My summer 2020 column for Cinema Scope. — J.R.

Well before the coronavirus pandemic kicked in, I’d already started nurturing a hobby of creating my own viewing packages on my laptop. This mainly consists of finding unsubtitled movies I want to see, on YouTube or elsewhere, downloading them, tracking down English subtitles however and whenever I can find them, placing the films and subtitles into new folders, and then watching the results on my VLC player. The advantages of this process are obvious: not only free viewing, but another way of escaping the limitations of our cultural gatekeepers and commissars— e.g., critics and institutions associated with the New York Film Festival, the New York Times, diverse film magazines (including this one), not to mention the distributors and programmers who pretend to know exactly what we want to see by dictating all our choices in advance. (I hasten to add for the benefit of skeptics that my interest in subtitling unsubtitled movies has nothing to do with liking certain films because they’re neglected: I’ve been employing the same practice lately with some of the films of Carol Reed, largely because I like combining the pleasures of reading with those of film watching.)

Case in point: the great Ukrainian/Romanian/Russian/Soviet writer-director Kira Muratova (1934–2018), whose wild and amazing works have never reached the consciousness of most North Americans, can sometimes be joyfully accessed in this manner. (For a succinct introduction to her work, check out Birgit Beumer’s obit on Sight and Sound’s web site; for more detailed information, go to Jane Taubman’s books on Muratova and her 1989 masterpiece The Asthenic Syndrome.) Despite the overflowing richness and formal inventiveness of her mise en scène, editing, and employments of sound, I suppose what puts some viewers off about Muratova’s work is the comic and often caustic hysteria of her style in capturing our troubled zeitgeist, including dialogue that is as often shouted as spoken, the ostentatious mugging of her talented actors, her preoccupations with social class and death (with corpses frequently used as tragicomic props and/or plot devices), and maniacal repetitions of phrases and mantras. (More than once, Muratova suggests a fanatical demiurge bent on producing Eugene O’Neill’s epic, unproduceable folly Lazarus Laughed.) It’s easy enough to understand literal-minded critics steering as far away from Muratova’s transgressive work as possible, but viewers delighted to explore its giddy highways and byways — including the filmmaker’s many Russian fans, who obviously kept her gainfully employed during her extended post-perestroika run — are in for a rare treat. And shunning Muratova’s outlaw virtues also means avoiding the calm wisdom and utter lack of sentimentality lurking behind all her frenzied activity.

I first became aware of Muratova when I saw her startling and galvanizing The Asthenic Syndrome (the first post-glasnost Russian film to get banned reportedly for its untranslatable obscenities), which came near the halfway point of her filmography of about 20 films, and after a long period of mostly enforced inactivity and censorship. (You can’t currently buy this feature on Amazon, but you can find a subtitled version on YouTube.) Since then, I’ve been hunting down both later and earlier examples of her singular genius, such as Second-Class Citizens (2001, also available with subtitles on YouTube the last time I looked) and the truly demented Chekhovian Motifs (2002, available commercially), to cite two other favourites. But I had to put together my own version of Among Gray Stones (1983), which I found no less exciting, even though I discovered after watching it that Muratova took her name off it after losing control of the editing (the film is attributed to the pseudonym “Ivan Sidorov,” reportedly the Soviet equivalent of Alan Smithee). I’m not usually partial to child actors, but what she manages with the featured kids in this movie, none of whom comes anywhere close to naturalism, is never short of amazing. (She’s fond of animals, too, but as far as I can tell, she usually doesn’t try to control them.)

If you can’t cope with the task of drumming up your own subtitles for this deviant adaptation of a late-19th-century children’s book, you might want to hunt down an NTSC DVD of Dva v Odnom (Two in One, 2007), which comes with English subtitles in spite of its Russian title. The film’s first hour busily unfolds around the backstage body of a suicided actor, which is eventually joined by a second corpse, while the second hour is devoted to the play that was supposedly being prepared—except that, as with a Busby Berkeley number, much of it couldn’t happen on any theatrical stage. This is a curious farce in which a middle-aged, tyrannical grump uses his sequestered, dancing-doll daughter as a pimp to snag a blonde beauty on the street for him; once she’s inside, the blonde (Renata Litvinova, a Muratova regular since the mid-’90s who also scripted this second half of the film) then employs various delaying tactics to counter his sexual moves while laughing mirthlessly and consuming his caviar. Three other Muratova films on NTSC DVDs with English subtitles that can be found most readily under their Russian titles: Korotkie vstrechi (Brief Encounters, 1967) her first feature, which Muratova co-wrote and in which she co-stars; Tri istorii (Three Stories, 1997); and Nastroyschik (The Tuner, 2004). I didn’t fancy these as much as the ones already cited when I saw them years ago, but maybe second looks would change my mind. (And if Muratova isn’t your idea of the best way to get through an apocalyptic plague, proceed directly to openculture.com/freemoviesonline for about 1,500 other options — or to subtitled films on YouTube and elsewhere by the no less giddy but far more mainstream and sometimes kitschy features of another Russian master director worth exploring, Mikhail Kalatozov, who did for running something deliriously akin to what Max Ophüls did for walking.)

