From the Chicago Reader (June 28, 2002). — J.R.

Minority Report *** (A must-see)

Directed by Steven Spielberg

Written by Scott Frank and Jon Cohen

With Tom Cruise, Colin Farrell, Samantha Morton, Max von Sydow, Lois Smith, Peter Stormare, Tim Blake Nelson, Steve Harris, and Kathryn Morris.

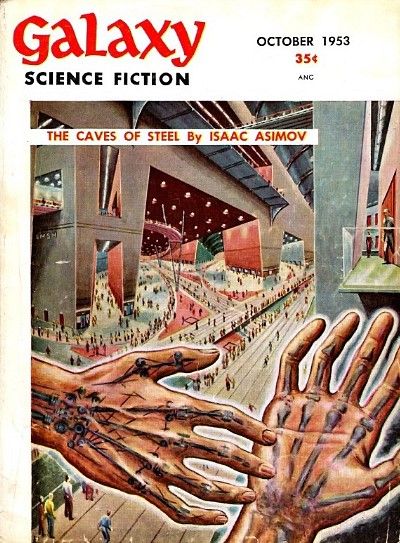

Since my early teens I’ve been stubbornly clinging to a copy of the October 1953 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction magazine, featuring the first installment of Isaac Asimov’s The Caves of Steel, a mystery story set in a vast city of the future. I prize this particular issue not for anything inside but for the cover illustration by “Emsh,” the name future filmmaker Ed Emshwiller used to sign his artwork. In the foreground two transparent hands — one revealing human bones, the other metal ones — are shown in front of the vast reaches of an enclosed cityscape with pedestrians. This encouraged me to consider not only a future city but also how it might look to both a human and a robot detective.

No story, by Asimov or anyone else, could do as much for my imagination as that Emsh cover. The only thing that came close was a single sentence by Damon Knight in his review of Asimov’s novel, which may have been what led me to the novel and that issue of Galaxy in the first place: “Asimov has turned a clear, ironic, and compassionate eye on every cranny of the City: the games children play on the moving streets; the legends that have grown up about deserted corridors; the customs and taboos in Section kitchens and men’s rooms; the very feel, smell, and texture of those steel caves in which men live and die.” This helped me imagine a future city, though unlike the Emsh cover or A.I. Artificial Intelligence, it taught me nothing about what it might be like to be a robot.

I became an SF fan because of such invitations to dream about the future, immense spaces, and one’s own origins. Early SF movies like Metropolis (1926) offered all these invitations, and their poetics were later elaborated on by films such as Blade Runner (1982), which borrowed from other diverse sources, including neonoir and Shanghai Express. Less poetic evocations of otherworldly climes, like the original Star Wars, can also create some of this magic — provided their visions are fleeting, on-screen just long enough to tease the imagination; as in soft-core-porn bubble dances, the secret is not to show too much. (The Emsh Galaxy cover may show a lot of one cityscape, but it only suggests a narrative, leaving that mainly to the viewer.)

The parallel with porn is more apparent when one reflects that most futuristic, gadget-ridden science fiction is selling something that has more to do with the present than the future: “investing in the future” is mostly about buying now, and the hype about “experiencing the future” through the latest technology is an invitation to dig into our pockets today. Maybe that’s why most SF veers more toward the right than the left — because it’s usually selling not the fancy trappings but the status quo.

Minority Report, Steven Spielberg’s enjoyable new thriller set in Washington, D.C., in 2054 — full of more alluring gadgets than you can shake a stick at — performs its own bubble dance, for good and ill. Derived from a Philip K. Dick story that’s more about action than nuanced commentary, it doesn’t have a vision that incorporates a poetics but functions as a grand entertainment; part of its central plan is to always give you more to look at than you can possibly take in. Some of my colleagues have been calling it a thinking person’s action movie, but the drive of its narrative and the heft of its visuals don’t give you much time to think — basically you’re reduced to gawking and following.

Minority Report does offer a few issues to ponder, and given the mindlessness of most summer action specials, it’s something of an intellectual feast, even if it’s all hors d’oeuvres. Yet alongside last summer’s A.I., which had the benefit of Stanley Kubrick’s intellect, Minority Report has mainly the illusion of thought. (To Spielberg’s credit, both as a filmmaker and as a thinker, he noted recently that when he saw the kind of hostile reviews A.I. was getting, he realized he must have done something right — because all of Kubrick’s own pictures since 2001: A Space Odyssey got the same sort of critical response.)

