I haven’t much cared for any of the Gaspar Noé films I’ve seen so far except for I Stand Alone, but I persist in finding this one a corrosive masterpiece. This review appeared in the July 9, 1999 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

I Stand Alone

Rating **** Masterpiece

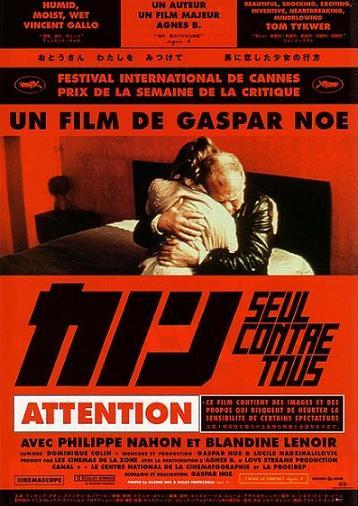

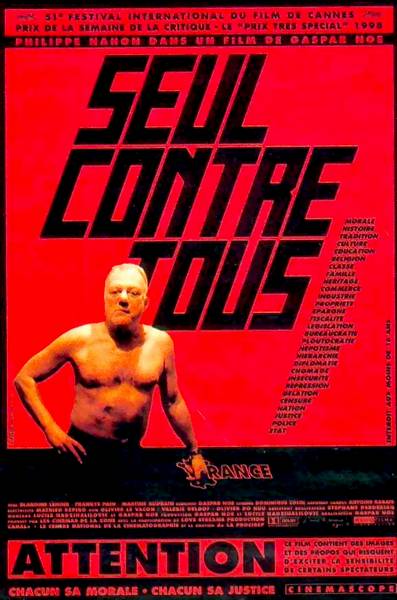

Directed and written by Gaspar Noe

With Philippe Nahon, Blandine Lenoir, Frankye Pain, Martine Audrain, and Roland Gueridon.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Gaspar Noé’s first full-length feature is a genuine shocker. It’s a sequel to his 40-minute Carne, a film that didn’t do much for me when it played the film-festival circuit in the early 90s, though I wouldn’t mind seeing it again now. This feature is called Seul contre tous, which translates literally as “alone against everybody”; I Stand Alone is cornier but rolls more easily off the tongue.

You don’t need to know anything about Carne to follow or appreciate I Stand Alone — which thoughtfully provides a precis of Carne in its opening minutes — but some familiarity with Taxi Driver or any of its spin-offs might help you experience its full wallop. Like Martin Scorsese’s film, I Stand Alone centers on an armed and enraged loner who spews macho, racist, and homophobic bile — most of which he mutters to himself –a nd is ready to mow down everyone in sight. The movie is as much inside his head as Taxi Driver was inside Travis Bickle’s, so that a great deal of what we see and think is filtered through the hero’s offscreen narration. But the differences between the films are so striking it’s difficult not to read Noé’s movie as a deconstruction of Taxi Driver — an ideological unpacking of its glamour and romance, an exposure of its lies.

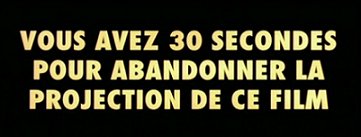

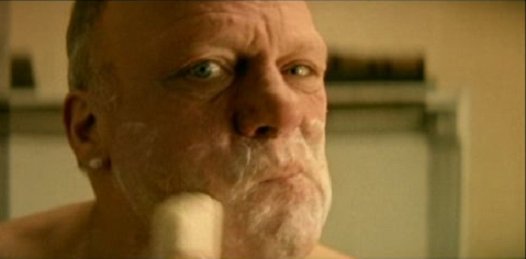

Noé gives us an unnamed French butcher in his early 50s (craggy Philippe Nahon) rather than an American cabbie in his mid-20s (lanky Robert De Niro), a series of offscreen gunshots and plucked notes to replace a swanky Bernard Herrmann score, and an exceptionally grisly urban plot about unemployment, abject violence, and incestuous delirium to replace Paul Schrader’s rhapsody about existential and excremental urban anguish. But if Scorsese’s brilliant illustration of Schrader’s script ultimately made mass murder seem sexy, Noé’s direction of his own script rubs our noses in the ugliest implications of our Pavlovian identification with his hero — and obliges us to choke on our own saliva. Movies don’t get much darker than this, because few of them have as much to say about what movies coax us into doing to ourselves.

