The third chapter of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2000). The cover below is that of the U.K. edition published by the Wallflower Press. To set the context, the book’s previous chapter is called “Some Vagaries of Distribution and Exhibition”. — J.R.

A much more common and systematic method of obfuscating business practices in the film industry, especially in blurring the lines between journalism and publicity, is the movie junket. Here’s how it generally works: a studio at its own expense flies a number of journalists either to a location where a movie is being shot or to a large city where it is being previewed, puts the journalists up at fancy hotels, and then arranges a series of closely monitored interviews with the “talent” (most often the stars and the director). The journalists are then expected to go home and write puff pieces about the movies in question, run in newspapers and magazines as either reportage or as a classy form of “film criticism.” If these journalists don’t oblige — and sometimes obliging entails not only favorable coverage, but articles with particular emphases set by publicists, articles that screen out certain forbidden topics and hone in on certain others — then the studios won’t invite them back to future junkets.

There are probably more of these kinds of articles about new or forthcoming movies in newspapers and magazines than any other kind, and many entertainment writers — including a number who also double as film reviewers — make a veritable profession out of these junkets. The stories that result are obviously meant to be read and enjoyed as news rather than as promotion, and most newspaper editors seem to have few qualms about fostering this false impression. It’s often standard procedure, in fact, for publicists to work directly with editors and get particular journalists assigned to write particular pieces, which means in effect that the articles are commissioned by the studios (or distributors) and then whipped into the desired shape by the editors and writers.

And it wouldn’t be fair to ascribe this sort of practice only to the big-time players in the industry; even marginal distributors sometimes get into the act as well. I was once approached by the distributor of a film by Jean-Luc Godard about writing something for The New Yorker to promote its release; the distributor had already been in touch with an editor there and was trying to set something up. Given my sympathy for the film, the offer seemed irresistible, and I obligingly sent off a letter of proposal to the editor in question. If memory serves, the final piece — which wound up as a small item in the magazine’s listings section — wound up being written by the editor himself.

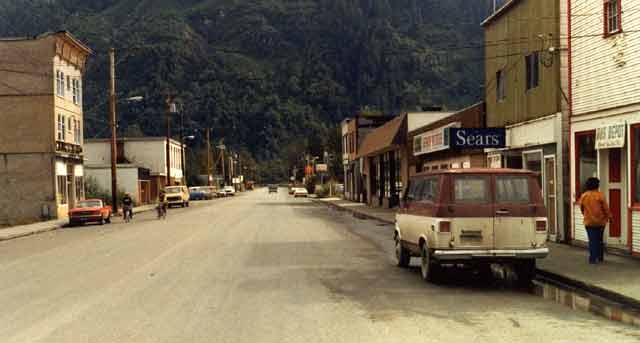

The only full-scale junket I ever participated in was in late 1981, when an old college friend who was an editor at Omni arranged for me to visit British Columbia, where John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing was being shot. The offer came almost immediately after I was fired from the Soho News, a Manhattan weekly where I had been working for over a year as a film and book reviewer — my main source of income at the time — so it was hard to turn down this opportunity, especially because I didn’t have any other easily discernible way of paying my next month’s rent in Hoboken. So I flew to Seattle in mid-December, staying over in a hotel at my own expense (with the promise of an eventual refund), then caught a 7:10 A.M. flight on Alaskan Airlines to Ketchikan. From there I took a bus to Stewart, a B.C.-Alaska border town in the cold heart of the Klondike, where I first discovered the 100-proof Canadian liqueur Yukon Jack (bottled in Connecticut) and was put up at a local motel along with the only other journalist on that particular junket, Bob Martin, who edited three teenage magazines (Starlog, Fangoria, and Twilight Zone). The next morning, we rode in the darkness up a mountain, were given special jumpsuits to prevent us from freezing, and led to the remote site where Carpenter, cast, and crew were shooting, assisted by artificial wind and snow machines to make it all look more authentic. Martin and I got to witness the explosion of a cabin and say hello to the star, Kurt Russell, but Carpenter was too busy to talk to us. This proved to be no problem as far as my article for Omni was concerned; as soon as I returned to Hoboken, Carpenter phoned me for a proper interview, and all I was expected to do according to junket protocol was pretend that whatever he said to me was said on location. (Getting my refund for the Seattle hotel room was a dicier matter until I became more aggressive about placing collect calls at odd hours to the publicist, and eventually to the producer.)

