This appeared in the June 18, 2004 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

Bitter Victory

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Nicholas Ray

Written by Rene Hardy, Ray, and Gavin Lambert

With Richard Burton, Curt Jurgens, Ruth Roman, Raymond Pellegrin, Anthony Bushell, Andrew Crawford, Nigel Green, and Christopher Lee.

Jane Brand: What can I say to him?

Captain James Leith: Tell him all the things that women have always said to the men before they go to the wars. Tell him he’s a hero. Tell him he’s a good man. Tell him you’ll be waiting for him when he comes back. Tell him he’ll be making history. —Bitter Victory

This week, as part of its series devoted to war films, the Gene Siskel Film Center is showing a restored version of Nicholas Ray’s little-known masterpiece Bitter Victory—a powerful, albeit flawed, black-and-white CinemaScope feature set mainly in Libya during World War II. This 1957 film offers a radical reflection on war, and its relevance to the current war in Iraq goes beyond the desert settings and references to antiquity.

Many films are regarded as antiwar, including ones that proceed from antithetical premises; in the 60s a popular revival house in Manhattan liked to run a double bill of Grand Illusion and Paths of Glory. Ray’s critique—parts of which could probably be traced back to his radical activism during the Depression, before he turned to making movies—is deceptively simple. On the surface the story concerns a courageous hero, Captain James Leith (Richard Burton), quoted above, and a cowardly villain, Major David Brand, Leith’s superior (Curt Jurgens)—the husband Jane (Ruth Roman) refers to. Both men are assigned to a special unit that’s being sent from Cairo to steal important documents from Rommel’s Nazi headquarters in Benghazi. Leith, a Welsh archaeologist who has previously lived in Libya, has little military experience, and Brand has spent most of the war behind a desk. Both men want the assignment despite the enormous dangers. Leith and Jane were lovers before the war, until he departed without warning for Libya, and—shades of Casablanca—she then married Brand even though she was still in love with Leith. Brand realizes she’s attracted to Leith when he sees them dancing together in a restaurant, and he becomes sick with jealousy. Shortly afterward, he and Leith leave for Benghazi.

Disguised as Arabs, they stand outside the Nazi headquarters, and when Brand can’t bring himself to stab a sentry with a dagger, Leith does the job for him. They successfully seize the documents, but their return trek across the desert becomes a series of ordeals and disasters, made even more agonizing by their mutual enmity.

Bitter Victory may well be Ray’s most ambiguous and disquieting work—its only competitor in his oeuvre is the similarly pessimistic Bigger Than Life (1956), which makes ordinary American middle-class life look almost as deranged as war does here. Bitter Victory, made when he was in his mid-40s, was his first attempt to break away from Hollywood, and judging by Bernard Eisenschitz’s biography of Ray and a recent memoir of screenwriter Gavin Lambert, the production was extremely troubled.

Ray was in California when he began adapting a French novel by Rene Hardy with Hardy and Lambert, the former editor of the English film magazine Sight and Sound. Ray had brought Lambert to Hollywood as a screenwriter (on Bigger Than Life and The True Story of Jesse James) and as a lover. Their relationship was on the wane when he accompanied Ray to North Africa to scout locations and then to Paris, where Ray hired blacklisted writer Vladimir Pozner to make script revisions without the knowledge of producer Paul Graetz. Graetz would later insist on rewrites by Paul Gallico that Ray would either alter or ignore. To complicate matters further, Hardy had final script approval.

The casting was also tragicomic. Ray wanted Burton, but as Brand rather than Leith (for whom he wanted Montgomery Clift or Paul Newman). His choice for Jane was Moira Shearer, and he wanted Jurgens, who was German, to play a captured Nazi officer, not Brand. (To explain Brand’s accent, Graetz insisted on adding an early line of dialogue identifying him as a Boer, and he apparently hired Gallico in response to Jurgens’s complaints that his character wasn’t sufficiently sympathetic.)

