An “En movimiento” column for Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. This is the original, longer version, before I had to trim it down to suit the magazine’s new design and format — J.R.

It’s logical and inevitable that the meanings of films change over time. After all, we’re the ones who determine, discover, and/or describe those meanings, and it’s obvious that we and our understandings change over time. At some point during my first decade, I saw a film in which poisoned biscuits played some role in the plot, and during a trip with my parents soon afterwards, I refused to eat biscuits in a hotel restaurant. I’ve subsequently been unable to remember or otherwise pinpoint the title of this film, even after several Google searches, but I’m sure that if I could resee it today, I wouldn’t take it as a practical warning about consuming biscuits.

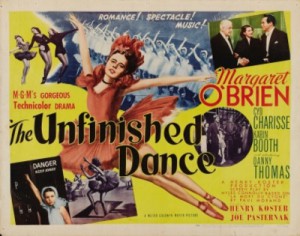

I’ve had better luck in finding and revisiting another film that upset me during my early childhood. A protracted search in this case eventually yielded The Unfinished Dance (Henry Koster, 1947), which I most likely saw at a revival in my hometown in Alabama circa 1949 or 1950, when I was six or seven, and didn’t see again until over six decades later, after ordering a DVD. What terrified me then wasn’t the film as a whole (a lush but depressing Technicolor MGM musical mostly devoted to ballet) but a single scene, which was the only thing I could recall years later: a child ballerina (Margaret O’Brien), hiding guiltily in a theater’s dark and crowded basement prop-room at night, screaming in terror when she sees props representing the Devil lit by the flashlights of adults looking for her.

This is the second time we see her frightened by this Devil, previously seen by her (and by us) as an actor in make-up in one of her dance performances. If we’d seen The Unfinished Dance after Meet Me in St. Louis (Vincente Minnelli, 1944) — which wasn’t the case for me — we probably knew that what was most distinctive about Margaret O’Brien as a child actor was her skill as a tragedian in expressing fear, rage, despair, and remorse, all of which she brings to this film as well. And I suspect that part of what unnerved me as a child was this skill, combined with my own experiences in wandering through the dark recesses of my own family’s movie theaters when they were closed.

Another part of what shook me must have been the narrative context that made this explosive scene so potent in moral terms. Introduced as a character who ”loves too much,” O’Brien plays Meg, a virtual orphan who worships Ariane, a ballerina played by Cyd Charisse, and remains so obsessively devoted to her that after a rival ballerina, Anna (Karin Booth), joins the ballet company and threatens to outflank Ariane, Meg contrives to sabotage Anna’s public performance of “Swan Lake” by extinguishing a spotlight, inadvertently opening a trap door in the process; Anna falls through the opening, and her offscreen injury ensures that she can never dance again. Along with further and related plot complications, this leads to Meg’s massive reserves of hidden guilt that make the Devil’s cackling head so confrontational. Even though this film is a remake of Jean Benoit-Lévy and Marie Epstein’s 1937 La Mort du cygnet, it wallows in the Freudian and psychoanalytical poetics of repression characteristic of 1940s Hollywood — especially films that seem to unfold exclusively in interiors that register like mental spaces. Even the few street scenes reek of studio soundstages, and the basement setting of the scary Return of the Repressed scene, like the climax of Psycho, feels exclusively like the inside of a tormented brain, condensed into a scream. Yet the remainder of the film seems largely phony and hollow, so it’s no wonder it was the first Joe Pasternak production to lose money, with an unconvincing happy ending of forgiveness and reconciliation that makes things even worse.