***

Reading Adam Begley’s Houdini: The Elusive American in Yale’s Jewish Lives series finally got me to sample Kino’s three-DVD collection Houdini: The Movie Star, which includes one four-hour serial (The Master Mystery, 1919), three subsequent features, and a good many extras. But sample is all I could bring myself to do, because, as Begley aptly points out, “with hindsight it’s obvious that the medium itself was a disaster for an escape artist, for the simple reason that in a cleverly edited action sequence anybody could ‘pull a Houdini’….As the audience caught on to the possibility of trickery…it became glaringly apparent that the magic of the moving picture killed the magic of the escape artist.” In any case, as Begley cautions us at the outset, he’s more interested in why Houdini’s stunts were popular than in how he pulled them off, yet insofar as he mainly fails to satisfy my own curiosity about this matter, it’s his own elusiveness that finally registers the most. And the Houdini films themselves only register as a footnote to a footnote.

***

In retrospect, I’m amazed that it took me 20 years and a Criterion Blu-ray to get myself to resee Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000), a nervy encounter with the American minstrel tradition that has the audacity and good sense not simply to castigate it, but also to resurrect it and even perversely honour it by trying to put on a good show with it. As critic Ashley Clark points out in his essay, Lee even underlines this complex and dialectic effort by presenting his minstrel TV show as slickly as possible, and in his dialogue with Clark he can’t hide his amusement at the way white viewers try to decide whether it’s okay or not to laugh at the show’s racist gags. Even if I find it irritating that Lee has to shovel in so much of A Face in the Crowd (which I still halfway like for its liberal hysteria) and Network (which I still detest for its right-wing hysteria) rather than trust entirely in his own vision and strategies, I can only applaud his idea of absorbing and replicating the language of the enemy in order to understand it better.

Nevertheless, having also just previewed Noel Lawrence and Darius James’ side-splitting and ingenious Sammy-Gate, which does with (and to) ’70s media hype and graphic delirium what Bamboozled does with (and to) minstrelsy, I have to express my conviction that not even Lee’s subversion can hold a candle to James and Lawrence’s creative irreverence and inspired political incorrectness, which deserves (but probably won’t get) every bit as much critical attention. Even though Richard Beatty looks even less like Sammy Davis Jr. than Philip Proctor looks like Richard Nixon, the visual, aural, and verbal invention of James (co-writer) and Lawrence (director and co-writer) in profiling racial dementia more than makes up for these shortcomings. (And come to think of it, I never entirely believed in Damon Wayans’ uptight protagonist in Bamboozled either.) Sammy-Gate’s wild wit got me to order James’ recently reprinted and even wilder Negrophobia: An Urban Parable, a 1992 novel in screenplay form that shows both how the bracing corrosiveness of William S. Burroughs can be put to contemporary use (e.g., “a gush of his brain pulp flies by”), and how James was already anticipating Lee’s bamboozlements during the previous decade: “Nowhere is it written Black people cannot take back the images of racism and use them as a weapon against those who oppress them.”

***

As if by way of current illustration, consider the beautiful way the camera circles and then approaches Paul Robeson’s Joe in affectionate close-up as he starts to sing “Ol’ Man River” on Criterion’s wonderful new Blu-ray of James Whale’s 1936 Show Boat. It’s impossible to parcel out precisely or coherently how much this glorious moment is attributable to Robeson, Whale, the cinematographer, Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein II, the racial/racist underpinnings of the character and song, or the strength of Robeson in refuting and/or embodying and/or transcending them. In Gary Giddens’ accompanying essay, after noting that Kern was inspired to write “Ol’ Man River” after hearing Robeson speak, and before calling this “one of the supreme moments in musical cinema,” he persuasively argues that “Joe is supposed to be lazy, shiftless, but we never believe that. His very presence suggests a moral center, exuding energy and responsibility.”

There’s also no doubt that all these disparate elements play a role in forging the singular yet collective ’30s alchemy of their fusion in a politically incorrect but socially powerful and profoundly human gesture of both lament and celebration. And this is soon followed by “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” an even more radically progressive number that literally celebrates minstrelsy in everything but blackface while factoring in heaps of patriarchal sexism to boot (which it assigns to a natural order: “Fish gotta swim, birds gotta fly…”, so naturally pickaninnies are born to be exploited by their mates), meanwhile enlisting Robeson and Hattie McDaniel along with Helen Morgan and Irene Dunne in both its articulation and its appreciative approval. Those who can’t countenance such ambiguities and multilayered ironies are every bit as unlucky as those trying to suppress, deny, or avoid Huckleberry Finn (a profound example of literary minstrelsy, among other things) for similar reasons.

