From the Chicago Reader (June 23, 2006). — J.R.

Three Times

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien

Written by Chu T’ien-wen and Hou

With Chang Chen, Shu Qi, Di Mei, Liao Su-jen, and Mei Fang

For decades Chinese history has been suppressed in China, on the mainland and in Taiwan, whether the subject is occupation or revolution, communism or capitalism. Recovering that history has become an obsession for art film directors such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, Jia Zhang-ke, Stanley Kwan, Edward Yang, Tian Zhuangzhuang, Tsai Ming-liang, and Wong Kar-wai, whose films are set in both the past and the present.

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Three Times (2005) is split into three episodes set in Taiwan, each running about 40 minutes and featuring Chang Chen and Shu Qi; all three reflect Hou’s overriding concern with the way one’s sense of freedom, desire, and life possibilities is inflected by the age one lives in. The episodes are also about romantic disconnection and failed communication, with the romantic tensions reflecting international ones.

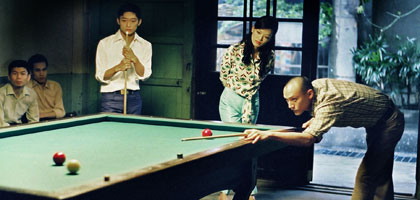

In “A Time for Love,” set in 1966 in Kaohsiung, Chen (Chang) receives his draft notice, then writes a love letter to May (Shu), who works at the snooker parlor where he hangs out. He discovers that she’s taken a job at another snooker parlor, and to the strains of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” and “Rain and Tears” he heads off to find her before reporting for duty. In “A Time for Freedom,” set in Dadaocheng in 1911, during the Japanese occupation, a married diplomat who dreams of Taiwanese independence visits a courtesan (all the dialogue is conveyed in intertitles), and a current of strong feeling passes between them. But he isn’t independent enough to take her as a concubine, and she isn’t independent enough to leave her profession. In “A Time for Youth,” set in Taipei in 2005, with mainland China threatening Taiwan with war, a pop singer avoids her female lover to spend more time with her male lover.

The arrangement of episodes isn’t chronological, which allows a shift from sweet nostalgia to bitter confusion. The film’s Chinese title, which means “The Best of Times,” suggests a further ironic spin on the idea of historical rhymes and regressive developments. Yet despite the titles, it’s the interplay and tension involving love, freedom, and youth that defines all three episodes, especially if these terms are defined broadly, so that love means commitment and devotion as well as infatuation and youth means flexibility and energy as well as innocence.

Seen in isolation, the first episode has the most satisfying plot and the last the least. But the film’s achievement lies mostly in the beautifully articulated similarities and differences among the three—in their compositions and themes, in the way space is defined and camera pans connect characters, in their use of music and other means of personal expression (snooker, pop tunes, and letters in 1966; poetry, singing, and letters in 1911; photographs, singing, and e-mails in 2005), and in the performances of the two stars. Chang, who was discovered by Edward Yang and played the lead in Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991) and Mahjong (1996), has become more identified with Wong Kar-wai, having appeared in Happy Together (1997), 2046 (2004), and “The Hand” (Wong’s episode in Eros, 2004). He’s also in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). Shu has appeared in more than 50 films, including The Transporter (2002).

Some aspects of Three Times evoke Hou’s earlier films, beginning with his trilogy about Taiwan in the 20th century: City of Sadness (1989), The Puppet Master (1993), and Good Men, Good Women (1995, also set during three separate historical periods). The first segment also recalls his 1985 autobiographical film about his adolescence, A Time to Live and a Time to Die, the second recalls his 1998 Flowers of Shanghai (set in a ritzy Shanghai bordello during the 1880s), and the third his 2001 Millennium Mambo (a mainly contemporary film starring Shu Qi). But the structure of Three Times is new for him, which makes all these resemblances superficial.

Discussing the mise en scene of the 1911 segment, Hou has suggested that his creative decisions were simplified by the constraints of a single enclosed set and that the longer 2005 segment was made more difficult because he had most of Taipei at his disposal. The minimalist and formal aspects of the 1911 episode also make that story easier to follow; we’re more apt to feel lost in the 2005 segment, despite the contemporary surroundings, since there’s more information than we can process. Because the 1966 episode has an autobiographical basis, Hou is less distanced from his characters, and this intensifies our response to the romantic feelings.

Late last year Three Times was voted the best undistributed film in critics polls held by the Village Voice and Film Comment. Most of Hou’s 16 other features have screened here at the Film Center, receiving their limited distribution thanks to Wendy Lidell, who acquired them for Wellspring. IFC Films picked up Three Times around the time Harvey and Bob Weinstein picked up Wellspring and promptly pulled from distribution most of its collection, including all its Hou films—resuming their Miramax practice of suppressing more films than they distribute, keeping competitors from showing the films they choose not to. And Harvey Weinstein, who likes to recut the few films he does distribute, has implicitly set himself up as the key artistic figure at Wellspring. All this helps explain why the works of Asia’s greatest living film master will now be harder to see than ever. Three Times, one of the peaks of his career, may be your last chance to see his work inside a movie theater.