From the Chicago Reader (June 13, 2003). — J.R.

Capturing the Friedmans

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Andrew Jarecki.

It’s disconcerting to be appalled and even slightly nauseated by a masterpiece. But Andrew Jarecki’s Capturing the Friedmans is a documentary, and so it’s disconcerting largely because of its subject matter — it shocks us with the truth.

Yet if Capturing the Friedmans were less shapely and less of a masterpiece, I’d find it less troubling. Both times I’ve seen it I’ve felt that by the end practically everyone associated with the film seems tarnished in one way or another: the ostensible subjects (the Friedmans, an upper-middle-class Jewish family in the Long Island town of Great Neck), the members of their community who helped destroy much of their lives, the filmmakers, and the audience. We’re all tainted by the graphic exposure of family wounds, diminished by what we think and feel — and by what we don’t think and don’t feel. Frankly, I’m not sure whether the film deserves to be applauded or attacked for this.

The film’s story, most of which transpires over a dozen years, begins on Thanksgiving in 1987. Arnold Friedman — a highly respected and popular middle-aged schoolteacher who gives piano and computer lessons at home, and who, as Arnito Rey, led a mambo band in the late 40s and early 50s — is arrested for possessing child pornography and subsequently charged with sexually assaulting dozens of his former computer students. Many of the film’s subsequent revelations are as carefully positioned as they would be in a mystery novel or Hollywood thriller, and I feel both reluctant to give away any of the surprises and ashamed about my reluctance — because these are real lives and real tragedies that are being exposed for our entertainment and edification. (I felt just as queasy when Terry Zwigoff, the director of the masterful 1994 documentary Crumb, asked reviewers not to “give away” the information that cartoonist Robert Crumb’s older brother committed suicide after being interviewed for the film.)

I can at least say that Friedman, who privately owned up to pedophiliac urges but initially pleaded not guilty to any assaults, wound up going to prison for the remainder of his life; that his wife divorced him, while his three sons continued to defend him; and that his youngest son, Jesse, who helped his father give computer lessons, went to prison at age 19 for sexual assault (he too initially pleaded not guilty) and served 13 years. The film’s final scene shows his mother, Elaine, who has since remarried and moved, greeting him at her door for the first time after his release.

We may ask why she allowed Jarecki to record such an intimate moment, but by this point he’s already shown so many other, no less private family scenes that the question seems moot. A far more important issue is our readiness to be entertained by such events as if they were part of a Hollywood movie — which Jarecki capitalizes on and which most of the Friedmans, who seem compelled to record their lives on film and video, encourage. Still, we come away with several unanswered or half-answered questions, which is entirely to the film’s credit — especially because the apparently peripheral issue of how and why so much of this story took place in front of cameras winds up seeming like the central one. For even though we’re often persuaded to take these home movies and videos as neutral pieces of evidence, the Friedmans’ (and our) implicit trust in cameras inflects their behavior as well as the way we respond to it. The very first thing we see in the film is Jesse jokily introducing Arnold much as a TV interviewer would.

Of course if it weren’t for the Friedmans’ compulsive self-recording and our eagerness to eavesdrop, a film like Capturing the Friedmans couldn’t exist. But even if we accept this complicity as a necessary evil, the degree to which the projected scenarios of other participants affect the proceedings is formidable — the cops who elicited countless testimonies of sexual assaults and then brought charges, the defense lawyers who helped convict both father and son. And we may wind up concluding that the complicity between performers and audience isn’t simply between the Friedmans and us.

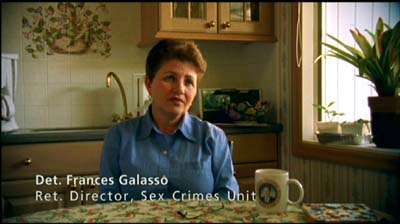

As an investigation into the psychology and processes of witch-hunts, Capturing the Friedmans is one of the most valuable film documents we’ve had since Carl Dreyer’s 1943 Day of Wrath. It shows how the feverish imaginings provoked by the very idea of child porn can create and perpetuate community hysteria. (Investigative journalist Debbie Nathan, interviewed at length, is especially illuminating on this subject.) And like Dreyer’s film — which it resembles in few other respects — Jarecki’s documentary probes most deeply into this psychopathology by intermittently asking us to share it. Rather than treat the postal inspector and the sex-crimes detectives he interviews as sitting ducks, Jarecki encourages us to share their viewpoints before gradually exposing some of their more questionable assumptions and methods. Many of the alleged abuse victims reenrolled in the computer course, and none of them reported the abuse at the time, which may raise questions about the charges filed. Yet whenever we start thinking we know precisely what did or didn’t happen the film shakes our confidence. The point, in any case, isn’t to sketch a neat diagram of victims and victimizers — which isn’t the agenda of Dreyer’s film either — but to chart some of the complex and shifting relationships between all of the characters in this excruciating drama.

