In my original review of this documentary, I cited and recommended some writing by Eliot Weinberger that three of my editors regarded as irresponsible and unreliable and therefore something that shouldn’t be mentioned, along with some of my own pronouncements. Readers who would like to judge this matter for themselves can read my unedited draft, which I’ve added below the published version. The edited version appeared in the February 7, 2003 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

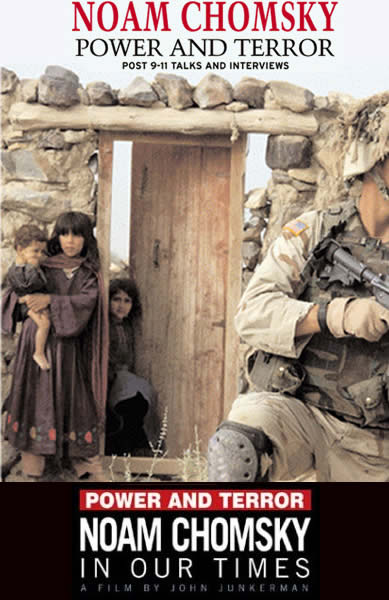

Power and Terror: Noam Chomsky in Our Times

*** (A must-see)

Directed by John Junkerman.

As a work of cinema, John Junkerman’s documentary about Noam Chomsky doesn’t set the world on fire. The film is a prosaic compilation of interview footage of the linguist and political analyst in his office at MIT intercut with footage of him speaking in Palo Alto, Berkeley, and the Bronx last spring. He’s also shown chatting with students about U.S. foreign policy, the “war on terrorism,” and representations of both in the American media. Unlike Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick’s Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media (1992), a Canadian film that’s well over twice as long, Power and Terror: Noam Chomsky in Our Times doesn’t try to offer a comprehensive portrait of its subject or a wide-ranging survey of his thought. Yet Power and Terror kept me interested for its full 74 minutes with a series of surprises. Here are four I found especially noteworthy:

(1) It’s a Japanese film — beginning and ending with and frequently accompanied by Japanese pop songs, all by Kiyoshura Imawano. (None of the songs are subtitled, though English words pop up in the lyrics intermittently.) Junkerman — an American filmmaker based in Tokyo and working with a Japanese producer and mainly Japanese crew — has focused on Japanese subjects in four of his previous half-dozen documentaries. Here the most obvious Japanese angle is an emphasis on Chomsky’s critique of the imperialist excesses of Japan, principally its cruel treatment of the Chinese. More subtle and yet more crucial is that although the on-screen audiences are American, the film addresses its American viewers as members of a global community. I can’t even imagine a member of the Bush team speaking to us in this fashion. The film offers a small taste of the sort of discourse that’s been going on lately outside the U.S. — and not only in Japan.

Junkerman declares in the film’s press book that in the early aftermath of 9/11 he was “startled to hear that some 95 percent of Americans — and 100 percent of opinion makers — had taken up the call to arms.” As a member of the dissenting 5 percent, he writes, “I felt lonely and disheartened. Had we learned nothing from 15 years of fighting a delusionary war in Vietnam? Did no one stop to question whether military force was the answer to terror?”

I share Junkerman’s sentiments, though I wonder whether the prowar consensus he describes isn’t more apparent than real. Surely the statistics he quotes are as questionable as the numbers generated by Hollywood test-marketers, whose polling methods privilege knee-jerk consumption patterns over taste, loaded questions over open-ended inquiry, and fleeting impulses over long-term convictions. (When Peter Bart, the editor of Variety, recently vented his disdain for American movie critics who develop their own, idiosyncratic ten-best lists instead of conforming to the orthodoxies and complacencies of the studios and the Oscars, it reminded me a little of Bush telling the world, “You’re either with us or against us.”)

A more genuine consensus created in the wake of 9/11 is a global one that rejects American military unilateralism. The degree to which Bush has inadvertently strengthened this sense of community outside America is made palpable, and one of the film’s most precious gifts is its invitation to Americans to join this company.

(2) Power and Terror is not the America-bashing exercise one might expect when the subject is Chomsky. In part that’s because Chomsky’s views have been more often parodied than understood — thanks in no small measure to the efforts of neoconservative critics like Norman Podhoretz and Christopher Hitchens. Here Chomsky emphasizes that imperialist powers all tend to behave in the same way, that back when the British Empire was the one on top it was no better than ours is now (his criticism of Winston Churchill is especially withering). Chomsky also takes pains to note that, for all its hypocrisy, all its slogans about the “war on terrorism” and the “axis of evil,” the Bush administration is actually far more upfront about its intentions than the intellectuals who try to rationalize its policies.

