Written for the 99th issue of Trafic (Fall 2016) — a revision and slight expansion of two previous essays. — J.R.

The rapidly and constantly expanding proliferation of films and videos about cinema is altering some of our notions about film history in at least two significant ways. For one thing, now that it has become impossible for any individual to keep abreast of all this work, our methodologies for assessing it as a whole have to be expanded and further developed. And secondly, insofar as one way of defining work in cinematic form and style that is truly groundbreaking is to single out work that defines new areas of content, the search for such work is one of the methodologies that might be most useful. In my case, this is a search that has led to considerations of two recent videos by Mark Rappaport: I, Dalio — or The Rules of the Game (2014, 33 minutes), and Debra Paget, For Example (2016, 37 minutes). Both are highly personal works that also define relatively new areas of on-film film analysis, forms of classification that can be described here as indexing.

Rappaport was born in New York and he lived and (mostly) worked there until he moved to Paris in 2005, although his work with found footage started over a decade earlier with Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (1992), followed by Exterior Night (made in Germany for German television in 1993), From the Journals of Jean Seberg (1995), The Silver Screen: Color Me Lavender (1997), and his 2002 short John Garfield. Since his move to Paris, he has published a collection of his (fictional and non-fictional) essays in French (Le Spectateur qui en savait trop, translated by Jean-Luc Mengus, Paris: P.O.L, 2008) and three online collections in English available in Kindle editions on Amazon: The Moviegoer Who Knew Too Much (2013), (F)au(x)tobiographies (2013), and The Secret Life of Moving Shadows (available in two parts, 2014). He has also exhibited photomontages in New York, Paris, and elsewhere over the past several years — and it should be added that his interests in the Victorian novel (which he studied at Brooklyn College), melodrama, and art history have informed much of his work, from his nine features made in New York to his more recent short videos (Becoming Anita Ekberg, 2014, The Vanity Tables of Douglas Sirk, 2014, Our Stars, 2015, The Circle Closes, 2015, and the aforementioned I, Dalio, and Debra Paget, For Example, 2015, all made over the past three years).

Some of these videos, including I, Dalio, adopt the form of fictional autobiography that Rappaport used in Rock Hudson’s Home Movies and From the Journals of Jean Seberg — employing actors who play the eponymous subjects recounting their careers (exclusively offscreen, by Tito de Pinho, in I, Dalio, speaking in English with a French accent) and commenting on clips from their films. The comments, all written by Rappaport, allow the actor’s stand-in to serve as a kibbitzer (a Yiddish term for a commentator whose remarks are most often uninvited and irreverent) on the clips while pretending to be Hudson, Seberg, Ekberg, Dalio, or Paget, and they frequently match the novelistic methodologies of his fictional essays by using fiction to broaden as well as dramatize Rappaport’s analysis, sometimes creating in effect conversations between Rappaport and the films he discusses. And indexing certain roles and performances by these actors to make certain points is the most common procedure. Thus Hudson’s closeted homosexuality and Seberg’s ambiguous “blank” expressions, seen cumulatively over several roles and films, become the basis for social critiques and, in the case of Seberg, a certain amount of film theory tied to the famous “Kuleshov experiment”. In the case of Marcel Dalio — born with the name Israel Moshe Blauschild in Paris’s main Jewish neighborhood in 1900 — this becomes the basis of indexing Dalio’s mainly unsympathetic roles in prewar French cinema, which are plausibly shown to be cumulatively and implicitly (if not always individually) anti-Semitic: “In the French films of the 30s, I play every kind of scoundrel, and I’m called every name imaginable — except one.” Significantly, the two exceptions discussed are Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion (1937) and La règle du jeu (1939), where he plays sympathetic aristocratic Jews, explicitly identified as Jewish. But then, after the Nazi occupation of France forces Dalio to emigrate to the U.S., we discover that his Hollywood roles are subject to a different kind of typecasting in which his Judaism becomes both irrelevant and ignored and he becomes stereotyped simply as “French,” most often in comic and whimsical parts.