Put more simply, I Stand Alone is a movie that removes your head, fucks with it for a while, and then hands it back to you. I wonder what the late Samuel Fuller — perhaps the filmmaker most interested in hatred and how it functions — would have made of it.

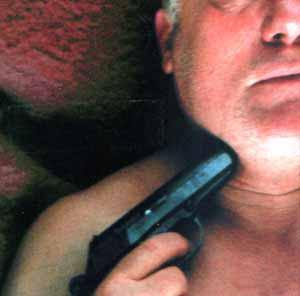

There are two very violent scenes, one near the beginning and one near the end, and women are the victims in both. Yet the feeling of violence in the movie is nearly constant, thanks to the way the narrative is constructed. Violence is present in the butcher’s stream-of-consciousness narration — most of it a torrential rant of complaint, abuse, and negativity driven by a xenophobic virulence that restores a sense of obscenity to language (no mean feat given the current climate). And it’s felt in every punctuating offscreen gunshot and plucked note, which is usually accompanied by an abrupt and jarring cut or camera movement. These percussive bursts place the butcher’s imagined violence on an equal plane with the much rarer bursts of violence we actually see and the still rarer violent acts he commits rather than imagines he commits. Every time we hear a gunshot or a sudden plucked note, our reflexes tell us that the threat of violence has just been carried out — until we realize that it’s only been imagined, by the butcher and therefore by us. By the end of the film — which offers two horrific conclusions, neither of which may be “true” — it’s apparent that our imagination and the butcher’s are not only difficult to separate from each other but virtually impossible to distinguish from the events of the story.

At the same time, the shift of camera position that often accompanies the explosive bursts gives a sense of aesthetic violence, implying that the story and our perception of it is every bit as vulnerable to Noé’s formally aggressive tactics as human flesh is vulnerable to bullets. It’s the kind of ongoing metaphor one experiences in the gut as much as in the mind, and a considerable portion of Noé’s art consists of propounding this metaphor and explaining what it means in as many ways as possible. What’s being demonstrated, one might say, is the fascism of art as well as the art of fascism — the perverse ways in which Noé’s project coincides with that of his hero.

We don’t even need the butcher for this strategy to be set in motion. The movie opens with a flaming red map of France emblazoned with a giant F and plunked in the middle of the ‘Scope frame, followed by the word “morality” and then the word “justice” filling the screen. (Rumor has it that Noé originally wanted to call this movie France.) Then we see a man pontificating in a bar, saying, “Do you know what morality is?” and brandishing his gun by way of an answer: “Here is my justice.”

Only after this do we get the credits, then the butcher offers his own bio in third person over a series of snapshots. Born near Paris in 1939, abandoned by his mother two years later. Discovers at six that his father was a French communist killed in a German death camp. Learns his trade at 14, sets up shop in Aubervilliers at 30, selling horse meat. Two years later he screws a virgin at the Hotel of the Future, across the street from the factory where she works. Nine months later a girl named Cynthia is born, and the mother abandons her and the butcher soon afterward.

Cynthia grows up mute and apparently retarded, and her father becomes sexually attracted to her when she reaches puberty. When her first period starts, she heads for her father’s shop; en route a worker tries to seduce her, but a neighbor intervenes. Spotting blood on her skirt, the butcher assumes she’s been raped, runs out in a blind rage, and stabs an innocent worker in the face. He winds up in jail, and Cynthia is placed in an institution.

By the time he gets out of jail, the butcher has lost his shop. He goes to work at a bar, becoming the matron’s lover and getting her pregnant. She proposes selling the bar, moving with him to her mother’s flat in a Lille suburb, and leasing a meat market. He accepts, but after she fails to lease a market, he grows rancorous and frustrated, especially after he’s fired from a job at a deli because he refuses to smile. (It’s now early 1980, when the remainder of the story takes place, and the film shifts from past to present tense.)

