Written in 2013 for an expensive book on Jacques Tati prepared for Taschen by Alison Castle. — J.R.

Jour de fête

1. A Parisian Discovers the Countryside

In 1943, Jacques Tati, age 34, was living in occupied France. He had played rugby, become a successful music hall performer, and acted in a few short comic films. That year he left Paris with a screenwriter friend named Henri Marquet in search of the remotest part of the country they could find, hoping to escape recruitment as workers in Germany. They finally settled on a farm near Sainte-Sévère-sur-Indre, located in the dead center of France — not far from where George Sand had entertained such house guests as Chopin, Liszt, Flaubert, and Turgenev — and spent a year or so getting acquainted with the village and its inhabitants.

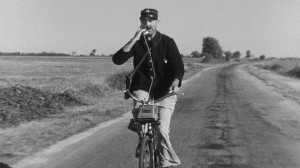

Two years after Germany’s surrender, Tati and Marquet returned to the village to make a short film, L’école des facteurs (“The School for Postmen”), in which Tati played François, the village postman, who delivers the mail on a bicycle. François was based loosely on a bit character — a befuddled postman, played by another actor — in Soigne ton gauche (1936), a comic short Tati had written and starred in. L’école des facteurs was Tati’s first directing project, and the following year he and Marquet returned with different cinematographers but the same basic crew to rework and expand the short into a feature, Jour de fête, whose brand-new color process, Thomson-Color, would make it the first French feature in color. Another writer, a professional script doctor named René Wheeler, was also enlisted.

Thomson-Color was a complex experimental process — conceived as an artisanal invention, a homemade alternative to big-studio technology — that could become France’s answer to Technicolor. Aware that he was taking a calculated risk, Tati employed two cameras — one using color and the other, for safety, using black and white — but meanwhile he designed the film’s settings with color in mind, painting many of the house doors in the village a dark gray and dressing most of the villagers in dark coats. The basic idea — part of which he carried over to PlayTime almost 20 years later — was to show a colorless village springing to life once holiday caravans arrive with carnival trappings such as painted merry-go-round horses and shiny banners, and then returning to drabness once all the festive regalia is carted away.

After Tati found himself unable to develop or print the film in color, due to technical problems with the Thomson-Color process, he eventually resigned himself to releasing it in black and white. He was unable to find a distributor for well over a year, until a successful preview in a Paris suburb inspired him to make a few more revisions, but when the film finally opened in 1949 it grossed ten times its cost and won major prizes in Venice and Cannes, helping to launch Tati’s international reputation.

The budget raised by producer Fred Orain was eighteen million francs — only about half the cost of an ordinary feature, and made possible only because Tati, Orain, the crew, and most of the cast accepted percentage points instead of fees. Once the film began to turn a profit, Tati bought back many of these shares, and it’s worth adding that about half the film’s cost was already made back in 1948 by foreign sales (including Argentina, Belgium, French Africa, and Switzerland), enabling Tati to record a new soundtrack for the English-speaking markets. This version opened to good reviews in London over a month before the French original finally opened in four Paris cinemas, in early May, 1949, two months before the birth of Tati’s second child, Pierre. (In the U.S., by contrast, the film wouldn’t open until 1952.) The initial critical reception in France was lukewarm, but Tati’s reputation steadily grew as he won over audiences — and his generally better reviews from abroad undoubtedly helped as well.

2. Casting

Tati cast some of the local villagers in a few parts — most notably, a stooped and gossipy old lady with a goat who called herself Delcassan. This character served in the film as a sort of impromptu guide and commentator on the doings of the village, addressing us directly — a bit like the stage manager in Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town, or the local sage in Fellini’s 1974 Amarcord (the latter a character who appears to have been inspired by Wilder and/or Tati). The other listed cast members who never played in any other film are Maine Vallée as Jeannette, the farm girl who flirts with the owner of the merry-go-round; a woman named Valy as Edith; and Alexandre Wirth as the young painter — a character who was added to the film when Tati produced a new version in 1964 (see section 3, below).

But most of the actors in Jour de fête qualified as seasoned professionals. The merry-go-round owner himself, Roger (interestingly named after the character Tati himself played in Soigne ton gauche), was played by Guy Decomble, who had appeared in films by Jean Renoir, Marcel Carné, and Marcel L’Herbier. The actress who played Roger’s wife Germaine (Santa Relli) had already appeared in half a dozen other French features, and Roger’s assistant Marcel was played by Paul Frankeur, who had also worked for L’Herbier and Carné (in the latter case as the police inspector in the 1945 Les Enfants du Paradis), and towards the end of his career would also figure memorably in several of the late films of Luis Buñuel[1].

