From the Chicago Reader (May 19, 2006). — J.R.

The Lost City

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Andy Garcia

Written by G. Cabrera Infante

With Garcia, Steven Bauer, Richard Bradford, Nestor Carbonell, Lorena Feijoo, Bill Murray, Dustin Hoffman, Tomas Milan, and William Marquez

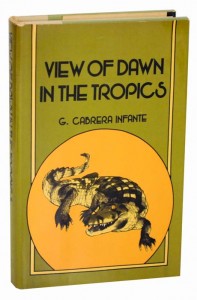

An intellectual initially associated with Castro’s revolution, G. Cabrera Infante (1929-2005) founded the Cuban Cinematheque and was known as both the Cuban James Joyce and the Cuban Laurence Sterne. He spent his final 39 years in voluntary exile in London, and his last screenplay was for The Lost City, the first feature directed by Andy Garcia. Among his works available in English are the novels Three Trapped Tigers, View of Dawn in the Tropics (the most succinct and measured, and my favorite), and Infante’s Inferno; his nonfiction includes Holy Smoke (a tribute to Havana cigars, his first book written in English) and A Twentieth Century Job, a collection of film criticism published under the pseudonym G. Cain (derived from his first initial and the first two letters of Cabrera and Infante). And there’s the screenplay for the 1971 Hollywood thriller Vanishing Point, also credited to Cain.

Sixteen years ago Garcia decided he wanted to adapt Cabrera Infante’s unadaptable, pun-packed, joyfully multicultural Three Trapped Tigers, an epic about Havana nightclub life during the late Batista period. Garcia’s dream kept mutating, and Cabrera Infante wound up writing a gargantuan screenplay with an entirely new story line. As Garcia tried to get financing, the script kept getting whittled down, and the result is The Lost City, the only evidence of what the original might have been like. This raises the same kind of questions as A.I. Artificial Intelligence, whose 40-page precis, as commissioned by Stanley Kubrick, was realized by Steven Spielberg only after Kubrick died. Garcia says Cabrera Infante saw the finished film before he died but doesn’t say what he thought of it. It’s especially hard to imagine how he responded to the grotesque representation of himself, a strained comic part played by Bill Murray (Garcia’s real-life golfing buddy). Until I read it in the press book I had no idea that Murray, in his mock-jock persona, was supposed to evoke Cabrera Infante, who was given to dandyish dress and constructed a literary image that photographs show was Victorian and Edwardian, like the Anglophilic enthusiasms of Jorge Luis Borges.

Garcia – -who stars in The Lost City as Fico Fellove, owner of a Havana nightclub called El Tropico (based on the real-life Tropicana) until the revolutionaries take it away — left Cuba at the age of five and has never returned. His movie was shot in the Dominican Republic, and according to some Cuban exiles of my acquaintance, it evokes Miami from a Cuban perspective more than Havana. Garcia’s area of greatest expertise is Cuban pop music, and the movie’s most solid achievements are the score he composed for it and the way he’s built the narrative around songs and their performances.

Otherwise the film suggests a dutiful if clunky pastiche of The Godfather and a right-wing Reds, with Fellove and his brothers and parents representing a spectrum of possible responses to the Cuban revolution. Viewers who think The Godfather and its first sequel are great movies may be more impressed than I am. I’ve always regarded the first film as an efficient but distasteful bit of cynicism about the inevitability and hypocrisy of American crime and the second as a bit of posturing that resembles Stalinist art — the most telling moment may be when Nino Rota’s theme is played on a church organ during a family communion, a clear indication that Paramount has supplanted the Catholic church as the ultimate patriarchal authority in this self-important universe.

Cabrera Infante had a nuanced sense of how the Cuban revolution soured, not a simplistic set of cold war reflexes — his criticism of the idealized radical icon Che Guevara is a lot more complicated than this film’s. His parents founded the communist party in his hometown, Gibara, and he was a leading intellectual in Castro’s Havana before being sent to Brussels as a cultural attache; four years later he settled permanently in London. But the only clear signs of his wit and intellect in The Lost City are in the moral ambiguities that surround the appearances of American gangster Meyer Lansky (a cameo by Dustin Hoffman) and in the film’s final title.

Elaborate printed postscripts often get attached to the end of Hollywood features — a practice popularized by American Graffiti and perhaps used most resourcefully by Albert Brooks. They’re sometimes a response to the interference of studio executives or test marketers, the filmmaker’s final effort to patch things up after they’ve been torn apart — which may explain the closing title of The Lost City.

At the height of his fame and fortune, Fellove is visited by an apparently amiable Lansky, who proposes a partnership running a nightclub and casino, an idea Fellove rejects despite the implicit threat. Eventually he gives up everything, including the woman he loves and what remains of his family, and leaves for the U.S. Once here he finds work as a dishwasher and janitor — and Lansky improbably reappears and makes a similar proposal, this time about setting up a club in Nevada. Fellove doesn’t respond, and the jokey closing title informs us that he opens a nightclub in New York six months later. How he managed to bankroll such a venture isn’t explained, but the clear implication is that Lansky or another gangster footed the bill — suggesting that America is every bit the land of opportunity it’s supposed to be, as long as crooks rather than dictators are supplying the opportunities. This idea reflects Cabrera Infante’s irreverence more than anything else in the movie, and it may be Garcia’s way of giving the writer the last word and of undercutting all the cliches he’s offered up to this point. Too bad it comes across like a whispered afterthought.