After we see Dalio playing a hotelier named Frenchy in To Have and Have Not (Howard Hawks, 1944), we hear his stand-in say, “I was no longer the ‘Jew’ with quotes around it. No one cared about that anymore. Now I was simply The Frenchman. The rules of the game suddenly changed. It was that easy. It just depended on where you were and who was defining you.” But this provocative conclusion is by no means all of I, Dalio; Rappaport also traces briefly the screen careers of Dalio’s three wives (two in France, one in the U.S.) and his returns to Europe after the war (occasioning some reversions to being cast as more unsavory types), the less apparent Jewish identities of some of French colleagues and costars (such as Jean-Pierre Aumont and Simone Signoret, who didn’t, like him, wind up on Nazi posters representing “typical” Jews — although Rappaport gets to imagine what such posters would have looked like), and other diverse tangents and asides that emerge from rummaging through Dalio’s filmography. Yet the unifying thread is Dalio’s separate personas in French cinema and Hollywood, and many mitigating factors are brought into the discussion. “Paradoxically, the French respected me more, and I almost always got a full film credit (illustrated by several clips,) even for a small role,” while a scene in the 1960 Hollywood musical Can-Can shows Dalio, “a Jew who fled Hitler,” with two other stereotypical French actors, Louis Jourdan, “[who] fought in the Resistance,” and Maurice Chevalier, “who did not resist very strenuously”. The fictional Dalio then remarks, “You might well wonder what we talked about between takes,” and the real Dalio (still in Can-Can) replies, “I’m not allowed to tell, sir.”

This is shortly followed by the observation, amply illustrated, that “A Frenchman in America can play a priest, a Jew in France cannot.” And finally, with the onset of old age, “I was no longer a type. I was neither Frenchy nor a devious Jew. I was just an old man.” And then back in France, in 1973, ten years before his death, he plays Rabbi Jacob in a hit comedy.

This, in short, outlines the new areas of “content” created as well as discovered by Rappaport while indexing the found footage of Dalio’s filmography, which also includes the effacement of his name from the credits and/or the effacement of his actual presence (as a Jew) in two 1938 French features when these were rereleased in Nazi-occupied France. And the obvious virtue of using film rather than prose to handle this material is that it proves Rappaport’s points through concrete demonstration. (For the same reason, Rappaport fictional and non-fictional essays often make integral uses of illustrations.) As Godard once said to Pauline Kael in a public discussion,

(…) the image is like evidence in a courtroom. For me, making a movie is like bringing in evidence… That’s why I’m not working in criticism anymore these days—practically—because there words always come first… To me, a good review, good criticism (whether it is in Cahiers du Cinéma or Film Comment) would be trying not to say ‘I don’t feel’ ‘I don’t see it the way you saw it,’ but, rather, ‘Let’s see it, let’s bring in the evidence’ (Godard & Kael, 1982:175-176).

Rappaport’s own biography makes him ideally suited to index Dalio’s work in this manner—not only because his own move from the U.S. to France predisposes him to observe differences in their two mainstream cinemas, but also because living in Paris clearly gave him access to a good many European films that wouldn’t have had otherwise.

***

Mark Rappaport and I have been friends for well over three decades. He’s a year older than me, and even though our class and regional backgrounds differ, we’re both film freaks and film historians who grew up with the same Hollywood iconographies, for better and for worse. How these experiences might qualify as better or worse have been the source of countless friendly arguments, all the more so when they converge on the same objects of fascination—as the title of his latest video puts it, Debra Paget, For Example.

Thirty-six minutes and thirty-six seconds long, this juicy video about the 15-year screen career of Debra Paget (1948-1963, ages 14 to 29, including a busy eight-year stretch as contract player at Fox, 1950-1957) seems at times to cover almost as much material and as much cultural ground as Rappaport’s two star-centered film features, Rock Hudson’s Home Movies and From the Journals of Jean Seberg (1995). It might even be called a compendium of Rappaport’s rhetorical strategies, such as using an actor to play the star in question — as in those two features, although here only offscreen (as was also done in I, Dalio, or The Rules of the Game), with Paget voiced by Caroline Simonds — and using Rappaport’s own voice, as in another recent video, The Circle Closes. One might say that the reason why he employs two voices is what academic critics would call discursive: he has more to say, and this “more” can’t be contained within a single voice; it also wanders every which way, as many of the best essays do. And to complicate matters, these two voices aren’t so much in dialogue with one another as they are coming at us from different angles—fictional in the case of Simonds speaking as (or for) Paget, non-fictional in the case of Rappaport speaking for himself — even though the two of them share the same basic assumptions.

The voices aren’t exactly in conflict, but they nonetheless point towards a divergence of positions that seem to make the two voices necessary. Let’s call it a divided consciousness, marking a breach that I fully share with Rappaport. This divergence can be described in many different ways—e.g., as art versus kitsch, as history versus memory, as reality versus fantasy, and maybe even as theory versus practice. Here is how Rappaport himself expresses the problem, roughly halfway through the video, starting with a parenthetical digression about Maria Montez in the 1940s and ending with the Golden Calf sequence in The Ten Commandments:

“She [Maria Montez] was called the Queen of Technicolor, but that was a euphemism. What they meant was the Queen of Kitsch….But we’re less likely to scoff at present-day kitsch, or even recognize it. In fact, we often embrace it.