3. Color and Composition

Shortly before the release of Mon Oncle Jean-Luc Godard wrote, “With him, French neorealism was born. Jour de fête resembled Open City in inspiration.”[2] But Tati’s original conception of a Jour de fête in color never fully left him. In 1964 he re-edited the film, remixed the sound track, and colored a few stray visual details with stencils. He even went back to Sainte-Sévère-sur-Indre to shoot new material involving an added character, a young artist played by Alexander Wirtz who could be seen painting some of the festivities, and went to the trouble of having his new character’s painting hand-colored on the film. And Tati was so adept at integrating this new material that the result was seamless. For the next 30-odd years, this was the Jour de fête that everyone saw and referenced.

How adding colored elements and a new character could compensate for the absence of a full-color image is an intriguing puzzle. But Tati’s compositional strategy was an intrinsic part of his genius, making him a worthy grandson of van Gogh’s framer; he was an instinctive artist with an uncanny sense of how seemingly unconnected aspects of a film could connect with one another in aesthetic terms. By an interesting coincidence, the great Danish filmmaker Carl Dreyer, who was making his final feature, Gertrud, the same year that Tati was revamping Jour de fête, and was planning to make it his own first work in color, was disappointed to discover that his production budget wouldn’t allow it, and in his case, in an effort to compensate for the loss, he commissioned a poet to write four short poems reflecting his title heroine’s inner consciousness, to introduce each of his film’s sections in a separate intertitle. Although no allusion to color is made in any of these poems, Dreyer still avowed in an interview that it was the absence of color that made them desirable, even though he later decided that these intertitles didn’t succeed as he wanted them to.

Part of Tati’s legacy is his radical rethinking of how sound relates to image — an idea his peer and contemporary Robert Bresson formulated in quite different terms. But Tati’s view of color was far more than a means of fine-tuning his images; it was part of a wider and more interactive scheme. Because he shot all his films silently and constructed his sound tracks afterward, Tati was able to create an interplay between image and sound that was never a matter of one simply reinforcing the other, and he used color more to accent the image than to enhance it. The Hollywood factory notion of applying sheets or slabs of color — which reaches a kind of apotheosis in colorizing black-and-white features — lies at the opposite end of the spectrum from Tati’s artisanal methods, in which little dabs and touches are applied as discreet counterbalances in his overall compositions of elements.

Sophie Tatischeff — who was born during the shooting of Jour de fête and later became a professional film editor — must have shared this view of her father’s approach when she returned to the color negative of this feature five years after his death, hoping with the help of cameraman François Ede to reconstruct a color print. Her understanding of her father’s conception of color also helps to explain why, once she and Ede finally overcame the technical problems seven years later, she decided to delete the character of the painter and aim instead for a restoration of her father’s original vision.

Tatischeff and Ede’s work isn’t a “pure” restoration because Tati himself was never able to edit his own color footage. But Tatischeff, who worked with her father on the editing of half of his features, was probably more qualified to carry out this task than anyone else, and she had two previous versions of Jour de fête that were edited by her father to guide her decisions. And what emerged from her work wasn’t so much a “new” Tati film as an old one seen properly for the first time, in the full flavor of its own period. In a way, this could be described as color that truly looks like 1947 — not films of that period so much as 1947 itself — and its bucolic postwar euphoria, not to mention its affection for interactive village life, has all the fragrant perfume of a time capsule. [3] Thomson-Color looks distinctly different from every other color process, and the fact that we have virtually no other color record of French life during the 40s gives Jour de fête the force of a revelation.

The full story of this restoration is recounted in a book by Ede that was published by Cahiers du Cinéma in 1995[4], a week before French release of the film in color. It recounts in many technical details a story of artisanal pride and determination triumphing over impossible odds.

4. François, Tati, and Technology

In some ways, the artisanal challenge of the color restoration of Jour de fête recalls the film itself, which chronicles the bumbling efforts of François (Tati), a slightly dimwitted but eager village postman, to approximate the streamlined technology and speed of the American postal service after glimpsing a hyperbolic French newsreel on the subject. “Hyperbolic” in fact may be putting it mildly; the part of this absurd newsreel that François glimpses maintains that “three hundred million letters a day are delivered with minimum delay” and that “the American postman, always in the vanguard of progress, now has the helicopter at his disposal” — the latter heard just before we see someone climb down an airborne ladder to a towering rooftop, and shortly before we see men in motorcycles catapulting through walls of flames in a stadium. [5]

All this goads François into trying to deliver the mail in his village as quickly as possible, with farcical results. And the old lady with the goat who serves as our informal guide eventually concludes that he’s better off doing what he’s always done rather than trying to top the Americans — cautionary words that reflect ironically on Tati’s misadventures with Thomson-Color. It’s touching to find a faint echo of this contrast in the final sequence of Tati’s last film, Parade, when two children, after the end of a circus performance, wander down to the empty stage to play with the various props, trying in their own fashion to duplicate or at least imitate the dexterity of the acrobats and other professionals.