Junkets and what they produce have never been a secret, but some commentators who’ve stumbled accidentally upon them act as if they were. Even as sophisticated a writer as Time art critic Robert Hughes was shocked in the spring of 1999 when he went to see The Phantom Menace with his girlfriend’s kids and discovered that it wasn’t what the hoopla promised. Amazed at how George Lucas’s “decadence as a filmmaker resonates and, in that depressing term, ‘synergizes’ with the decadence of movie coverage in the American media,” he went on to complain in the May 16 issue of the New York Daily News:

He has managed to broker, or more exactly, enforce, a situation by which hundreds of thousands of promotional words have been churned out and published about The Phantom Menace by writers who were specifically forbidden by Lucas to see it; and the said writers went right along with it, because, in the end, the tail of Hollywood was wagging the ass, if not the whole dog, of journalism.

Though belated recognition is always preferable to no recognition at all, what seems surprising about Hughes’s outrage is the implication that if all these journalists had seen The Phantom Menace weeks in advance, they might not have written the same sort of promotional blather about it. For by bringing the entertainment press to its knees, Lucas proved that a critical reading of the movie was irrelevant to what the mass media saw as its duty. To my mind, this was no more egregious or grotesque than the front-page coverage accorded to, say, Oliver Stone’s JFK and the American Film Institute’s “One Hundred Best American Films” in The New York Times, or the kind of promotional reviews Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan received almost everywhere in the United States when they came out. Media overkill of this kind was fully operational well before The Phantom Menace was a gleam in George Lucas’s eye, so it’s possible that what made the difference for some observers like Hughes is simply that it became more obvious with the Lucas movie. After all, the same month, Newsweek ran a cover story on The Phantom Menace complaining about the media overkill while fully acknowledging that it was part of that overkill — unlike Hughes’s own magazine, Time, which simply went along with the drift.

If you’ve ever wondered where all the enthusiastic superlatives from reviewers in movie ads come from, you might be surprised to learn that many of these quotes are not extracts from longer reviews but blurbs supplied by professional blurb writers — some of whom go to the trouble of writing their own blurbs, while others actually commission blurbs from writers who attend the press screenings. It’s also been reported more than once that studios often suggest several possible blurbs to these writers and invite them to select one, apparently in order to make their job less taxing. If such practices naturally lower the credibility of film criticism as a whole, I’m inclined to regard this as a healthy rather than negative development, if only because it encourages more skepticism toward infotainment in general — an industry that, realistically speaking, includes most film reviewing as well as most so-called film journalism.

It also includes such things as TV coverage of film festivals. I’ve never attended Telluride, but I’ll never forget the national TV report on that event a few years back when members of the cast and crew of Oliver Stone’s U-Turn, including Stone, were seated outdoors in a semicircle hawking their movie and incidentally commenting on how pleasant the festival was because you didn’t have to “do” press there. This provided a Proustian flashback to a remote memory of mine from my teens in Alabama: paging through an issue of Photoplay, which my grandmother subscribed to, and coming across a photo spread devoted to Fabian’s very first date as a star without the interference or presence of any press or photographers. In point of fact, the infotainment industry has been around as long as movies, and was fully in place back in the fifties, even if it didn’t have a label back then. Whether it masks its operations any more smoothly today than it did half a century ago is debatable.