Things got more chaotic. Lambert was fired by Graetz after refusing to report back on Ray’s drinking (a real problem), though Ray continued to phone him regularly. Behind schedule, Ray shifted to studio shooting in Nice and Paris. He spent his evenings gambling compulsively—losing $60,000 one night in Monte Carlo—and got involved with an 18-year-old Moroccan girl who was a heroin addict. By the time he completed the film’s sound mixing he had to be hospitalized for exhaustion.

What relevance does all this have to the finished film? A great deal. On the numerous occasions when I met Ray in Paris and New York during the 70s, he, like Ernest Hemingway, seemed a victim of his own macho poses, something his biography only confirms. I once found him stranded in the rain in Paris around 10 AM and invited him to a nearby cafe for a drink; he promptly ordered, with an obvious touch of bravado, tequila and a beer chaser.

In Bitter Victory Ray repeatedly exposes the childish vanity of such behavior, making the film a ruthless autocritique that’s periodically confused or at least complicated by the casting. (An earlier foray in the same general direction was his semiautobiographical noir masterpiece of 1950, In a Lonely Place.) Ray’s bisexuality may have given him insights into gender codes, including macho attitudes. He exposes not only the painfully obvious self-absorption and self-deception of Brand, but the same, less obvious traits in Leith, who’s played by Burton in his most suave, romantic, literary Welsh manner, gets the best lines and most quotable rejoinders, and is seen by everyone else in the film as heroic, especially alongside Brand, who’s regarded as a hypocrite. Yet the film’s dialogue and story, including the opening and closing scenes with hanging stuffed dummies used for bayonet practice, are full of ambiguities regarding motives and behavior, and they ultimately imply that he’s a smug poseur. He’s determined to have the last word on every subject, dishonest about his feelings for Jane, and infatuated with his own nihilism and suicidal despair (which we’re also expected to relish). Meanwhile, the hapless Brand is much less successful at hiding his feelings–Jurgens, with his plaintive cocker spaniel eyes, plays him as a classic cuckold figure–and is treated by everyone as a scapegoat.

If Ray had had his way with the casting, the antagonists surely would have been more evenly matched. Nevertheless, the better acquainted I’ve become with this film over the years, the more questionable Leith’s overdetermined charisma becomes. When Brand shows real courage by being the first to drink from a well that may have been poisoned, Leith immediately dismisses the act as another attempt to cover his shame for his previous cowardice, implying that there’s no way he could ever redeem himself. Yet earlier Leith has been ordered by Brand to stay with two dying soldiers, and he finds the “courage” to shoot the German but not the “courage” to put one of his own men out of his misery, even after the man begs to be shot. We come to realize that both men are ultimately condemned by the rhetoric of war to assume absurdist positions: as Leith eloquently puts it, “I kill the living and I save the dead.” And as English critic Geoff Andrew has pointed out, Leith is more generally a coward “since he fears life itself.”

In either case, you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t. Any form of self-testing becomes a futile macho pose—an infantile form of acting out encouraged by war and the license it provides. The film’s mix of psychoanalysis and existentialism also implies that bravery and cowardice might even be alternate versions of the same cheap impulse—the positive and negative sides of the same dubious mythology. In the end the issue isn’t whether wars accomplish good things or bad things—we never get a clue about why the captured documents are important—but why some men seek them out or welcome them.

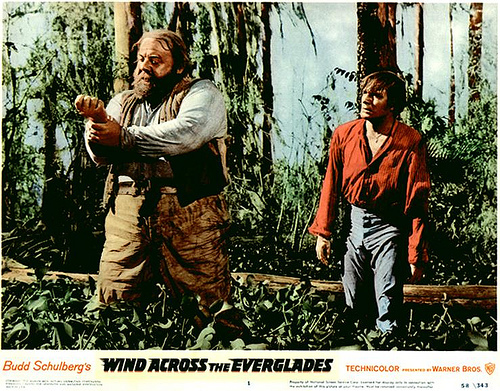

This isn’t the only Ray film to offer male antagonists who achieve a kind of mystical equality. In Wind Across the Everglades, the next film he directed, in 1958, an Audubon Society game warden (Christopher Plummer) and a renegade bird trapper (Burl Ives) in the swamps of Florida wind up as temporary drinking buddies and fellow celebrators of “protest.” In Rebel Without a Cause (1955) Jim Stark (James Dean) and Buzz Gunderson (Corey Allen) are teenagers arriving at an unexpected rapport and moment of mutual recognition immediately before competing in the absurdist macho ritual of a “chickie run.” Bitter Victory takes this premise further, depicting rivals who can find neither friendship nor understanding but whose identities are eerily fused, like Jekyll and Hyde.