5. Tati as Historian and as Neorealist

Chaque film de Tati marque à la fois: a) un moment dans l’oeuvre de Jacques Tati; b) un moment dans l’histoire du cinéma et de la societé française; c) un moment dans l’histoire du cinéma. Depuis 1948, les six films qu’il a réalisés, sont ceux. qui scandent le mieux notre histoire Tati n’est pas seulement un cinéaste rare, auteur de peu de films (d’ailleurs tous bons); il est, vivant, un point du repère. Nous appartenons tous à une periode du cinema de Tati: l’auteur de ces lignes appartient à celle qui va de Mon Oncle (1958: un an avant la Nouvelle Vague) à PlayTime (1967: un an avant les événements de Mai 68). Il n’y a guère que Chaplin qui, à partir du parlant, ait eu ce privilège, cette souveraineté: être présent meme quand il ne filmait pas et, quand il filmait, être exactement à l’heure, c’est-à-dire juste un peu en avance. Tati: d’abord un témoin. — Serge Daney, La rampe (Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma/Gallimard, 1983)

[Every Tati film marks simultaneously [a] a moment in the work of Jacques Tati; [b] a moment in the history of French society and French cinema; [c] a moment in film history. Since 1948, the six films that he has realized are those that have scanned our history the best. Tati isn’t just a rare filmmaker, the author of few films (all of them good), he’s a living point of reference. We all belong to a period of Tati’s cinema: the author of these lines belongs to the one that stretches from Mon Oncle (1958: the year before the New Wave) to PlayTime (1967: the year before the events of May ’68). There is hardly anyone else but Chaplin who, since the sound period, has had this privilege, this supreme authority: to be present even when he isn’t filming, and, when he’s filming, to be precisely up to the moment — that is, just a little bit in advance. Tati: a witness first and last.] [my translation]

In contrast to Daney’s “up to the moment,” meaning, “just a little bit in advance,” one should consider Jean-Luc Godard’s remark that “The cinema does not show, it previsions…when it is artisanal, it is ten or twenty years in advance; when it is factory-made, it is two or three years.”[6]

All of Tati’s work qualifies as artisanal, but there is probably no film of his that celebrates this value more than Jour de fête.

Thematically, moreover, it offers a kind of blueprint to Tati’s subsequent work, despite the fact that it offers the only rural setting apart from the middle section of Trafic. The enormous impact of the French newsreel about American postal delivery — not only on François but also on the other villagers, who mercilessly mock François’ relative inefficiency — initiates a complex and ambivalent critique of technology in general and Americanization in particular that informs the remainder of Tati’s work.

Yet the combined threat and promise of the “new” and streamlined, inextricably tied up with an ongoing internal debate about America and technology, is also discernible in the tacky and pretentious suburban architecture and household gadgets in Mon Oncle, the invading American tourists and contemporary buildings (not to mention several more silly household gadgets, seen at a trade exhibition) in PlayTime, and the all-purpose camper-trailer in Trafic. Even here, the role of American culture is already apparent in the way that a romantic dialogue from an offscreen Western movie — heard in French in the 1949 release version, and in English in both the 1964 and 1995 versions — plays over the shy flirtatious looks between merry-go-round owner Roger (Guy Decomble), and villager Jeannette (Maine Vallée).

More generally, Jour de fête remains not just “a little bit” ahead of its time (according to Serge Daney) or “10 or 20 years” (according to Jean-Luc Godard’s formula) but a full half century in its perception of what mass culture and technology might mean to the quiet life of a remote village. It might even serve as a relevant commentary on the day after tomorrow.

To appreciate Tati’s ambivalence about this matter in all its complexity, one has to see Jour de fête in a specifically postwar context, where genuine gratitude toward Americans for helping to liberate France weighed against the cultural and economic bullying imposed by the Marshall Plan — which included a quota of Hollywood pictures, some of them in Technicolor. And late in the film, a furiously cycling François manages to run two American MPs off a country road by pretending to bark orders over a telephone, in a parody of the same sort of American-style efficiency that has been intimidating him for most of the picture, ever since he saw the newsreel.

6. The World as a Work of Art

The justification for [a] pretense to disengagement derives from our Victorian habit of marginalizing the experience of art, of treating it as if it were somehow “special” — and, lately, as if it were somehow curable. This is a preposterous assumption to make in a culture that is irrevocably saturated with pictures and music, in which every elevator serves as a combination picture gallery and concert hall. The question of whether we can enjoy, or even decipher, the world we see without the experience of images, or the world we hear without the experience of music, seems to me pretty much a no-brainer. In fact, I cannot imagine a reason for categorizing any part of our involuntary, ordinary experience as “unaesthetic,” or for imagining that this quotidian aesthetic experience occludes any “real” or “natural” relationship between ourselves and the world that surrounds us. All we do by ignoring the live effects of art is suppress the fact that these experiences, in one way or another, inform our every waking hour.