***

One of my oldest and dearest friends, Meredith Brody, is a cinephile who’s as addicted to movie lists as I am. We met at the Cinémathèque in Paris in the early seventies and usually see each other every year at the Toronto Film Festival. She lives in Hollywood and works mainly as a restaurant critic, though she also writes frequently about movies.

When I first met Meredith, she was keeping a list of all the films she saw in Paris. These days, in L.A., she keeps a kind of scrapbook devoted to all the films opening locally that she doesn’t see — pasting in newspaper ads of each of them that she later removes if and when she sees the picture.

While I was visiting her over a weekend in December 1998, she started to read aloud some of the titles in her scrapbook, all of them pasted in over the previous six months. Most if not all of these movies had played in Chicago, which meant that even if I hadn’t seen them I’d read some promotional material about them, assigned them to the second-string reviewer at my paper, and read her subsequent capsule review — or else written a descriptive capsule myself. Yet the curious and disturbing thing about Meredith’s list of titles was that whether I had seen them or not and regardless of whether or not they had shown in Chicago and I had read anything about them, a good eighty percent of them were absolutely opaque and lacking in any resonance for me, even after Meredith read aloud their ad copy.

Could this be explained by premature senility on my part, an incapacity to remember anything in my mid-fifties? I doubt it, because hearing a list of random commercial titles from the forties, fifties, sixties, seventies, or eighties wouldn’t draw the same blank from me — or from Meredith either, who’s still in her forties. (Some might argue that it’s easy to forget how many wretched movies were made during those earlier decades, when the task of furnishing theaters with product on a more regular basis made the likelihood of indifferent and unmemorable work even higher. But I’m sure I would still remember more of the lesser movies of 1956 than the bulk of the 1998 output.) The fact is, movies can get away with being terrible these days without causing any crisis in the film industry, because no matter how much the capacity to make movies that matter has been impaired, the capacity to advertise, market, and disseminate them has only improved. From a business standpoint, this is far more important than whether or not we care about these movies.

How, one may ask, could this possibly be true? If movies today have Maybe they would if the will of the people were as decisive a cultural influence as we like to believe it is, but I’m beginning to have my doubts. Much as the imposed and enforced “consensus” of the Stalinist state made it impossible to figure out what Soviet citizens really wanted until the state power was phased out — and I daresay it remains a somewhat cloudy issue today — finding out what the American public “really” thinks about movies apart from the fancies of corporate executives and journalists is no less difficult. And we can’t turn to journalism for a definitive answer because the profession is mainly devoted to spreading and running minor variations on the corporate cover stories.

Consider what might happen if Roger Ebert couldn’t find a single movie to recommend on one of his weekly shows. Or let’s assume that this has already happened once or twice. How much freedom would he have to assign a thumbs-down to everything three or four weeks in a row without getting his show canceled? And for all the unusual amount of freedom I enjoy at the Chicago Reader, how long could I keep my job if I had nothing to recommend week after week? For just as Communist film critics were “free” to write whatever they wanted as long as they supported the Communist state, most capitalist film critics today are “free” to write anything as long as it promotes the products of multicorporations; the minute they decide to step beyond this agreed-‐upon canon of “correct” items, they’re likely to get into trouble with their editors and publishers.

