From the Chicago Reader (August 20, 2004); I revised this slightly in June 2011. — J.R.

Revolution ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Stephen Jones

Written by Bob Avakian

With Avakian.

Queimada **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Gillo Pontecorvo

Written by Franco Solinas and Giorgio Arlorio

With Marlon Brando, Evaristo Marquez, Norman Hill, and Renato Salvatori.

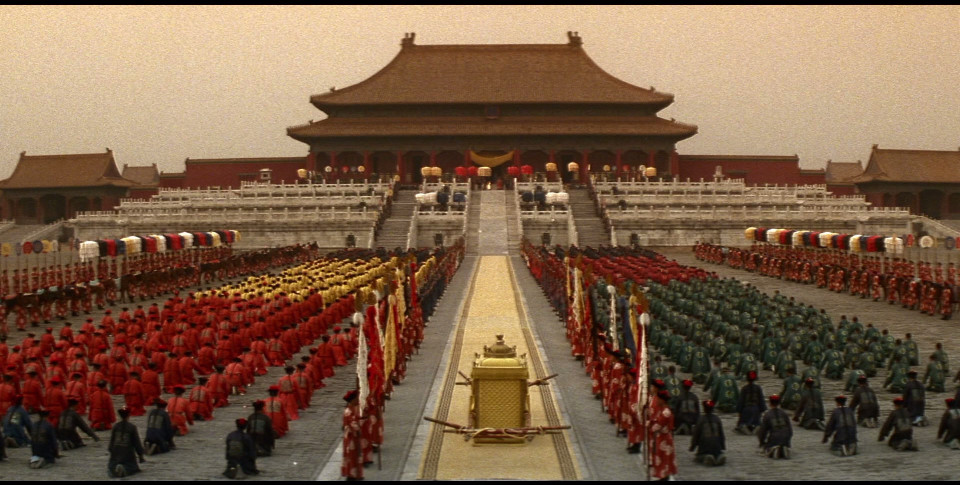

The Last Emperor **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by Mark Peploe and Bertolucci

With John Lone, Joan Chen, Peter O’Toole, Ruocheng Ying, and Victor Wong.

August is traditionally the month when films people don’t know what to do with surface, a time when those films are less apt to be noticed. This August three of these films happen to be about revolution. Actually Revolution, showing Wednesday at the 3 Penny, isn’t a movie but a DVD of the first 136 minutes of a long, four-part lecture by Bob Avakian, chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party USA, in what is reportedly his first public appearance since 1979. The other two are director’s cuts of celebrated movies, both being screened here for the first time. Marlon Brando wrote in his autobiography that Gillo Pontecorvo’s Queimada (1969), showing several times this week at the Gene Siskel Film Center, contains “the best acting I’ve ever done,” and Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor (1987), screening August 28 at Facets Cinematheque, won five Oscars, including those for best picture and best director. (In his autobiography Brando cites Bertolucci, Pontecorvo, and Elia Kazan as the best directors he worked with, pointedly excluding Charlie Chaplin because of his unpleasant experience during the shooting of the 1967 A Countess From Hong Kong.)

Queimada is better known in this country as Burn!, and it was originally released in a 112-minute version. The director’s cut is 20 minutes longer, but it’s in Italian with subtitles and so Brando is dubbed. (Is it too much to hope for a director’s cut of the English version?) The director’s cut of The Last Emperor is 219 minutes — an hour longer than the version that won the Oscars — and because of its length it’s being shown only once in Facets’ ongoing Bertolucci retrospective. (Also showing only once is the director’s cut of 1900, which clocks in at 318 minutes.) It has been available for quite some time on DVD, though it’s received practically no critical acknowledgment. It’s a tribute to the skill and charisma of Avakian as a lecturer that I wound up watching nearly all 11 hours and 15 minutes of Revolution: Why It’s Necessary, Why It’s Possible, What It’s All About. I found his critical analysis of contemporary America interesting even when he turned to unconvincing Maoist imperatives and strategies, and I found it remarkable that he still believes in the possibility of revolution in this country today. (The lecture’s available in a set of four DVDs or four videos for $34.95 that will be sold at the 3 Penny screening.)