The film’s final scene with the stuffed dummies makes this idea inescapable—a scene missing from the truncated original release in the UK, which must have made nonsense of the rest. (That version was 90 minutes long, the original U.S. release was 82, the French dubbed version 87; the restored version showing at the Film Center runs 103.) Prisoners of the rhetoric of war, both men are literal as well as figurative dummies; Leith simply has the better cover story, making him even worse in some ways than his honestly bumbling and universally scorned rival. On a more mystical level, the two men become morally and existentially equivalent: Leith, who loves Jane, has consistently lied or been evasive about his feelings for her, but Brand, lying to her about what he thinks Leith’s final words for her might have been, imagines they were a declaration of love and tells her they would have been his last words as well—and in his case we know that’s the truth.

“Basically [Ray] was both of them,” Lambert is quoted as saying in Eisenschitz’s book. “And I think that was the mainspring of the film for him….I liked the idea that the outcome of the mission [really had] nothing to do with how they performed it, but with what they felt about each other. That, in a way, said something about war. That it was an example of people’s neuroses coming out. And that if people could discover how neurotic they were in a war…it might never have happened.”

A dozen years ago in Rotterdam, I attended a special screening of Bitter Victory, part of a symposium about the first gulf war, which was then in progress and being widely celebrated in the U.S. The second gulf war hasn’t been celebrated nearly as much—at least not since the infamous “mission accomplished” banner flew behind Bush as he spoke on an aircraft carrier—and the increasing relevance of the film to this country’s queasiness about it starts with the title.

Shortly after 9/11 Bush declared war on terrorism and was almost immediately transformed from an unpopular president who seemed unsure of himself into a popular one who exuded confidence and purpose—in the process switching from a Brand to a Leith. And his use of the word war magically helped transform the terrifying and unfathomable singularity of the terrorist attacks into something far easier to process. September 11 was miraculously made to rhyme with Pearl Harbor, and we were suddenly back on familiar ground. Even if war on terror conjured up a military engagement with no conceivable end, that was OK because it somehow felt right—it brought back the patriotism of previous military campaigns, including the cold war, and evoked the nostalgia of wartime unity embodied in a movie like Casablanca. The use of the word war told us that we were all together again, all members of the same family—the same thing that reverent saturation TV coverage of Reagan’s funeral proceedings told us, at least if we could bear watching it.

But then, after we were told it was virtually over, the Iraq war resumed. The possibility that we might be witnessing a war of independence fought by citizens who didn’t like being occupied didn’t fit the idea of war as Bush and his minions in the media were using it.

Their war has more to do with abstraction and fixed notions of good and evil than with human beings– which might be why Bush favored a war on terror over a war on terrorists. The chosen catchphrase sounds more metaphysical and more frightening, limiting the need to provide detailed arguments and explanations and making it easier to rationalize things such as torture—even after the Red Cross reported that military officials estimated 70 to 90 percent of the people imprisoned in Abu Ghraib were there by mistake. (Some people, including Fox News pundits, went even further and defended the torture.) The abstract slogan also seems to have made it easier for Bush to call both Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein evil—without acknowledging that both men are former U.S. allies and without coming up with some explanation for why they weren’t evil when the U.S. supported them, or why they were less evil at that time than communists or Iranians, or why the U.S. was wrong then but is right today.

But that would require an admission that the world is never as simple as Bush and so many others want to believe, even when it comes to evil. It might also require them to recognize that war isn’t just a real activity with real consequences but a playing out of infantile and macho fantasies. And so we all become like Leith, who’s trapped in his own rhetoric, or like Brand, who feels so hollow about the medal he’s been handed that he pins it on a dummy.