This isn’t to say that critics aren’t free to express their dislike for certain expensive studio productions; what they aren’t free to do, in most cases, is to ignore these releases entirely or focus too much of their attention on films whose advertising budgets automatically make them marginal in relation to the mainstream media. The fact that I’m able to do this considerably more than the majority of my colleagues is merely the exception that proves the rule, and it only applies to my writing for the Chicago Reader. The only two times I’ve appeared on Chicago’s nightly TV talk show Chicago Tonight, I’ve been forced to speak almost exclusively about studio releases. The first time, in 1994, was around the time of Oscar night; the second time was the day after Christmas two years later, and, weary of being obliged to promote only movies that were “important” because of the studio muscle behind them, I agreed to appear only if I’d be allowed to speak about a couple of foreign and independent pictures. This privilege was eventually granted to me — after a show devoted exclusively to promoting garbage like Evita — over the brief closing credits, and it’s why I’m unlikely ever to agree to appear on the show again. (1) ________________________________________________________________________________ [1] I had a much happier experience appearing on Roger Ebert’s TV show, along with fellow Chicago reviewers Dan Gire, Ray Pride, and Michael Wilmington, on a special show devoted to Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (July 17 and 18, 1999) — a film that all of us liked, in contrast to most of our New York colleagues. This experience confirmed my suspicion that network television is paradoxically more open to alternative points of view than PBS. Although the issue of speaking about independent and foreign films wasn’t relevant in this case and the constraints of the show’s format clearly limited what we could say, I did feel that the final editing of Ebert’s show fairly and accurately represented what we said during the lengthy taping. There was certainly no sense of being censored, as there has been in all my dealings with Chicago Tonight.

No less typical was the refusal of The New Yorker to give even capsule reviews to either Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man or André Téchiné’s Thieves, two of the most important U.S. releases of 1996 — and, coincidentally, the two movies I wanted to discuss but couldn’t on Chicago Tonight because prime time had to be reserved exclusively for the forgettable “big” movies of the moment, no matter how awful. (Such restrictions can lead to a lot of wishful thinking: one colleague on the show explained how Evita reminded him of Bertolt Brecht.)

The reasons for the neglect of these two features in The New Yorker are probably not identical, apart from the fact that in both cases they weren’t deemed important enough by its film reviewers. Dead Man was distributed by Miramax and Thieves by Sony Classics, a comparably large company. I don’t think Sony Classics could be blamed for The New Yorker overlooking Thieves — a neglect that undoubtedly has mainly to do with an overall neglect of foreign-language movies that was spearheaded by Pauline Kael during her last years as critic there but has become commonplace in virtually all mainstream magazines since then. But in the case of Dead Man, I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say that Miramax played a role in the film’s neglect, especially when one considers that this was the first of Jarmusch’s features to have been snubbed by The New Yorker in this fashion. (That it also happens to be the best of Jarmusch’s features, in my opinion, is a point worth arguing.) As soon as it became apparent that Jarmusch, protected by his contract and by his ownership of the film’s negative, refused to allow Miramax to recut Dead Man for its American release, the distributor’s lack of enthusiasm for the film became obvious, and manifested itself in a number of ways. When, for instance, the programmer of a Jarmusch retrospective contacted Miramax about showing the film, he was advised not to because it was lousy. Jarmusch himself publicly denounced Miramax’s handling of the film when he accepted an award for Robby Müller’s cinematography at the New York Film Critics Circle’s annual dinner, and was subsequently supported in his protest at the same event by Albert Brooks — who had dark stories of his own about how his own first feature, Real Life, had been handled by its distributor.

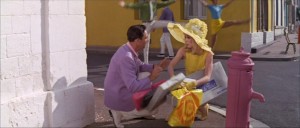

A good example of the sort of film Miramax puts its muscle behind is The Wings of the Dove; among the major films it has chosen to dump over the past few years even more flagrantly than Dead Man are Abbas Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees, the color version of Jacques Tati’s Jour de fête, and the restoration of Jacques Demy’s The Young Girls of Rochefort. The fact that The Wings of the Dove was treated with vastly more respect and attention by the national press than any of these pictures — which implied that a softcore, middlebrow reduction and distortion of a late Henry James novel was vastly more important than key works by four of our greatest filmmakers — was almost entirely a function of the message sent out by its distributor, both in terms of advertising dollars and in terms of overall handling. The insulting implication that this emphasis accurately reflected the taste of the public is of course impossible to prove (or disprove); to say that Miramax’s campaign “worked” on the public as well as on the critics doesn’t mean that a comparable campaign on behalf of the color Jour de fête wouldn’t have worked as well, even if the targeted audience would have been substantially different.