I’ve never been a communist, but by far the best teacher I’ve ever had was one — Heinrich Blücher (1899- 1970), the husband of Hannah Arendt. He taught comparative ideas and philosophy at Bard College, and even in the supposedly enlightened America of the mid-60s it would have been dangerous for him to let on that he was once a member of the German Communist Party, so I didn’t know about this part of his background at the time. I knew him as a humane, witty, earthy, no-bullshit European intellectual who was self-taught and unpretentious. Discovering after his death that he’d been a Spartacist and Communist Party member was a bit like receiving a posthumous chapter in his ongoing history lessons. The implication was, among other things, that communism could be a useful tool of analysis and reflection and not simply the strategy of the enemy.

Avakian isn’t remotely in Blücher’s league, but his communist analysis is graceful, and he lucidly explains concepts ranging from dialectical materialism to irony without condescending to his audience. (Like a Richard Pryor concert film, Revolution cuts between different versions of the same material — in this case, the same all-day lecture given on the east and west coasts in 2003.) He’s no less sharp when he’s answering questions than when he’s outlining his revolutionary program. Regrettably, the portion of his lecture that’s being screened is devoted largely to American atrocities such as lynchings, stories he often punctuates with “And that isn’t the worst of it.” These stories are true and relevant in some ways, but it’s distressing that he’s completely silent when it comes to the horror stories of Stalinist Russia and Maoist China — including the tens of millions of people killed under each regime. Yet this gaping absence, however reprehensible, doesn’t necessarily invalidate the remainder of his lecture. After all, we wouldn’t argue that the Crusades and the Spanish Inquisition make it impossible to take any part of Christian doctrine seriously.

When asked what his favorite movie is, Avakian briefly describes Burn! before listing other titles. This film fared poorly at the box office in 1969, but it’s been the favorite of many revolutionaries ever since. Like Pontecorvo’s preceding and better feature, The Battle of Algiers (1965), it mainly recounts a revolutionary defeat — eliding most of the violence and bloodshed and concentrating on the aftermath of various skirmishes — though it ends with a noble evocation of revolutionary aspirations. Also like its predecessor, Queimada tells a story that’s basically impersonal: not only is there no “love interest,” but women tend to play an incidental, mainly decorative role.

Brando plays a foppish agent provocateur named Sir William Walker who’s working for the English government in the 1830s. He helps instigate a revolution by black slaves on a fictional Caribbean island named Queimada — Portuguese for “burned,” which was what the Portuguese settlers did to the crops of the original inhabitants — because the English believe a revolution will break the Portuguese sugar monopoly. (In the original script it was a Spanish sugar monopoly and the title was the Spanish Quemada, but the Spanish government demanded a revision.) Ten years later a sugar company hires Walker to return to Queimada and help crush the same revolution. During each period we see him operating mainly as a remote if highly intelligent functionary. His motives are ambiguous even the few times he’s seen acting independently — in a barroom brawl just before he returns to Queimada in the 1840s and when he tries to save the life of the defeated rebel leader (Evaristo Marquez). Cruel intelligence is largely what sets Walker apart from other Brando heroes and antiheroes, who are generally dumb and sensitive. He’s used to illustrate various Marxist notions about labor, power, capital, and empire — Pontecorvo joined the Italian communist party in 1941, though he quit in ’56, presumably in response to the Soviet invasion of Hungary — but thanks to Brando’s talent, this doesn’t dehumanize him. Pauline Kael praised Burn! as an inspired failure, improbably comparing its ambition to fuse art and politics with that of Sergei Eisenstein. Predictably, she saw it as a parable about American involvement in Vietnam, writing of Brando’s Walker, “He appears to be a super-cool C.I.A.-type mastermind crossed with Lawrence of Arabia.” Today more relevant parallels might be found in this country’s privatization of government services and in its sponsorship and subsequent demonization of Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein.

