, Medea is usually framed like Lady Macbeth in Macbeth and Jason (Udo Kier) like Othello in Othello.

But the moment you can forget about Dreyer — or at least reduce his contribution to some parts of the dialogue — Medea becomes an exhilarating visual feast, surpassing von Trier’s Zentropa, The Kingdom, and Breaking the Waves as an orchestration of visual enchantment. Whether von Trier is turning a speech by Creon into a Wellesian offscreen monologue to accompany a spooky trip through a dungeon; playing a game of textures with flickering shadows, fabrics, flaming torches, and naked flesh; or staging Medea’s first extended monologue in front of giant projected images of her sleeping children, there’s an undeniable Wellesian splendor to his mise en scene.

How suitable is this approach to the story of a woman who contrives to murder her own children in revenge against Jason for ditching her? It depends. Von Trier’s style here is like a lawn mower that either cuts cleanly through the material or gets stuck and creates grotesque lacerations while spinning its blades heedlessly. A flamboyant TV drama, this Medea is the reverse of Bela Tarr’s demonically single-minded Macbeth (compressed into two shots and materialist to the core), and it’s shallow and dilettantish compared to the visionary stretches of a Bergman or a Tarkovsky. Anytime von Trier can find a way to jazz up Dreyer’s simplicity, he goes for broke, substituting a pool of water for a mirror when Medea turns away from Jason, or having her hang her two children — even holding one of them up to tie the noose — instead of giving them poison on the pretext that it’s medicine.

In short, the visual effects in this Medea never quite annihilate the human drama, but they periodically overwhelm it. This makes von Trier’s video the opposite of Nossiter’s film in terms of strengths and weaknesses. The vulgar lack of inhibition that marks von Trier’s style at its best and worst is comparable to Nossiter’s compulsion to perfume Sunday, a memorably scruffy portrait of Queens and of a powerful if gritty love affair, with arty snatches of classical music, showing us how sensitive he is and thereby alienating us from the story. There’s a wonderfully purposeful discontinuity in the way Nossiter films his natural settings — sometimes the weather is quite different from one moment to the next — but whenever the setting becomes part of the story’s metaphysical structure, its stylistic “program,” it’s as clunky as the tinkling Erik Satie in the background. (At least when von Trier is pretentious, which is most of the time, he isn’t simply making the same pronouncements over and over.)

Yet Sunday has plenty of fine things to say about the everyday routines in and around a men’s homeless shelter, and even more about an impromptu one-day affair between two touching middle-aged washouts, a former IBM accountant named Oliver (David Suchet), who leaves the shelter for the day to walk around in numbed isolation, and an out-of-work English actress named Madeleine (Lisa Harrow), recently separated from her manic husband (Larry Pine), who’s carrying home to her cluttered digs a huge potted plant she found on the street.

What brings these two lost souls together is seemingly a case of mistaken identity: Madeleine addresses Oliver on the street as “Matthew Melacorta,” a famous English film director who once auditioned her for a part she didn’t get in London; Oliver decides to play along with her mistake. But as the action develops — crosscutting between Oliver and Madeleine, who proceed to a Greek diner and to her house for drinks and sex, and the men at the shelter, many of whom resent Oliver for his aloofness — illusions pile on top of illusions, and who these people are in terms of one another remains in constant flux. Oliver and Madeleine tell one another stories that may or may not be true, obscuring their real motives and identities, and eventually everything and everyone in the story figures as a free-floating metaphor for life’s uncertainties.

It’s the oldest art-movie theme in the book — illusion versus reality, masks versus identities. Nossiter dutifully pursues it almost as if no one had ever thought of it before, making Sunday generally pretentious whenever it slows down to ask us to think. Yet it’s moving, sexy, and even exalted whenever it concentrates on the sensual reality conjured up by Madeleine and Oliver — characters defined in terms of each other rather than as sociological specimens or case studies, which they also periodically become. Another way of putting this is to say that the rich, juicy performances and sheer physical presences of Suchet and Harrow periodically liberate Sunday from all the metaphysical jive, including all the moments when the film wears its style and theme on its sleeve. (Incidentally both these actors are English, but given the script’s tricky game plan, Suchet slips in and out of that identity while Harrow remains English throughout.)

Part of this triumph of meaning over style is surely Sunday‘s point, but it also suggests that, like von Trier, Nossiter is capable of making only half a terrific movie. It’s a half worth keeping.