(3) The film opens with a flurry of short printed quotations about Chomsky, one of which comes from the New York Times: “Arguably the most important intellectual alive… his political writings are maddeningly simple-minded.” Initially I laughed at this as a prime example of Times doublethink, but on further reflection I realized that it’s absolutely correct. But why should we value intellectuals in proportion to the abstruseness and complexity of their ideas? Chomsky’s simplicity is really lucidity; it has nothing to do with naivete and everything to do with expediency. Chomsky cuts to the chase.

(4) The biggest surprise of all is Chomsky’s cheerfulness. His affability isn’t a mask but a sign of genuine optimism. For an American like me, who first discovered the depth, degree, and longevity of American brutality against people in South America and the Middle East through Chomsky, his work can be depressing and upsetting — especially if one accepts the received wisdom that there’s been no operative political opposition to imperialist brutality in this country since the 60s. Patiently and persuasively, Chomsky explains that appearances can be deceiving in these matters — that opposition to the war in Vietnam didn’t become effective until well into the 70s, and that feminism and environmentalism didn’t truly register until well after that. With our nation poised to initiate an invasion that would likely, according to UN estimates, cause a half-million casualties, this is no time for whistling contentedly. Still, Chomsky’s observations offer real grounds for hope that as feelings of membership in the world community spread in America, effective political opposition to military unilateralism and the concomitant slaughter of innocent civilians will grow.

At 74, Chomsky has kept abreast of concerns other intellectuals have chosen to ignore for half a century. He has no interest in downplaying the damage that we are capable of inflicting. But neither does he want to minimize the forces of dissent in this country. Most of his colleagues deem these countercurrents to be ineffectual or even invisible, but Chomsky sees them as growing steadily in power and size. And because some of us are only beginning to pick up on the damage, it’s about time we got better acquainted with the opposition. Power and Terror is a good place to start.

Postscript: The following is my original review before it was edited for publication:

Power and Terror:

Noam Chomsky in Our Times

***

Directed by John Junkerman

As a work of cinema, John Junkerman’s recent documentary about political analyst and linguist Noam Chomsky approaches a zero level of interest. Following a few of Chomsky’s speaking engagements in March 2002 as he chats with students about U.S. foreign policy, the “war on terrorism,” and the perceptions of both in U.S. media, in Palo Alto, Berkeley, and the Bronx — interlaced with portions of an interview he gave in May, in his office at MI — the film is unabashedly conventional and predictable in its format, both as hagiography and as a string of extended sound bites. Anyone who’s encountered much of Chomsky before, either through his books or in other documentaries, should find nothing here to challenge the impressions made in those appearances. Unlike, say, Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick‘s Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media (1992), a Canadian film that’s well over twice as long, Power and Terror shows little interest in offering us a comprehensive portrait of the man, much less an extended commentary. (The closest it ever comes to the former is asking Chomsky how he might relate his linguistics to his political concerns — and receiving the reply that he invariably gives to this question, that there’s very little relation.)

Yet despite all these misgivings, I have to confess I find Power and Terror: Noam Chomsky in Our Times packed with interest and full of odd surprises throughout its 74 minutes. There are many bracing anomalies I could cite, but here are four that seem particularly worthy of attention:

1. It’s a Japanese film —- beginning, ending, and frequently accompanied by Japanese pop songs, all of them by Kiyoshiro Imawano. (None of these are subtitled, though English words pop up in the lyrics from the time to time.) Junkerman — an American filmmaker based in Tokyo, working with a Japanese producer and a mainly Japanese crew — has focused in four of his previous half-dozen documentaries on Japanese subjects, and here the most obvious “Japanese” inflection of the material chiefly consists of the points in Chomsky’s discussions when the imperialist excesses and cruelties of the Japanese, principally against the Chinese, are singled out for criticism. It’s also evident in the fact that, despite the fact that virtually all the audience members we see are American, the film addresses “us” not as Americans but as members of a larger community. This might appear to be a small distinction, but actually it’s a crucial one; one can’t even imagine a member of the Bush team addressing Americans in this fashion. So one might say that this film offers a small taste of the kind of discourse predicated on an audience of world citizens that has been going on lately outside the U.S., and not only in Japan.

The degree to which Bush has inadvertently strengthened this sense of community outside America is palpable, and one of this film’s most precious gifts is to include Americans in this company. Junkerman notes in the film’s pressbook that after September 11, “I was startled to hear that some 95 percent of Americans —- and 100 percent of opinion-makers — had taken up the call to arms. As a member of that minuscule 5 percent, I felt lonely and disheartened. Had we learned nothing from 15 years of fighting a delusionary war in Vietnam? Did no one stop to question whether military force was the answer to terror?”