Writing about The Last Emperor in these pages in 1987, I noted that Bertolucci’s career-long efforts to reconcile Marx and Freud — evident even before 1969, the year he joined the Italian communist party and started Freudian analysis — finally seemed to bear fruit in this biopic about Pu Yi (1906-’67), mainland China’s last official emperor (John Lone)

The extra hour in the director’s cut allows Bertolucci to elaborate on this synthesis, though I’m not sure it makes his topic any more lucid or engrossing. In both versions the journey from imperialism to communism is viewed as a kind of moral progress as well as a psychic evolution. The reconciliation of Marx and Freud is predicated on the continuities as well as divergences seen in Pu Yi’s two key father figures: Reginald Fleming Johnston, his Scottish tutor and imperialist adviser (Peter O’Toole, Lawrence of Arabia himself), and Jin Yuan (Ruocheng Ying), the kindly yet stern governor of the detention center where Pu Yi spent ten years getting a Maoist reeducation. (The real-life Jin Yuan has a cameo as the prison official who eventually hands Pu Yi his pardon.) “In my view,” Bertolucci said around the time the film was first released, “the brainwashing story corresponds to a kind of forced psychoanalytical itinerary.” The process by which psychological and symbolic categories are converted into social ones is epitomized by a climactic exchange between the former emperor and the governor: “You’ve saved my life to make me a puppet in your play,” says Pu Yi. “The Imperial City has become a theater without an audience. So why did the actors steal all the scenery?” Jin Yuan replies, “Is that so terrible — to be useful?”

Years later Pu Yi sees Jin Yuan being punished as a traitor by the Red Guard. This is Bertolucci’s only major acknowledgment of the brutal injustices of the Cultural Revolution, but given that this film is telling the story of the conversion of an individual from imperial figurehead to ordinary citizen, it may be sufficient. For like any proper Freudian biography, The Last Emperor basically charts the adoption and loss of various parental substitutes. When Jin Yuan sees that Pu Yi’s former servant is still dressing him in prison he moves the ex-emperor to another cell. Pu Yi protests that he’s never been separated from his family before — a seemingly irrational statement until one realizes that the servant is the most recent in a long line of family surrogates that has included Pu Yi’s wet nurse, his two wives, and his concubines.

This film pales alongside Eisenstein’s unfinished Ivan the Terrible trilogy, another Freud-Marx synthesis, but it’s one of the few films that’s comparable in its audacious effort to combine a submerged psychosexual autobiography with a historical epic that has contemporary political meaning and in its attempt to negotiate an almost impossible merging of obsessive personal allegory and state-sanctioned propaganda, both Chinese (the government’s view of itself) and American (the “opening” of China as inaugurated by Richard Nixon). The key differences are that Bertolucci was delving into a culture radically different from his own, shooting in English, a language that belonged to neither culture, and taking no serious personal risks. Eisenstein, working within his own culture under the watchful eye of Stalin, was risking his life at every turn.

The flashbacks that organize The Last Emperor — it begins by alternating between 1950 Manchuria and 1908 Peking — reflect the film’s ideological conflicts as it cuts repeatedly between past and present like a restless insomniac. This was Bertolucci’s second quixotic and contradictory attempt, after 1900, to sell communism to a Western public, and it’s much more ideologically canny than its predecessor. The cheese in this particular mousetrap is the opportunity to identify with the emperor and his privileges, including the kinky sex. (In Reds, by contrast, Warren Beatty offered a relatively prudish if bohemian romantic fantasy.) It’s a tribute to the film’s intelligence and its feeling for dialectics that it views both the Forbidden City and the detention center as prisons, and that when Pu Yi winds up as a gardener there’s a sense of gain as well as loss.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|