“If Maria Montez was the Queen of Kitsch, surely Debra Paget is the Princess of Kitsch. But let’s be careful here. One guy’s kitsch is another guy’s nostalgia.

“If you saw these movies at the right age, at a Saturday matinee or on TV when you were a kid, it would have made all the difference. And it’s virtually impossible to explain it to other people who aren’t there. You can’t argue with someone’s childhood memories. And who’s to say that kitsch — or memories — or nostalgia, and the seemingly guilty pleasures they offer — are any less valuable in film history than, say, Ingmar Bergman or Antonioni? The jury’s still out, and won’t be in for awhile. For example –”

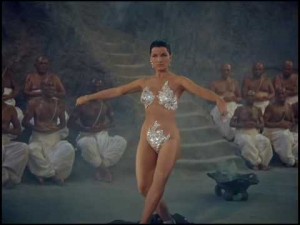

Over the three labeled sections of Debra Paget, For Example — “1. Beginning,” “2. The Middle Years & CinemaScope,“ and “3. Fritz Lang’s Indian Film/Paget’s Apotheosis”—the topics and positions towards them are indeed disparate. In the first part alone, among other things, we get Paget’s skill in walking across a room (“not as easy to do as you might think”); then we get the queasy implications of 14-year-old Paget kissing a 38-year-old Richard Conte playing a gangster, in her first screen appearance in the 1948 Cry of the City (expressed by Rappaport and then seconded by Simonds, asking, “Why is my mother allowing this?”); we hear about Paget’s mastery of “the sorrowful Madonna look” being both “a blessing and a curse”; Paget being cast in diverse ethnic parts (Italian, Native American, Polynesian); her skills as singer and dancer and her Vegas nightclub act; her playing second fiddle to Jean Peters in Anne of the Indies (1951) and her desire for bigger parts and full stardom. Then, in part two, we hear about some of the mixed blessings of CinemaScope (such as the absence of closeups, illustrated by a subdivision of the anamorphic frame into six medium shots of Debra), Elvis Presley’s marriage proposal (nixed by Paget’s mother) after they appeared together in Love Me Tender, diverse notations about Demetrius and the Gladiators and Princess of the Nile (both 1954), the latter of which gave her star billing for the first time, and much, much more.

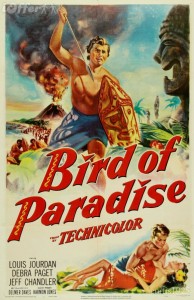

I should add that my own, equally divided psychosexual investments in Debra Paget were explored in the first chapter of my first book, an experimental autobiography called Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980, published in 2003 by P.O.L in Jean-Luc Mengus’ French translation as Mouvements: Une vie au cinéma), centering on my encounter at age eight with one of Rappaport’s own privileged sites, Bird of Paradise (1952). Oddly enough, both our encounters are tied to Judaism: In my case, Paget’s upsetting fate as a Polynesian maiden ordered to dive into a live volcano as a sacrifice for her interracial involvement with Louis Jourdan was tied in a subsequent nightmare to familial sacrifices occasioned by my older brother’s bar mitzvah. Rappaport is mostly concerned with the Jewish identities of two other actors in the movie—Maurice Schultz (as the Kahuna who orders Paget’s sacrifice), a major figure in Yiddish theater and Yiddish cinema, and Jeff Chandler (as Jordan’s American pal), born Ira Grossel in Brooklyn, Rappaport’s home town.

The reason for bringing all of this up is to point out that, to paraphrase Rappaport, one guy’s kitsch is another guy’s Judaism, and vice versa, and similarly, one guy’s bad girl is another guy’s good girl. In part two, Rappaport claims that Paget wanted more bad-girl parts like Marilyn Monroe in Niagara (1953), adding that this was what made her a star, whereas I would suggest that it was also the impossible mixture of Monroe’s bad-girl smarts and her good-girl-innocence in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes the same year—which Rappaport also quotes from, but in a different context—that did the trick. And I would further argue that Debra’s best parts all combine certain elements of saucy bad-girl irreverence with good-girl Madonna-like sorrow—even in Bird of Paradise, where she breaks the tribal taboo. But I don’t mind him bringing up Niagara because it occasions a great line to accompany a shot of the heroine’s demise (“Marilyn—frozen in a trapezoid of death”), even if this has nothing to do with Debra.