The comparisons some reviewers have been making between Capturing the Friedmans and Rashomon are pertinent, though Akira Kurosawa’s adaptation of Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s “In a Grove” simplifies and dilutes its source. Kurosawa’s movie juxtaposes contradictory accounts of the same crime in order to suggest that everyone lies, but Akutagawa comes close to suggesting the more radical premise that all of his characters are telling the truth. In both the story and the film everyone possesses his or her own version of the crime. In Jarecki’s documentary we’re confronted with a more lifelike dilemma, since many of the participants are as puzzled about the ultimate truth as we are — including whether any crimes were actually committed.

Even the decision of Seth Friedman, the middle son, not to be interviewed for the film takes on a certain suggestive meaning — though that meaning, whatever it is, is deliberately minimized because Jarecki doesn’t tell us Seth refused to be interviewed until shortly before the movie ends. At another exceptional moment Elaine, in the midst of an ugly family argument, says to her oldest son, David, “Please don’t film me.” We may feel a sudden rush of sympathy for her and her uncharacteristic request for privacy — even as we recognize that her oft expressed feelings of exclusion from the male family circle are connected to her lack of interest in performing for the camera.

It’s surely no coincidence that David, apparently the most candid (and compulsive) recorder of family moments, works professionally as a clown at children’s birthday parties. (He’s reportedly the most successful birthday clown in New York City, and Jarecki’s encounter with him on his turf indirectly led to this documentary.) Performance of one kind or another seems both a symptom of this family’s complex misery and a form of treatment for it — which gives a sharp edge to the film’s narrative. (At one point David says, “Maybe I started making the videotape so I wouldn’t have to remember it myself.”) The pop songs behind the opening and closing credits — the country-western “Act Naturally,” which begins, “They’re gonna put me in the movies,” and “Jazzbo Mambo” — underscore this point. By the end we may conclude that what started out as a shared tool of denial — a kind of jocular cover-up for the father’s inexpressible turmoil — has served at least two of his sons as an ongoing therapeutic tool.

I’ve been haunted after both my viewings of the film by the establishing shots (often accompanied by music) that enhance the masterful storytelling — introducing us to Great Neck, the Friedman family residence, the Nassau County court building, the office of Jesse’s defense lawyer, all in a classic Hollywood manner. Sometimes these shots encourage certain platitudes; an early crane up the length of a tree to the sky or subsequent aerial shots sweeping across the landscape are apt to prompt us to sentimentalize the proceedings more than analyze them. These handy pirouettes are offered in much the same spirit as a later recap of “treasured moments” from home movies with gushy mood music churning behind them, which are intended to conjure up sad and tender recollections of former family happiness, complete with ironic undertones and the obligatory freeze-frame.

I can’t stop wondering whether these passages of visual rhetoric constitute building blocks of documentary or fiction, especially because so many other incidental shots or details are used in the same way, often to bolster arguments interviewees are making. After the postal inspector describes how he disguised himself as a mailman delivering porn to the Friedman house, then returned an hour later with a search warrant, we hear the offscreen sound of snapshots being taken to “illustrate” the subsequent search.

At one point we’re told that Arnold’s last-minute decision to plead guilty to more than 40 assault charges was made in an empty jury room while he was quarreling with his family, and we’re shown an empty jury room and simultaneously hear sounds of quarreling. We’re evidently being asked to accept what we hear as the actual quarrel that occurred in that room, but what if what we’re hearing is a quarrel that was recorded at another time? Does that make any ethical difference, especially given that the words aren’t very distinct? Maybe not, but if it’s trickery it’s troubling — particularly because the sex-crimes detectives did something similar when gathering some of their evidence, dropping suggestions about what might have happened, then asking others to fill in the blanks.

And what about the footage of Jesse horsing around in the court building’s parking lot with David just before his own verdict is reached — which is cited by the cops as evidence of his lack of remorse for his crimes, but which we may well see as letting off steam because he’s being railroaded into prison for crimes he didn’t commit? The fact remains that our fears and biases about forbidden kinds of sex dictate much of what we see and more of what we assume — a premise Jarecki demonstrates with particular cogency through another kind of trickery, in his handling of the interviews with Arnold’s younger brother. I won’t reveal what kind of trickery, but it’s one more demonstration of this movie’s basic modus operandi: strategic concealment followed by offhand candor, which is an excellent way of teaching us how our responses are constructed.