From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 2005). — J.R.

I Am Cuba, Siberian Mammoth

*** (A must see)

Directed by Vicente Ferraz

The Journey: Portrait of Vera Chytilova

no stars (Worthless)

Directed by Jasmina Blazevic

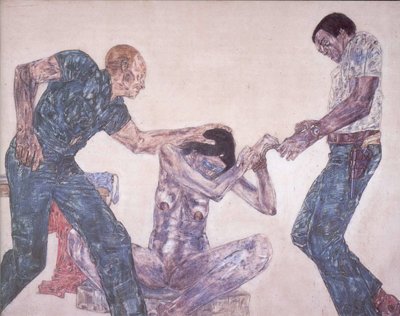

Golub: Late Works Are the Catastrophes

*** (A must see)

Directed by Jerry Blumenthal and Gordon Quinn

I Am Cuba, Siberian Mammoth is a 2004 Brazilian documentary about the making of the legendary 1964 Russian-Cuban production I Am Cuba, a preposterous, beautiful, mannerist epic of Marxist agitprop celebrating the Cuban revolution. Early on the documentary — which, like the other two films reviewed here, is showing this week at the Chicago International Documentary Festival — focuses on one of the key sequences in the original film. The coffin of a radical student slain by Batista’s police during a mass uprising is carried by his comrades through downtown Havana, surrounded by a crowd that swells to Cecil B. De Mille proportions. In a delirious, breathtaking two-and-a-half-minute shot, the camera moves ahead of a young woman and past a young man — catching him in close-up as he turns around, hoists the front of the coffin onto his right shoulder, and walks away with the other pallbearers — then cranes up the five floors of a building, past people watching from balconies and parapets. The camera moves to the right across the street and through a window into a cigar-rolling factory, where it follows workers as they hand a Cuban flag one to another, eventually unfurling it from a window. The camera moves out that window and over the flag, then follows the funeral cortege from above for what seems like a quarter of a mile.

After showing this black-and-white shot, Vicente Ferraz’s documentary offers a color shot of a Cuban man on what may be the same street today as he recalls what a great shot it was. But he doesn’t remember that he was the young man who turned around in close-up while lifting the coffin until Ferraz tells him.

The man was the most prominent individual in one of the most spectacular shots in film history, and his inability to remember that 40 years later speaks volumes about what it means to be inside a revolutionary movement. That the funeral was either fictional or restaged for the camera is secondary, because we learn that for this man in the 60s, being part of the Cuban revolution and being part of I Am Cuba were separate aspects of the same experience. He makes clear that it was the collective moment that mattered then, not his individual participation in it.

There’s no question that I Am Cuba is a misguided piece of communist kitsch that failed to achieve its stated objectives. In an apt quotation that concludes Ferraz’s film, the Village Voice‘s J. Hoberman calls it a “Bolshevik hallucination.” It was received disastrously in both Cuba and the USSR and shelved shortly after its premiere, only to be rediscovered by the West in the early 90s and turned into a cult item. Yet it remains an implied rebuke to the auteur-based model of art cinema that’s ruled the West since the 60s. Everyone Ferraz interviewed describes it as a collaborative venture — one can’t credit its virtuosity, style, or content simply to director Mikhail Kalatozov or cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky or writers Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Enrique Pineda Barnet, as Western critics are wont to do. (Ferraz’s documentary also makes clear that there was another significant creative voice in the mix, Urusevsky’s wife, Bella Friedman, the first assistant director and apparently the key figure linking the Russian and Cuban workers on the film.) Even the Western tendency to associate a style of camera movement with one individual’s sensibility is challenged, because the camera was sometimes relayed between crew members over the course of a single shot.

It seems a bit facile and ironic that Ferraz summarizes I Am Cuba‘s current reputation by using ad copy. Hyperbolic adjectives are plastered over the documentary’s VHS and DVD cases, one adjective per publication: “beautiful” from New York magazine, “exquisite” from the LA Weekly, “ecstatic” from the Washington Post, “dazzling” from Interview, and so on. One person Ferraz interviews in the film remarks that I Am Cuba was shunned when it was needed and celebrated only after it became a museum piece. He has a point, though it wouldn’t be hard to make the same point about Citizen Kane. But given that Citizen Kane has been the standard bearer for auteurism since the 60s, it’s far more interesting and significant that I Am Cuba‘s Wellesian style and sense of bravura aren’t the result of any one individual’s effort.