At the very least, Minority Report is crammed with details that are not so much ideas as the seeds (or sometimes the pits) of ideas. Like me, Spielberg grew up on Mad when it was still a comic book, and the hallmark of its 50s pictorial style, which he was already emulating two decades ago in 1941, is to stuff wisecracks into the edges of the frames; here he does the same thing with modules of future-think furnished by a team of experts he and his staff organized. Yet some of these modules work less as ideas than as mechanisms designed to shove us forward; the “minority report” itself, which figured significantly in the Dick story, functions here mainly as one more red herring.

***

Sustained thought is discouraged here by the characters, situations, and premises — however serviceable they are in other respects. Let’s start with the last of these: the notion of a “precrime” police bureau that predicts future murders in order to abort them. The most alluring thing about this notion is said to be the way it anticipates today’s headlines — the post-September 11 strategy whereby we give up some of our freedom and privacy in exchange for an assurance that future disasters will be averted. Since no such assurance can be given honestly, the value of losing some of our freedom and privacy remains to be demonstrated (at least to the American public, if not to those who’ve contrived to take these things away from us). The pitch behind such an exchange is actually a simplistic formula designed to give only the impression of thought.

This isn’t to say that Minority Report espouses having a special bureau to predict crimes (or disasters); in fact, it implies that there might be a price to pay for such meddling. Yet insofar as its bureau depends on the exploitation of three mutants, whose predictions can be recorded and played back like movies, its view of the future is neither utopian nor dystopian but a vaguely formulated conflation of the two. (If Spielberg as SF auteur has any single preoccupation, it’s cinema itself as an all-purpose agent, instrument, and metaphor.)

A philosophical conundrum is introduced in the film whereby people can’t necessarily be considered guilty of crimes they’re prevented from committing and free will becomes a bit like flesh in a bubble dance — now you see it, now you don’t. But the conundrum is more a ruse for keeping the story moving than a philosophical or moral proposition that’s explored with any coherence. At one point we see hundreds of “criminals” whose crimes have been aborted stashed away in a high-tech prison like corpses in a cemetery, but the movie doesn’t encourage us to think about these prisoners as people — the high-tech equipment encasing them is infinitely more interesting — any more than our government encourages us to think much about the indeterminate number of terrorist suspects it’s now detaining indefinitely. In the news, as in action movies, simple, fast-moving narratives with clearly marked good guys and bad guys are what’s needed — and slowing things down long enough to allow us to notice the extras can only be a needless distraction.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that narrative momentum — and this movie has plenty of it — ultimately serves salesmanship of one kind or another more than analysis. Of course there’s nothing necessarily wrong with this, at least in the realm of entertainment — I was as elated and as absorbed by the rush of events and images as anyone. But don’t be conned into thinking that some sort of serious, thoughtful statement is being delivered along with the roller-coaster ride.

The characters in Minority Report are more developed than the pasteboard figures in the Dick story, though only in the sense that they have more detailed back stories — all of which are unfortunately standard issue and stripped for action. Chief John Anderton (Tom Cruise, whose production company made the film) is a drug addict mourning the mysterious loss of his son six years before. This tragedy is used so glibly and mechanically to explain the end of his marriage and his interest in precrime that it isn’t so much motivation as a ploy to prevent our asking about his motives. His estranged wife, Lara (Kathryn Morris), is even less of a character. Unlike many of Asimov’s characters and the hero of A.I., these people aren’t robots, but they might as well be. (What makes Anderton “human” is his grief over his missing son and his desire for vengeance, two movie staples; otherwise he’s a zero.) That the mutants predict Anderton will commit a murder of his own adds plenty of plot interest but nothing at all to his character. To an even greater extent, Anderton’s mentor (Max von Sydow) and his antagonist from the FBI (Colin Farrell) don’t exist apart from their plot functions. This isn’t to deny that the plot is full of neat and ingenious twists, only that these stunts aren’t worth dwelling on — not only because they shouldn’t be spoiled, but also because they can’t be taken very seriously.