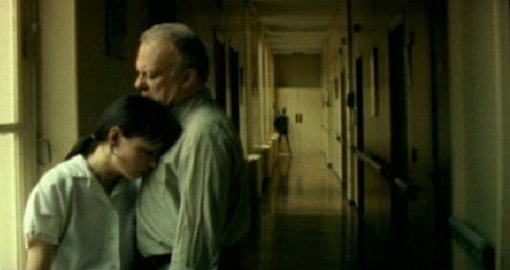

Still somewhat guilt ridden about abandoning his daughter, he works as a night watchman at a rest home, and one night is summoned by a nurse who reminds him of Cynthia to assist a dying woman. Soon afterward he attends a porn film, comes home late, and winds up exchanging insults with his pregnant lover until he explodes in rage and starts kicking and punching her in the stomach, causing a miscarriage — the first of the film’s two very violent scenes, and the only one presented as incontrovertibly real. The woman’s mother threatens to get a gun, and the butcher forces her to tell him where it is so he can take it with him when he leaves, hitching a ride to northern Paris.

From this point on the movie enters a realm of thematic, linguistic, and aesthetic brutality that continues more or less unabated until the end. One thing the butcher says to his battered mistress should suffice as an example: “Your baby’s hamburger meat; he lucked out not having to look at your lying face.” And by the end of the film his cascading offscreen monologue has become so frantic and conflicted an additional voice is needed to articulate it (the film also credits a narrator, Olivier Doran).

Just about the only verifiable events that we witness are the butcher looking despondently for work, hunting up a few old friends, nursing a few grudges, spending most of his remaining money (about $60), and finally going to see Cynthia at the institution, leaving with her, and checking into the Hotel of the Future, where the two of them wind up in the same room where she was conceived. That’s enough to make the movie feel charged with potential violence at practically every moment, because by this time the character seems sufficiently monstrous, desperate, and bitter to be capable of anything, and the violence of both his offscreen language and the offscreen gunshots has established his imagination (and ours) as being every bit as potent as anything we’ve seen.

I have no idea why Noé chose to plant his story in 1980 rather than the present. But I suspect the political climate of France during that period — when, among other things, Le Pen emerged as a political force — had something to do with his decision. The images of downtrodden humanity, the precise iconography of cruddy working-class interiors (the wallpaper and kitschy art, the dirty mirrors and naked light fixtures) — all captured as precisely and acutely as their American period equivalents in Leonard Kastle’s The Honeymoon Killers (1970) — could be found in any period in France over the past three decades, so I suspect Noé had something more specific in mind. His command of his actors, anamorphic 16-millimeter camera, sound, and editing is so awesome it’s hard to believe that any of his choices is arbitrary.

As for his moral agenda, I’m not convinced by his various pronouncements in interviews that even he has a clear understanding of what it is. I’m more inclined to go with D.H. Lawrence’s directive to trust the tale and not the teller. It’s a tale with two endings — one of them tragic, culminating in murder and suicide, and the other “happy,” culminating in sex and romance — and the movie essentially dares you to pick which one you prefer. Whichever choice you make, the movie forces you to squirm at the implications of your preference. This apparently drove one of my New York colleagues so crazy she wound up describing the second conclusion as the “most redemptive” ending in a film since Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket, a remark that startled me as much as anything in Noé’s film. For one thing, it conjures up a surrealist image of a redemption race in which all potentially redemptive films since Pickpocket leave the starting gate at the same time and only one is declared the winner. For another, it manages to postulate as comparable forms of redemption an incarcerated pickpocket’s recognition of his love for his girlfriend, expressed through the bars of his cell to the strains of Jean-Baptiste Lully, and the butcher’s rationalization of having sex with his own daughter, delivered to the strains of syrupy pseudo-Baroque music.

Admittedly, movies are open to all sorts of readings, but if this one is proposing incest as a form of redemption it must have lost me early on. That its leading character makes such a proposal, and that the film invites one to identify with him, is precisely what makes it such an infernal machine: it’s designed to tell us things about ourselves that we may not want to know. If all movies lie to us in one way or another — from the illusion of movement given by individual frames to more complex fantasies — then it might be argued that the most truthful among them are the ones that help us understand what they’re doing and what we’re doing as a consequence. This is a movie that tells me something about fascism, and then makes me pay for that knowledge.