The following was commissioned by and written for Asia’s 100 Films, a volume edited for the 20th Busan International Film Festival (1-10 October 2015). — J.R.

This ambiguous comic masterpiece of 1999 might be Abbas Kiarostami’s greatest film to date; it’s undoubtedly his richest and most challenging. A media engineer from Tehran (Behzad Dourani) arrives in a remote mountain village in Iranian Kurdistan, where he and his three-person camera crew secretly wait for a century-old woman to die so they can film or tape an exotic mourning ritual at her funeral. To do this he has to miss a family funeral of his own, and every time his mobile phone rings the poor reception forces him to drive to a cemetery atop a mountain, where he sometimes converses with Youssef, a man digging a deep hole for an unspecified telecommunications project. Back in the village the digger’s fiancée milks a cow for the engineer while he flirts with her by quoting an erotic poem by Forough Farrokhzad that gives the movie its title, in a seven-minute sequence that figures as the film’s centerpiece, summarizing all its themes, conflicts, and power relations. (“I’m one of Youssef’s friends — in fact, I’m his boss,” the media engineer remarks smugly at one point.) It is also a sequence that both recaps and further develops Kiarostami’s preoccupations with death, darkness, and burial that inform both Taste of Cherry (1997), his preceding feature, and ABC Africa (2001), his following one.

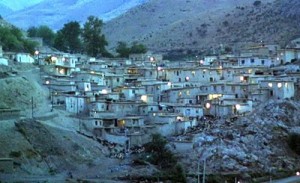

Over half of the major characters in The Wind Will Carry Us -– including the crew, the dying woman, and the digger and his fiancée –- are kept mainly or exclusively off-screen, and the dense and highly composed sound track often refers to other off-screen elements, peculiarities of Kiarostami’s style that solicit the viewer’s imaginative participation. But what’s most impressive about this global newspaper and millennial statement is how much it tells us about our world at that moment –- especially regarding the acute differences in perception and behavior between media “experts” and everyone else. Kiarostami contemplates the power adhering to class, gender, age, and education; the film reflects ironically on his own ethical relationship to the poor people he films, and it’s arguably his first since Report (1977) that tries to deal with the role of women in Iranian society. It’s also a gorgeous, Brueghel-esque treatment of landscape and architecture and a series of reflections on Persian poetry as well as animal and insect life. Arguably, one has to become friends with this movie before it opens up, but once one does, its bounty becomes limitless.