From the Chicago Reader (January 28, 2005). — J.R.

Notre musique

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

With Sarah Adler, Nade Dieu, Godard, Rony Kramer, Mahmoud Darwich, Jean-Christopher Bouvet, Simon Eine, Juan Goytisolo, Peirre Bergounioux, George Aguilar, Leticia Gutierrez, Jean-Paul Curnier, and Gilles Pequeux.

Jean-Luc Godard has had a tendency to be combative and obscure. He’s a lot calmer and steadier in his latest feature, Notre musique, opening this week at the Music Box. He’s also been making an effort to express his intentions clearly and simply in interviews, including those with the mainstream American press. Yet some viewers will probably still feel excluded and puzzled by his methods as a filmmaker and his habits as a thinker, however beautiful and powerful the results.

Even if one can deal with Godard’s compulsive use of metaphor and abstraction and his Eurocentric perspective — all standard in much of his late work — there’s something morose and emotionally remote about this film. Around a sense of futility, a disenchantment with the world, he builds a kind of poetics that’s akin to some of the excesses associated with German romanticism. The issue isn’t whether such despair is warranted, but what one does with it. Now in his mid-70s, Godard appears to have settled on a meditative view of contemporary history and seems disinclined to explore fresh tactics for addressing problems.

A similar tone of lament is apparent in some of the last published pieces of Susan Sontag, one of Godard’s earliest and staunchest American champions. Born only a couple years after Godard, she remained a tireless social and political activist, unlike him. (She was widely criticized for some of the forms her activism took, such as staging a production of Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo when the fighting was still going on — a gesture of solidarity that can best be judged by the people it was directed toward.) Yet what she called the “seriousness” of many of her late statements is as emotionally intractable as Godard’s pessimism. I usually sympathize with their compassion for the underdog in most wars, though each offers many ways to brood about the world and few strategies for doing much else.

Divided into three sections (or “kingdoms,” as Godard calls them) like Dante’s Divine Comedy, Notre musique begins with ten minutes of a very persuasive hell and ends with ten minutes of a very unpersuasive heaven. The hour of purgatory in between encompasses the slender plot: people attend a conference in Sarajevo called “European Literary Encounters” and walk around the city. Godard himself gives a lecture to students on “text and image,” much of which turns out to concentrate on “shot and countershot.”

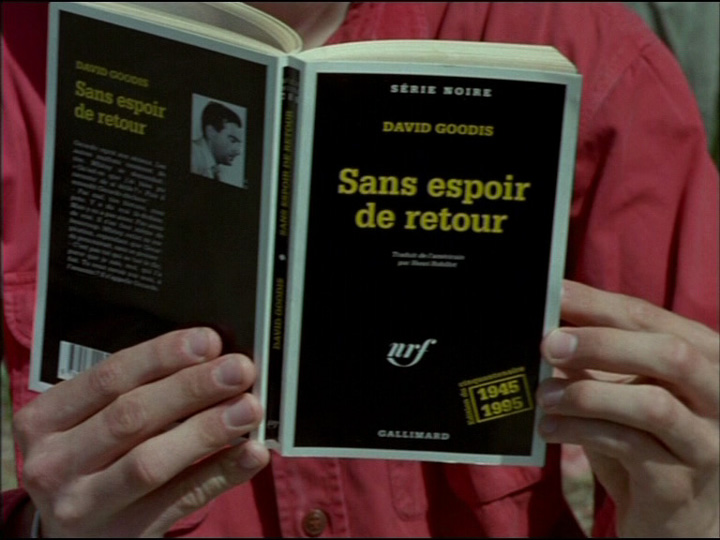

Insofar as text and image can be distinguished from each other, Godard’s hell consists mostly of text (specifically documents or film clips) and his heaven consists mostly of image (specifically his own attractively framed images). The first ten-minute stretch of Notre musique is essentially a silent film, complete with piano accompaniment, and the images are all found footage of warfare. It’s here above all that Godard displays his remarkable gifts as an editor. Though 20th-century conflicts dominate, the wars shown represent all wars, and, in a radical tactic, he makes no distinction between fictional and documentary footage — just as in his purgatory and heaven he freely mixes actors with people playing themselves. His heaven consists of an idyllic green forest beside a lake in no specified country where people play games, wander, munch on an apple, or read (here we see this segment’s only visible text, a French translation of David Goodis’s Street of No Return). We also see marines carrying rifles and standing guard alongside chain-link fences. Unattributed citations form the bulk of what we hear during the film, as they do in most of his work; the Tribune‘s Michael Wilmington pointed out to me that the last sentence uttered in the film is a paraphrase of the final line in Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely.