***

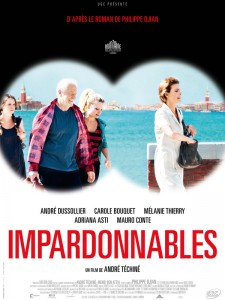

I can no longer recall whether this happened while I was teaching at the University of California’s San Diego campus in 1977 or while I was teaching at its Santa Barbara campus in the mid-’80s, but whenever I was put in charge of programming a mini-retrospective of Robert Wise films to prepare for his visit, I wound up bonding with him at a pleasant seaside dinner over the fact that one of the movies I selected was This Could Be the Night (1957), a small-scale comedy-drama in black-and-white CinemaScope about a schoolteacher and Smith graduate (Jean Simmons) who moonlights as a secretary working at a nightclub run by Paul Douglas and Anthony Franciosa. Wise seemed fond of this modest movie for the same reason I was — its low-key sweetness and its feeling for community, much of it embodied in what remains my favorite Douglas performance — so I was grateful to come across a letterboxed version at ok.ru, a newly discovered site that might be described as a Russian version of YouTube, along with many other treasures such as Robert Bresson’s Une femme douce (1969), Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Puppetmaster (1993), and André Téchiné’s Impardonnables (2011). Lamentably, you can’t find the Bresson film with English subtitles nor the Hou film correctly letterboxed elsewhere, but you can access the lovely and neglected Téchiné film — a warm symphony of familial/sexual/emotional dysfunction with André Dussollier, Carole Bouquet, and Adriana Asti, set in and around Venice — for $3.99 on Amazon Prime, where you can also watch This Could Be the Night letterboxed for $1.99.

***

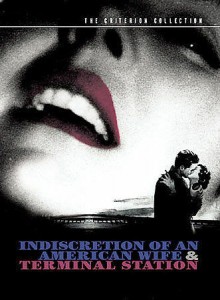

It’s both predictable and offensive that Amazon Prime members can watch Indiscretion of an American Wife (1953) — the 72-minute David O. Selznicked version of Vittorio de Sica and Cesare Zavattini’s 89-minute Terminal Station — for free, but have to pay $3.99 to rent the original. Similarly, although Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray offers both versions, it’s the Selznick skim job, complete with middle-class moral judgment built into its prudish title, that gets the star billing, while the longer version gets palmed off as a bonus. (One advantage to accessing Indiscretion on Amazon Prime is that this spares you the boredom and embarrassment of the added eight-minute “prologue,” consisting of Patti Page singing a couple of awful songs to put you in the proper mood of wistful cultural imperialism, leaving you with a 64-minute feature as a chaser.)

Even so, after shuttling back and forth between the much-condensed American version on my laptop and the longer Italian version on a much bigger home screen, I have to admit that the former at least has the merit of establishing the narrative setup far more briskly and economically, with less superfluous “atmosphere.” Otherwise, even though both versions start with the viewpoint of the heroine (Jennifer Jones) and end with that of the hero (Montgomery Clift), the Selznick release, as its title suggests, seems shaped to address its target audience more exclusively, thus spending less time with Clift when the characters are separated. (I wonder, incidentally, how readily Italians could or can accept the premise of Clift playing an Italian teacher with an American mother; I certainly couldn’t.) I also should confess that the film’s bombastic excesses in both versions — all the way down to its strenuous nods to the previous year’s High Noon(many cutaways to close-ups of clocks) in its closing stretches — only increased my admiration for the Bressonian minimalism and delicacy of David Lean and Noël Coward’s Brief Encounter (1945) in playing out its own adulterous uncertainties in another train station. Another interesting parallel between the films is that both were at least partly scripted (and very well-scripted) by gay dandies — Truman Capote is credited with Indiscretion/Terminal’s strangled dialogue — both of whom clearly understood a thing or two about clandestine relationships.

***

In closing, let me propose two superb, unsold black-and-white half-hour TV pilots from the 1950s that would make swell (and, I imagine, quite profitable) DVD releases if some company would take the trouble of chasing down the rights. The better-known of these, Orson Welles’ comic and innovative The Fountain of Youth (1956), adapted from an acerbic John Collier story, co-stars Dan Tobin (the gay-baited schoolteacher in The Other Side of the Wind) and Joi Lansing (the blonde who gets blown up in the opening scene of Touch of Evil) and suggests an entire alternate history that TV storytelling might have taken. Samuel Fuller’s lesser-known Dogface (1959) anticipates the emotional conflicts deriving from the notion of a killer canine in Fuller’s White Dog (1982) within a wartime context, with comparable moments of Griffith-like tenderness via close-ups and very physical action via brittle cross-cutting. In form as well as content, the Welles pilot is so weird that it isn’t too hard to figure out why it wasn’t sold; I’m less sure about Fuller’s parable, apart from the fact that it manages to spell out the philosophical paradoxes of war effectively enough to be fairly upsetting. I can’t/won’t tell you how I managed to see Dogface, but you can purchase a copy for $12 from DVDLady.com. The only online copy of The Fountain of Youth is an exceedingly crummy one; the late, great Gary Graver used to show his excellent 16 mm print, but I don’t know who inherited it.