From the vantage point of Chicago, Jour de fête and The Young Girls of Rochefort received limited runs only because the Music Box, the principal independent Chicago art theater showing foreign-language pictures, made repeated requests to show them; when Miramax finally agreed, it stipulated that no money be spent advertising these pictures. In the case of Through the Olive Trees, which received an even more limited run at the Art Institute’s Film Center, no advance screenings for the press were permitted and even requests for videos for preview purposes were denied. Is it any surprise, therefore, that none of these three pictures was reviewed on Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert’s TV show? The fact that Disney owns Miramax and produced the Siskel-Ebert show might prompt conspiracy theories about this process, but in fact no conspiracies are necessary to explain this neglect. (On other occasions, I should add, Siskel and Ebert went out of their way to support relatively independent efforts such as Jon Jost’s All the Vermeers in New York.) Miramax has the clout to dictate which of its releases are important and which are not, simply due to a radical failure of nerve, imagination, knowledge, and intelligence on the part of magazine and newspaper editors, TV producers, and reviewers — none of whom expect to be called on their decisions because these are virtually invisible to the public.

The whole notion of expertise in film criticism is cripplingly tautological: according to current practice in the United States, a “film expert” is someone who writes or broadcasts about film, full stop, yet most “film experts” are hired not on the basis of their knowledge about film but because of their capacity to reflect the existing tastes of the public. The late Serge Daney understood this phenomenon perfectly —and made it clear that it was far from exclusively American — when he remarked that the media “ask those who know nothing to represent the ignorance of the public and, in so doing, to legitimize it.”

Case in point: Chicago film critics who often attended the same screenings as Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel were aware that the former is a hardcore film buff and the latter, who died in early 1999, was someone whose interest in film, at least to all appearances, was almost exclusively professional. (When Siskel first started writing for the Chicago Tribune, his main beat was real estate.) For instance, Ebert attends several film festivals every year and Siskel generally made it to few or none. After attending Cannes only once, as a TV reviewer in 1990, Siskel showed no interest in returning, and one could surmise that his relatively low recognition factor abroad might have been partially to blame. Ebert reviews a good many film books, and to my knowledge Siskel never did; if he ever read any books about film on his own, it would have surprised me. Inside the profession, Siskel was famous for making so many gaffes about movies in his weekly print reviews that Neil Tesser in the Chicago Reader used to run a weekly feature that inventoried them, entitled “Siskel Watch,” long before I came to Chicago; later, I was told Siskel’s mistakes became fewer after his copy began to be regularly and extensively checked by others.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that I wound up agreeing with Ebert’s judgments more than Siskel’s on their TV show. Gene’s own strength was a commonsensical approach based on his own extensive experience as a reviewer, and it often served him well. But if one mentioned the discrepancy in backgrounds, orientations, and apparent interests between Siskel and Ebert to a nonspecialized viewer of their show — noting simply that one of them was clearly an enthusiastic film buff while the other just as clearly wasn’t — the most common response was to query which one was the enthusiastic film buff. In other words, though I regard Siskel and Ebert as the best by far of the TV reviewers, the show’s format made it virtually impossible to recognize informed opinion or expertise; matters of film history and aesthetics were virtually beside the point.

So it wasn’t surprising to hear it said of Siskel, shortly after he died, that he “loved movies” — an assertion made on the cover of TV Guide, by Whoopi Goldberg on the 1999 Academy Awards telecast, by Janet Maslin in the New York Times (whose own disinterest in movies, apart from the movie business, may even surpass Siskel’s), and in many comparable places and circumstances. If in fact he did love movies independently of his professional duties, he did a superb job of hiding this fact from his colleagues. The only extended conversations I ever had with him were on the subjects of Anita Hill (at the time of the Clarence Thomas hearings) and his own show, and I never heard about him casually discussing any movie, new or old, with any other colleague

Yet the potency of Gene’s TV profile was such that in July 2000 — five months before the new, expanded, and more prominent headquarters of the Art Institute’s Film Center, Chicago’s principal nontheatrical film venue, was scheduled to open — it was announced with some fanfare that it would be renamed The Gene Siskel Film Center. And it was equally telling that this new name was widely perceived within Chicago as a sort of cosmopolitan calling card that would make the Film Center better known outside the United States; as Tony Jones, president of the School of the Art Institute, expressed it, “We think it is a fitting tribute to Gene because he helped focus the international entertainment spotlight on Chicago.”