Character in the old-fashioned sense is distributed much more liberally to character actors in character parts: a prison guard who performs Bach (Tim Blake Nelson), a sadistic mad-scientist surgeon with an archetypally grotesque assistant (Peter Stormare and Caroline Lagerfelt), and the biggest scenery chewer of all, a greenhouse scientist named Dr. Iris Hineman (Lois Smith — the same actress, I was astonished to recall, who played a whorehouse madam’s callow young assistant in East of Eden 48 years ago), who’s accorded one scene in order to give us some vital exposition. All of these characters are colorful but so clearly labeled as such that, through no fault of the actors, they wind up having certain robotic tendencies. (They’re obviously built to serve the filmmaking and storytelling machinery, yet the fact that they’re programmed like us isn’t part of the plot or theme, as it is in A.I.)

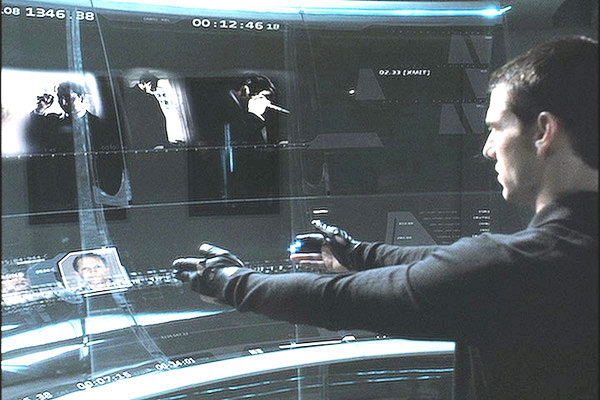

More impressive is Samantha Morton as Agatha, the most powerful of the three mutants — a religious icon clearly designed to suggest Stanley Kubrick’s Star Child in 2001 and Carl Dreyer’s Renee Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc, but also a striking figure in her own right who doesn’t depend entirely on those references. However, she — like her mutant partners, Arthur and Dashiell — is named after a classic mystery writer. (Guess who.) Her name — like the credited clip from Rouben Mamoulian’s The Mark of Zorro and the uncredited clip from Samuel Fuller’s House of Bamboo playing on the wall of the surgeon’s lair and the bits of Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony heard in the precrime bureau while Anderton or his antagonist pull together precrime clips with grandiloquent gestures — is there to provoke our recognition not of the future or even of the past, but of the media-savvy present.

It’s Spielberg’s peculiar genius that he thrives on delivering a surfeit of emotional and visceral kicks, sometimes to the point of making us feel as if we’re chasing breathlessly after a circus, and there were times — to stretch the metaphor a bit — when I wanted to concentrate more on single acts than on all three circus rings at once. As much as I enjoyed Smith’s performance, I resented her cavorting, digitally hyperactive plants — inventiveness run amok — for competing with her own grandstanding and not functioning simply as comic props. Similarly, the use of showbiz standbys can be mildly insulting: the implausible gross-out gags of a temporarily blinded Anderton scarfing down one disgusting-looking dish or drink after another from the surgeon’s moldy refrigerator evoked the money shot of dinosaur shit in Jurassic Park, making me feel that Spielberg was manipulating my responses with the same excessive, proprietary glee his honcho figures show manipulating their precrime clips.

And what about the world these characters are planted inside? It’s divided between filthy alleys and flophouses on the one hand and awesomely spiffy malls, buildings, and roadways on the other, but this division seems to derive more from set-decorating schemes than from any sort of social speculation or insight. Perhaps we’re supposed to be so impressed by the overhead camera movement tracing the paths taken by mechanical spiders through the rooms of a flophouse that we won’t notice that the flophouse has no relation to any sort of genuine destitution, past, present, or future. Like the kettledrums heard behind the opening credits, these rooms are designed to put us in a Blade Runner frame of mind — albeit a cozier one — and not to offer any commentary on the world we live in.

Blade Runner kept a sense of social observation amid all of its design references, but this movie is content to deck out its Blade Runner and various noir milieus with a lot of stray (if striking) technological details. And even if we’re meant to walk away from Minority Report with a certain skepticism about overly eager crime prevention, that doesn’t mean we’re supposed to reflect on this movie’s methods of control and coercion, as we were in A.I. Minority Report isn’t so much a statement as it is a box of toys, some of which are labeled “dark” or “thoughtful” to add to the fun.