My column for the June 2016 issue of Caimán Cuadenos de Cine. — J.R.

One of the frustrations about living in the U.S. these days is the virtual absence of TV news, replaced by a media circus built around the omnipresence of single events — the deaths of Frank Sinatra and Michael Jackson, or, this year, the U.S. Presidential primary elections. As with most Hollywood blockbusters, these circuses are designed to screen out the rest of the world, assuming that Americans are interested in sensation more than thought and can only focus on one momentous event at a time (which means that the delighted TV pundits can ignore the rest of the world with impunity). So it’s logical that everything Donald Trump utters or tweets gets more coverage than anything said by Barack Obama and that the same sound bites from Trump and the other candidates get endlessly recycled, thumbed over, and analyzed.

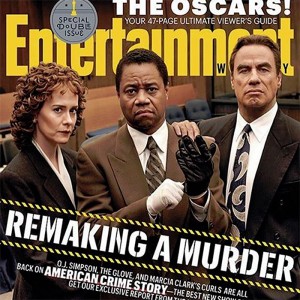

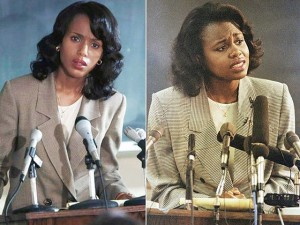

Consequently, it’s at once ironic and appropriate that the two most relevant and contemporary cinematic events that I’ve seen lately are both cable TV docudramas about media circuses of the 1990s, both of which offer certain insights into how a Frankenstein monster such as Trump was created thanks to the unholy marriage of celebrity culture and what subsequently became known as “reality TV”: a ten-part miniseries called American Crime Story: The People vs. O.J. Simpson, set in 1995-95, which recently concluded, and Confirmation, which aired a week later–a single feature about the Senate’s 1991 Supreme Court confirmation hearing for Clarence Thomas, at which a law professor and former employee of his, Anita Hill, accused him of sexual harassment.

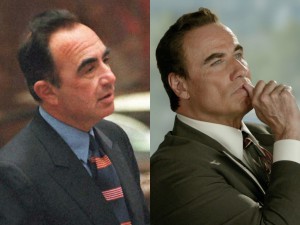

The difference between these films is considerable — the former is more accomplished, and the latter problematically mixes fictional re-enactments with actual 1991 news reports (and, even more dubiously, positions the public humiliation of Hill as an inspirational “happy ending” by implying that she became a martyred trail-blazer for a saner future). But the parallels between them and the events they cover are striking. Both events arguably culminated in huge miscarriages of justice — a murderer found innocent, a conservative sex harasser appointed to the Supreme Court — prompted by media circuses in which charges of racial brutality theatrically displaced the other issues. (O.J. Simpson, his most vocal defense attorney, and the associate prosecutor were all black, and the murder victims, including Simpson’s wife, were both white; Thomas — also married to a white woman — and Hill were both black, and the Senators at the hearing were all white.) Simpson’s defenders won his case by shifting the trial’s focus from the overwhelming evidence pointing to Simpson as murderer to the racist practices of the Los Angeles police department (which paradoxically had little relevance to this case due to Simpson’s celebrity and wealth); Thomas denied all of Hill’s sober and soft-spoken charges and overpowered them rhetorically by calling the proceedings “a high-tech lynching,” providing the event with its best-remembered sound bite.

Recounting either the news or recent history in the form of sound bites is a treacherous activity that invariably leads to some form of deception. Trump’s recurring claim that he refuses to be “politically correct” implies that PC language comes exclusively from the left, a notion usually accepted without challenge. But one could easily argue that Trump’s own favorite slogan, “Make America great again,” is a PC version of “Make America white again.” By the same token, calling Obama black is a PC way of denying that he’s half white, and “Iraq war” is a PC euphemism for the military occupation of Iraq.

On the other hand, recounting the news or recent history in terms of docudrama — or more precisely, using docudrama about recent history as a way of commenting on current events — is a more fruitful activity, bringing some historical perspective to the present and thus making a critical analysis possible. This Brechtian possibility was proposed by Godard in 1962 when he said, “Today, we should show Castro and Kennedy, played by actors: Here’s the sad story of Castro and Kennedy!” From this standpoint, Kerry Washington’s performance as Anita Hill and John Travolta’s version of Robert Shapiro — the white celebrity lawyer who led Simpson’s defense — may have even more to tell us about today than Hill or Shapiro could.