As James Quandt notes in his thoughtful reflections on the film in the Winter 2005 issue of Cinema Scope, Godard’s ten minutes of hell can be traced directly to his 2000 video Origins of the 21st Century — one of many pendants to his magnum opus Histoire(s) du cinema (1998), which views film, both fiction and nonfiction, in relation to the history of the 20th century and ultimately finds it wanting because it didn’t adequately bear witness to the Holocaust. As a result, even the materials he’s amassed to represent hell — including such fictional sources as Alexander Nevsky, Kiss Me Deadly, Zulu, and Apocalypse Now and diverse kinds of newsreel and documentary footage — are implicitly tainted. Nevertheless, the way he juxtaposes them creates new meanings and gives them a different impact.

Godard offers us another duality in the form of two young Jewish Israeli journalists at the conference, Judith Lerner (Sarah Adler) and Olga Brodsky (Nade Dieu) — “one drawn to the light and one drawn to the darkness,” as the film’s press book puts it. The narrative placement of these characters recalls portions of Godard’s 60s work — his most exciting period, before he sank into the dogmatic pronouncements of his post-’68 Marxist phase, when he was functioning as a kind of journalist, intentionally or not.

Unfortunately, the fates of these characters recall the more confused aspects of the work of that period. After the conference a French-Israeli participant Godard met when he arrived at the airport calls him in his garden in Switzerland to report that Olga, who sympathized with the Palestinian cause, was killed after taking hostages in a Jerusalem cinema and threatening to blow herself up. She let the hostages go, then was shot by marksmen, and when they opened her shoulder bag they found only books inside. This recalls the absurdist, accidental murder described at the end of La chinoise (1967), committed by a Maoist (Anne Wiazemsky) — though it also echoes Godard’s reply to a question asked by Judith shortly after he arrives in Sarajevo. “Why aren’t revolutions started by the most humane people?” she says. He replies, “Because humane people don’t start revolutions. They start libraries.” “And cemeteries,” says someone else. In the last section — which recalls the wandering hippie guerrillas/cannibals at the end of Week End (1967) — the main character is Judith, though when she speaks her voice is Olga’s.

As fanciful as they were, La chinoise and Week End were valuable as journalism because they expressed political ideas that were circulating at the time in Europe and the U.S. The accidental murder in La chinoise, like Olga’s futile self-sacrifice in Notre musique, can be interpreted as Godard’s acknowledgment of his impotence as an intellectual, and the bucolic setting and cannibalism in Weekend gave his overall endorsement of the radical student left a disquieting edge. I assume the marines are in Notre musique to give his latest version of paradise a disquieting edge — though even if they weren’t there I’d find this heaven unconvincing.

Godard is relatively reclusive today, so one can’t glean much that’s journalistic from Notre musique apart from the material relating to Sarajevo and the examination of various texts. Yet he still has things to teach us about the way our responses to image and text tend to be coded and predetermined — something that’s especially evident during his illustrated lecture. Holding up a photograph of charred ruins, he asks the students where it was taken, and they suggest sites in eastern Europe and Japan. “No,” he says. “Richmond, Virginia, 1865.” Our music has clearly been playing for centuries.

When a student asks Godard, “Can the new digital cameras save cinema?” he remains silent. Many reviewers have taken this to be some kind of sarcastic put-down, but Godard recently explained that it was just that he had, and has, no answer. The most beautiful and telling moments in Notre musique derive from a similar modesty — from the simple act of bearing witness.