In short, we’re talking here about a terrain where friendly quibbles are inevitable, and also ultimately irrelevant. I wasn’t fully convinced that European actress Yvonne Furneaux was a dead ringer for Paget who could have played her twin, as Rappaport claims, until I happened to resee Lisbon (1956) while working on this review, which for me proves his point better than his own examples—but maybe that’s because we view both actresses differently. I can’t buy Rappaport’s claim that Paget refused to give interviews after she ended her acting career after coming across two such interviews on YouTube (both concerned in part with her faith as a Christian), but of course one gal’s acting career can turn out to be the same gal’s religion (or vice versa) years later.

Furthermore, although I’m quite happy to call Lang’s two-part Indian feature in 1959 “Paget’s Apotheosis” — even when it ushers in another long digression about Billy Daniel’s choreography (which allows for still another digression about Daniel’s boyfriend Mitchell Leisen, another Rappaport favorite) — I would personally nominate another Paget dance with a different sort of voluptuous bump-and-grind as her erotic apotheosis: namely, her burlesque, bad-girl performance of “Father’s Got ‘em” in John Phillip Sousa’s parlor in the 1952 Stars and Stripes Forever (accessible at www.youtube.com/watch?v=hwSK9u_4j6k), which allows her to sing as well as dance, with an equivalent number of shocked reaction shots. But this doesn’t make me regret Rappaport’s alternate choice, which permits him to add a riff about Paget’s revenge on a snake erection in The River’s Edge (1957), which further demonstrates that one guy’s snake is another guy’s erection (and vice versa). And even if he omits Fritz Lang’s most erotic picture (Spione, 1928) while surveying his silent films, I can readily forgive him, because he also includes ravishing bits of two other versions of The Tiger of Bengal and The Indian Tomb that preceded Lang’s own, neither of which I’d seen before.

***

A final remark about what makes Rappaport’s work cinematic and not merely an alternate form of film criticism: Let me begin with two statements made by Rappaport himself about his earlier narrative features. The first paragraph is part of a statement written by him to introduce a screening of The Scenic Route (1978); the last four come from an interview with Tony Rayns in the February 1979 Monthly Film Bulletin:

“Love, jealousy and revenge. All standard components of melodrama—but a very ‘dry’ melodrama. Expectations are thwarted and rechanneled. Instead of explanations and motivations, visual counterparts are offered. The film slides back and forth between passion and an irony which redirects it but doesn’t dilute it. A film about myths and myth-making, about the Madame Bovary in each of us, about delusions and romance in a fragile world where violence erupts randomly and unexpectedly.”

“The various elements only really fall into place when the narrations are there. The use of narration in low-budget films in general brings us back to finance; it’s cheaper and more accessible than sync-sound dialogue. But I like narration: I like the fact that you can create a discrepancy between what characters say and what you see of them. It’s something that we’ve learned from Melville, via Bresson. I think it’s an incredibly rich technique; it allows you to concentrate on essentials. Plus my mind is always full of ironic double-think…always re-assessing, always re-evaluating.

“Movies like Out of the Past and Sunset Boulevard used narration for exposition, as a device for opening the closed door, always from a single character’s point-of-view. I try to use it more centrally: what happens if you use narrations from five points-of-view?

“I once described the entire script of The Scenic Route to someone (not the truncated version that I put on the screen), and he thought it was very dry, very dehydrated. But there’s enough material there for five of the melodramas that Warner Brothers used to do! Only with all the melodramatic juices pumped out. The elements of melodrama (and of theatre) that I like have more to do with painting: it’s the gesture, the mise en scène, the lighting, the arrangement, the pregnant moment right before something happens or right after it has.

“The emotional tenor is not parody. If I’m parodying anything, it’s the fact that we can only respond to emotional situations in prescribed ways. They’re the only ways we have to respond to the trite elements of our lives. I guess it’s more a matter of irony than of parody. I rely on associations to previous things as a kind of shorthand. It’s not that audiences have to know which films I love, and I’m not interested in hommages. But it’s all retreads—human relationships have been explored, re-explored, de-explored, and yet we still respond to the grain of truth that we recognize at the heart of these situations when they’re represented on a screen. One wants the falseness to be true.”

The above can read as Rappaport’s own understanding of how he treats melodrama cinematically. And I think it could be argued that he treats his form of film criticism cinematically in the same way, at least if one replaces “narrations” and “points of view” with “critical positions” and “critical voices”—discursive avenues learned from literature and then translated into cinema. Wanting the falseness to be true is, after all, a central postulate of the cinematic experience.