I’ve been a fan of Vera Chytilova, a radical and transgressive Czech filmmaker, ever since I saw About Something Else (1963), Daisies (1966), Fruit of Paradise (1970), and The Apple Game (1976) in the 70s (only Daisies is available in the U.S.). The later works I’ve managed to see proved uneven, so I hoped Jasmina Blazevic’s The Journey: Portrait of Vera Chytilova (2004) would offer some insight. But it was frustrating and disappointing. Blazevic shows Chytilova without a context beyond her house, her family, and her abstract sense of herself — and Chytilova has little of interest to say about any of them. None of the few clips shown is identified before the end credits, and though Chytilova complains in passing that she wasn’t able to make films during a few stretches in her career, we don’t learn why — we don’t even learn when these stretches were. The feminist provocation, formalist high jinks, and political incorrectness of Daisies scandalized Czech Communist officials, but there’s nothing about any of this either in Blazevic’s film.

About Something Else cuts repeatedly between two seemingly disconnected stories about different women, establishing formal rather than thematic links between them, and Daisies features two mischievous teenage girls with the same name. Both films suggest that personal identity can get lost within a larger order, though a director with a sharply defined personal identity is clearly establishing that order. Blazevic doesn’t offer any clarity on the identity at work here, giving us instead the lowdown on what Chytilova thinks of herself as a kvetching grandmother today.

In the 60s and 70s Western cinephiles were focused on exemplary leftist figures like Jean-Luc Godard and Bernardo Bertolucci, even though much more politically and formally radical work was being done by Eastern European directors such as Chytilova, Dusan Makavejev, and Miklos Jancso — all of whom were struggling against yet also working within Communist regimes. Blazevic does nothing to help us understand this conundrum.

Golub: Late Works Are the Catastrophes (2004) is an updated version of the masterful 1988 documentary about leftist painter Leon Golub, by the Chicago-based Kartemquin collective. (I gave it a four-star review in the Reader 16 years ago.) The film has now been expanded from 52 to 78 minutes, and watching it, I found myself alternately grateful, dismayed, and bemused, because it’s no longer the same film in form or content.

The original Golub, which was directed by Jerry Blumenthal and Gordon Quinn, essentially shows the production of a single painting in 1985, from its conception through its execution, followed by its reception at a gallery in Ireland. Golub himself offers commentary during all stages of the process, and gallery attendees record their reactions.

The new version is exactly the same, but with an extended epilogue that Blumenthal directed alone (Quinn remains as coproducer). The epilogue describes Golub’s subsequent evolution as a painter, concluding with an overview of his relationship with his wife, Nancy Spero, and a brief consideration of her painting. Golub again provides a running commentary. Here too, a few gallery viewers are seen looking at paintings, but they’re almost never heard; the only prominent voices are Golub’s, Spero’s, and the filmmakers’. What begins as a film about this painter’s work, its political sources and political impact (like I Am Cuba, Siberian Mammoth), now evolves into a softer, vaguer, more personal film about a life (like The Journey), in which the work plays a lesser role — a shift that’s reflected in his own changing relation to politics. The early work we see is about violent oppression, specifically contemporary events in Nicaragua and Africa. The late work is more playful, focusing more on eroticism than violence, and more fatalistic, turning away from the sociopolitical world and focusing more on animals — dogs, a tired, aged lioness — than on people.

The documentary’s new subtitle comes from one of the later paintings, and it’s hard not to read it as also referring to Kartemquin’s late works — or at least to this particular one. The new section shows a sequence that was cut from the original film, one that somewhat romantically implied that Golub’s paintings could goad viewers into political action. Golub told Blumenthal and Quinn that was going too far, and they rightly dropped it. Now they seem to have gone to the opposite extreme, giving up on the idea that art can have any political effect.

Golub, who died last year around the time the film was being completed, is as intelligent and provocative in the epilogue as he was in the 80s. But the epilogue undercuts the intelligence, the provocativeness, and the shapeliness of the original Golub.