In response to this, I would contend that, contrary to what we’ve all heard about those percentages, they’re not very plausible, and belong with the same sort of inflated figures nurtured by the self-serving and self-fulfilling prophecies of Hollywood test-marketing and its privileging of knee-jerk consumption patterns over thought —- an attitude that confuses advertising dollars with public opinion, loaded questions with disinterested answers, and fleeting impulses with long-term convictions. When Peter Bart, the editor of Variety, recently expressed his horror at American film critics coming up with diverse favorites on their ten-best lists rather than expressing unanimity with the studios, the Oscars, and each other, he reminded me of Bush declaring that anyone who didn’t support American actions was automatically an enemy. Apparently, when it comes to either Star Wars or Star Wars there are no half measures.

2. As the above point suggests, this film is not the exercise in America-bashing that one might expect from Chomsky, based on his positions —- or at least on his positions as they’re parodically represented by such neo-conservative critics as Norman Podhoretz and Christopher Hitchens (a much more recent convert). He repeatedly acknowledges that empires and imperialist powers all tend to behave the same way, that the British Empire was no better than ours when they were the ones on top. (He’s especially withering about the behavior and stated positions of Winston Churchill.) He also takes care to point out that, in spite of the hypocrisies and double-think employed by the Bush team when they resort to their favorite mind-skipping slogans, like “war on terrorism” and “axis of evil,” that they’re much more upfront about their intentions than the intellectuals who try to rationalize their policies.

3. The film opens with a flurry of short printed quotations about Chomsky, one of which comes from the New York Times and reads, “Arguably the most important intellectual alive…his political writings are maddeningly simple-minded.” Initially this made me laugh as a prime example of Times double-think, but further reflection led me to realize it’s absolutely correct. Why should we necessarily value intellectuals according to how abstruse and complex they are? Chomsky’s lucidity and simplicity has nothing to do with naïveté and everything to do with expediency; to revert to a Hollywood analogy again, he cuts to the chase.

Chomsky isn’t the only writer and thinker capable of doing this. Check out two recent blistering and informative essays by Eliot Weinberger, “New York: One Year After” and “New York: Sixteen Months After” (both available at www.makethemaccountable.com, and slated for publication in March as a book, 9/12) if you’d like to get a cogent idea of what our government’s been up to lately, delivered with more rhetorical invective and wit than Chomsky, a relative plain speaker, seems interested in employing. Like some of Chomsky’s research, Weinberger’s findings stem in part from plans and strategies that Rumsfeld and Cheney had already mapped out on paper a year before September 11 in a lengthy document entitled Rebuilding America’s Defences: Strategies, Forces and Resources For a New Century, which is already recommending “pre-emptive strikes” with particular reference to Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, and even discussing the possibility of “some catastrophic event,” a “new Pearl Harbor,” that would facilitate its prefigured unilateral strikes.

4. Given the apocalyptic ring of Weinberger’s chilling conclusions, the biggest surprise of all in this film is how cheerful and optimistic Chomsky is. His affability isn’t a mask but a sign of what he genuinely finds encouraging. For an American like myself who discovered for the first time through Chomsky the extent, degree, and longevity of American brutality against people in South America and the Middle East, the impact can be profoundly upsetting and depressing — especially if one concludes, as I often have, with the received wisdom that no significant political opposition to this brutality has been operative in this country since the 60s. Patiently and persuasively, Chomsky explains in copious detail why this supposition isn’t true —- how opposition to the war in Vietnam didn’t even start to become effective before well into the 70s, and how, for example, feminism and concern for the environment didn’t truly register until well after that. One might easily extrapolate from his argument that the only reason why Bush hasn’t by now already started his aerial assault on Iraq, followed by an invasion with half a million anticipated casualties (according to United Nations estimates) — why he bothered to go to the United Nations after scoffing at the very notion of another weapons inspection (and has scoffed some more ever since the inspection got underway) —- is the strong American opposition to a unilateral war. This is an opposition that we and our overseas neighbors like Jukerman keep hearing isn’t supposed to exist — and an implied membership in the world community that continues to grow, however unwilling Bush seems to be about acknowledging it directly.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that we won’t be slaughtering innocent Iraqi citizens just the same —- so what’s there to be cheerful about? Let’s call it the long view. Chomsky at 74, who’s been keeping up with most of what other American intellectuals have been ignoring for the past half century, still isn’t interested in minimizing the damage this country is capable of inflicting. But he also doesn’t want to minimize the size and the force of the dissent that most of his colleagues find either invisible or ineffectual, and which he perceives has been steadily growing in power as well as size. And since some of us are only beginning to pick up on the damage, it’s about time we start getting better acquainted with the opposition. Power and Terror: Noam Chomsky in Our Times is a good place to start.