But did Siskel actually do that? If the Film Center’s new name makes its cultural agenda more user-friendly for a wider public, then the renaming would be justified — even if it still might foster a certain amount of confusion, as renaming the Art Institute the Entertainment Institute undoubtedly would. On the other hand, whether it would enhance the institution’s international reputation is questionable, for outside the highly circumscribed world of U.S. television, Siskel’s name is no more meaningful than that of, say, O. J. Simpson. And even within the world of Chicago, Gene was far from being the Film Center’s most faithful supporter, at least as a journalist. According to Chicago writer Patrick McGavin, Siskel reviewed only one Film Center program between 1986 and 1998 — in contrast to the hundred or so pieces done by Dave Kehr over seven years, or the 341 published by Michael Wilmington in only five years, both for the same paper.

Ebert and Siskel’s show may well have represented one of the many points in our film culture where reviewing shades off into promotion and coverage becomes more important than evaluation. Given the huge promotional budgets of most studio releases, this is probably inevitable; the furnishing of clips for a TV review or for a TV preview is not necessarily the same process, but to the untrained viewer it often looks like the same thing, and in many cases it is virtually the same thing. By the same token, the newspaper reader who can’t easily distinguish between film criticism and film promotion — between the reviews of movies and the news stories about them — isn’t so much naive as hip to what’s going on.

***

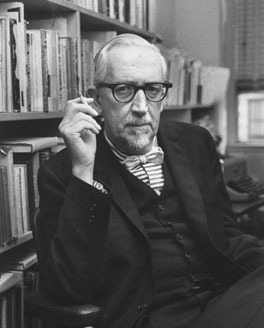

The first contemporary film critic I ever read regularly with admiration was Dwight Macdonald, who wrote a monthly column for Esquire between 1960 and 1966. I was between the ages of seventeen and twenty-three during this period, and for the first couple of those years I became friendly with one of Macdonald’s sons, Nick (who subse-quently became a filmmaker, and once persuaded me to run off to see Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game for the first time, in New York, during one of our school breaks). Towards the end of Dwight Macdonald’s stint at Esquire, when I was an undergraduate at Bard College and running the Friday night film series on campus, I invited him to give a lecture there, and spent an enjoyable evening with him.

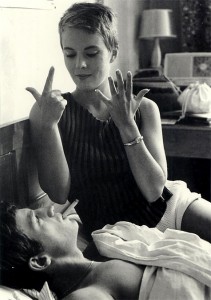

Though I can’t say I agreed with Macdonald’s taste about everything — my favorite film in the mid-sixties. F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise, bored him to tears — he provided much of my initial route into film as an art form, and I was as enthusiastic about his polemical prose style as I was about his taste and critical perceptions. Yet by the time he collected his film pieces in the late sixties, in a collection called On Movies, my feeling about his work was already becoming modified. Part of this seemed to be due to a change in Macdonald’s own positions; after all, he had essentially launched his Esquire column by heralding and defending Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima, mon amour, Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, John Cassavetes’ Shadows, and Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’avventura, and concluded his stint as a film reviewer by denouncing Resnais’s Muriel, Antonioni’s Eclipse, and Orson Welles’sThe Trial, among other films, while ignoring the subsequent films of Godard. But part of it came from a growing suspicion that Macdonald’s grasp of film history was partial and in some ways superficial.