—Dave Hickey[7]

Formally, Jour de fete offers a rough sketch of most of the ideas Tati would flesh out in his later features (reaching their climaxes in the black-and-white Les Vacances de M. Hulot and the color PlayTime). There’s the comic interplay between foreground and background details, such as our first introduction to François the postman on his bike, dodging an invisible wasp in the background while a hay mower in the foreground tries to decode his curious zigzagging movements — until the same wasp menaces the mower a moment later, turning him from a spectator into a comic victim himself. There’s the clean detachment of the images from the sound track — the latter a beautiful and highly selective blend of sound effects, ambient noises, and dialogue, comprising a kind of musique concrete — even though there’s more dialogue here than Tati would ever use again. This separation of sound from image allows for a certain counterpoint between the two, most apparent in the hilarious, aforementioned pantomime of shy flirtation between Roger and Jeannette to the accompaniment of dialogue from an American western playing inside an adjacent tent. (This flirtation recurs in various forms throughout the picture, and the fact that Roger is married gives the romantic longings a certain naughtiness that Tati would tend to omit from his later movies; in more ways than one, this is his most typically French film.)

Jour de fête amounts to a kind of stylistic manifesto as well. Most of Tati’s work derives from observation rather than pure invention, inflected by the aesthetic and poetic properties of music, painting, and dance (which is where the invention comes in); everyday details are the basic unit of this enterprise rather than incidents designed to advance a plot. This is why Tati’s films are often better appreciated by ordinary viewers than by critics and specialists, who tend to be more rigid about what films should be, storywise and otherwise. Tati’s observation is tempered and structured by an aesthetic-poetic imagination and by the perception that all of us, as critic Dave Hickey suggests, are living continuously inside a complex work of art that we call the world, and that perhaps only another work of art can teach us to appreciate what’s right in front of us.

But much of art is derived from other art as well as from observation, and it should added that the physical comedy in Jour de fête harks back to the purity of silent comedy in its grace and the beauty of its natural surroundings. There’s even a cross-eyed carnival worker who is directly inspired by Ben Turpin, and the bucolic splendor of the countryside offsetting Francois’ frantic pedaling as he makes his rounds clearly shows the profound mark that Buster Keaton’s silent cinema made on Tati’s work.

Such influences led some of Tati’s first reviewers in France to focus unduly on what was derivative about his comedy (with notable exceptions, such as André Bazin), and not enough on what made it unique in its poetry But time was on Tati’s side, and it was the village of Sainte-Sévère-sur-Indre and the village postman that would prevail in people’s minds and hearts, not the faint echoes of other times, places, and comics. And furthermore, Tati would show the purity of his intentions when he consistently refused to consider any sequels or spinoffs involving François, despite many offers that came his way. It was clear from the outset that he was interested in confronting the world, not in creating a franchise or a brand name.

[1] One of these films was Le Charme Discret de la Bourgeoisie (1972), and when I was working for Tati shortly after it came out, I recall having recommended this film to him and been somewhat confounded when he replied that Buñuel was a chap who had a made a film influenced by Jour de fête. It was only years later that I realized he most likely had been thinking of Buñuel’s 1969 La Voie Lactée, the first film in which he’d cast Frankeur.

[2] Jean-Luc Godard, Godard on Godard, translated and edited by Tom Milne, New York: Da Capo, p. 47.

[3] For comparably paradisiacal views of village life mixed with dollops of wry social criticism — in the Southern United States, in Ireland, and in the U.S. again — John Ford’s Judge Priest [1934], The Quiet Man [1952], and The Sun Shines Bright [1953] all spring to mind.

[4] Jour de fête ou la couleur retrouvée, Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma, 1995, passim.

[5] Ironically, the implied critique of French versus American mail delivery — however applicable to a sleepy village in the late 40s — was directly contradicted by my own experience of living in Paris in the early 70s, when I could practically set my watch by the three prompt deliveries made to my building every weekday and the two made every Saturday.

[6] Cited by Nicole Brenez in “The ultimate journey: remarks on contemporary theory,” translated by William D. Routt, Screening the Past, Issue 2, 1997 (http://www.screeningthepast.com/2014/12/the-ultimate-journey-remarks-on-contemporary-theory/), p. 7.

[7] Dave Hickey, “Air Guitar,” Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy, Los Angeles: Art Issues. Press, 1997, p. 168.