This was eventually brought home to me by the juxtaposition of two statements in On Movies. The first, which begins the second paragraph of the book’s “Forenotes,” is, “I know something about cinema after forty years, and being a congenital critic, I know what I like and why.” The second occurs seventeen pages later, in the fourth paragraph of the book’s first essay, “Agee on the Movies.” It’s a passing remark on a letter James Agee sent him in 1927 that Macdonald has just quoted from: “’Why was movie jargon puzzling?’ [Agee] begins and proceeds to explain the ‘lap dissolve’ (which I must confess it’s taken me forty years to realize doesn’t refer to holding the camera in the lap but to overlapping; should have read his letter more carefully). . . .” (2)

_________________________________________________

2. Dwight Macdonald on Movies, New York: Da Capo, 1981, pp. 1x and 5.

Though it’s characteristically refreshing of Macdonald to cheerfully concede his ignorance about a technical term, it’s still highly revealing what his candor exposes about what’s expected from film critics, and what many film critics expect from themselves. Try to imagine, if you can, a respected literary critic at the end of his career writing, “I know something about literature after forty years,” and then confessing without embarrassment, a few pages later, “I’ve just discovered that a semicolon is something other than half of part of the lower intestine that extends from the cecum to the rectum.”

It might be argued, I suppose, that the importance of the semicolon in relation to literature exceeds the importance of the lap dissolve in relation to cinema, but even this position is somewhat debatable. I would counter that the lap dissolve is every bit as important to the work of Josef von Sternberg (a director, incidentally, that Macdonald treats fairly dismissively) as the semicolon is to the work of Henry James. [The above lap dissolve is from Sternberg’s An American Tragedy.] I would further argue that the importance of lap dissolves and superimposed images in Sunrise is fundamental to the art of Murnau in that film. This doesn’t mean that an acquaintance with the term “lap dissolve” would have necessarily altered Macdonald’s appreciation for Sunrise, but it does at the very least suggest that his objections could have been voiced in a more sophisticated and intelligible fashion.

Magazine and newspaper editors, book publishers, and TV producers seem to deem a certain basic knowledge about the medium — considered obligatory to informed writing in our culture about painting, sculpture, theater, dance, architecture, literature, history, psychology, and countless other disciplines, not to mention sports — inessential when it comes to film. Consequently, Macdonald’s passionate if imprecise engagement with cinema was every bit as unexceptional as Siskel’s “love of movies.” And both are reflected in the haphazard way in which The New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, and the Times Literary Supplement assign reviewers to books about film, which isn’t the case with books about the above subjects. (In the Times Book Review, Janet Maslin’s review of David Thomson’s Rosebud and Alexander Stille’s review of Tag Gallagher’s The Adventures of Roberto Rossellini are two examples of what I mean.)

Why? Part of the reason is that movies are regarded as a “democratic art,” which means that anyone and everyone is entitled to have an opinion about them — a position that I am not in the least bit interested in contesting, at least insofar as I believe in democratic values. But problems begin when this democratic ideal becomes confused with issues of expertise — when, in short, anyone is proclaimed an expert precisely because he or she is publicly stating an opinion. I don’t mean to suggest by this that either a Siskel or a Macdonald qualifies as an “anyone”; as I’ve already implied, both had their areas of competence as well as distinction. So do other colleagues whom I think even less of — respected reviewers who either hate what they’re doing or feel so alienated by it that they wind up writing about not what they like but what they think or assume their readers will like.

It’s clear that even alienated labor of this kind can provide helpful services to some people. But I object to turning this kind of alienation into a norm of criticism, which is what I see happening all around me — and to factoring in low estimations of the audience as a way of rationalizing low expectations on the part of reviewers. When alienation of this kind enters reviewing, a whole set of agendas apart from the movies themselves wind up determining much of the shape and drift of the critical discourse. Preconceptions set up by ads and promotional campaigns launched months in advance determine more of what the reviews say than anything in the movies themselves, and it’s often felt that the major job of reviewers should be to ratify such preconceptions rather than attempt to refute them. The following chapter examines in detail one clear instance of how this gets played out.