At Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna in the summer of 2015, Ehsan Khoshbakht and I launched a “Jazz Goes to the Movies” program, and reproduced below are our catalogue descriptions of what we showed. Late in June, Ehsan and I will be presenting a sequel to this program, with shorts featuring Duke Ellington.– J.R.

Jazz Goes to the Movies

Now that jazz is no longer assumed to be automatically synonymous with decadence and the forces of darkness, it can finally be experienced and evaluated on its own terms, and we can begin to look back on a century-long partnership of jazz and film with a certain objectivity. Both are relatively new arts roughly contemporaneous with the 20th century, having grown out of socially disreputable origins and having fought for serious recognition.

Part of this partnership has yielded the “jazz film,” a subgenre basically devoted to the recording of performances. But there are also successful collaborations between the expressive possibilities of jazz and film. And the ways in which jazz has been used in movies invariably tells us a great deal about the social, ethnic, aesthetic, and cultural biases of diverse societies and periods. The various responses of film producers to integrated jazz groups in the thirties, forties, and fifties, provide a kind of thumbnail social history. Sometimes black musicians were forced to play off-screen while white stand-ins mimed their solos and sometimes white musicians were kept in the shadows to appear black.

Perhaps the first known conjunction of jazz and the fiction film took place in the same year that the first jazz recording was made, when The Good for Nothing (1917), a now lost silent comedy showed the Original Dixieland Band. Leaping ahead to the sound film, we come upon Black and Tan Fantasy, a remarkable short made in 1929 by Dudley Murphy. Later on, while Soundies saw jazz films mass produced and turned into jukebox attractions, the dream of a “pure” jazz cinema was made reality in films made by artists with a background in animation or photography.

Some directors are more adept at using jazz than others. Directors who like to improvise on occasion seem to have a special feeling for the music. In the movies of jazz aficionado Howard Hawks, musical get-togethers between allies always have strong communal functions. Only Ball of Fire (1941) and its remake, A Song is Born (1948), use unadulterated jazz explicitly to advance the mood of fellowship in the plot, but the principle is the same in the songfests of some of his best films.

Private torments as well as collective euphoria infuse the atmospheric surfaces of such fiction films as All Night Long (Basil Dearden, 1961) and When it Rains (Charles Burnett,1995), while Bert Stern and Aram Avakian’s exuberant Jazz on a Summer’s Day (1959), a documentary filmed at the Newport Jazz Festival, finds the same euphoria in the audience as well as onstage. Finally, Big Ben: Ben Webster in Europe (Johan van der Keuken, 1967) presents a portrait of a jazz great in exile. (Ehsan Khoshbakht and Jonathan Rosenbaum)

***

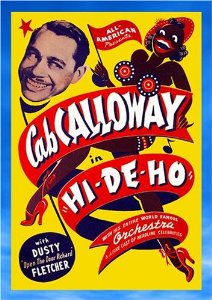

CAB CALLOWAY’S HI-DE-HO

USA, 1934 Regia: Fred Waller

Scen.: Milton Hockey, Fred Rath. F.: William O. Steiner. Int.: Cab Calloway, Edwin Swayzee, Lammar Wright, Doc Cheatham, Al Morgan, Leroy Maxey, Harry White, Eddie Barefield, Andrew Brown, Arville Harris. Prod.: Paramount Pictures

Cab Calloway is deep in sleep on a night train from Chicago when a telegram arrives from Irving Mills, asking him to change the opening number of the next day’s performance at New York’s Cotton Club. The leader wakes up the band and a jam session in pyjamas kicks off, with the band members recreating the sound of a train in motion. Upon arriving in New York, Calloway recommends to the coach attendant that he buy a radio, to keep his wife “entertained” while he is at work. When the attendant acquires the radio which promises to “bring the leading radio artists into your home”, to his dismay it literally brings a seducing Cab Calloway into his home, but only when he is away and she feels lonesome!

Subversive and erotic, this early jazz short is head and shoulders above many 1930s musical shorts in the way the storyline is developed and how it incorporates hit songs, such as the drug-charged ‘Minnie the Moocher’. A commentary on the medium of radio and the Cotton Club broadcasts, which exposed many Americans to live jazz, the film moves from reality to fantasy, with jazz making the leap smooth and fun. (Ehsan Khoshbakht)

***

TILLIE

USA, 1945 Regia: William Forest Crouch.

F.: Don Malkames. M.: Leonard Weiss. Scgf.: Sam Corso. Int.: Louis Jordan, Eddie Roane, William Austin, Al Morgan, Alex “Razz” Mitchell, Nicki O’Daniel, Richard Huey, Joan Clark. Prod.: Berle Adams.

Soundies were pre-MTV, short musical films of the 1940s shown on a special coin-operated video jukebox called a Panoram. For ten cents, the machines played a three-minute video on an 18 x 22 inch screen. Co-produced by James Roosevelt, son of the president Franklin D Roosevelt, and designed to exploit the popularity of the hit songs of the day (whether jazz, pop, novelty songs, ballads or vaudeville acts), Panorams were installed in bars, hotel lobbies and restaurants across the US and served as a temporary bridge between cinema and TV.

A typical Panoram machine contained a 16mm RCA rear projector, which would project the film in a continuous loop capable of playing up to eight different Soundies spliced together. Owing to the projection mechanism, the films were printed backwards and relied on a system of mirrors inside the mahogany covered cabinet to ensure the image produced for the viewer was correct.

The installation of 4,500 Panorams meant there was a great demand for Soundies, which were produced on both the East and West coasts. Though producers were less concerned with the quality of the Soundie than with cashing in on the popularity of an artist, the recordings documented and preserved on film some of the best jazz acts of the 1940s including Big Joe Turner, Billy Eckstine, Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, Cab Calloway, Meade Lux Lewis, Lena Horne, Louis Armstrong, and Nat King Cole.

There were also some longer films produced by the Soundie Corporation of America, such as the feature-length Pot o’ Gold (1941), which were intended first for cinemas before the musical numbers were split up into individual Soundies. Tillie is an example of a Soundie produced by cutting a longer film; it was re-edited from the two-reel Caldonia (1945) directed by Soundie specialist William Forest Crouch.

In retrospect, Soundies are notable for having captured uninterrupted jazz performances on film in the classical era and beyond – even if the music was pre-recorded and seldom live. Usually a director was assigned to film three or four Soundies in one session, like the Kiev-born Josef Berne who directed Duke Ellington shorts, and Warren Murray who made all the Fats Wallers Soundies. The scripts would usually be based around the song, with scenery and extras derived from the song’s themes, but mostly limited to a stage-like space with the performer playing directly to the camera.

The rise of TV as well as other war-time restrictions led to the demise of the Panoram and its counterparts. In 1947 the production of Soundies ceased. When they were sold to TV stations later on, for use as programme fillers, they proved to be valuable moving picture documents of jazz history for generations to come. (Ehsan Khoshbakht)

***

BALL OF FIRE

USA, 1941 Regia: Howard Hawks

T. it.: Colpo di fulmine. Sog.: Billy Wilder, Thomas Monroe. Scen.: Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder. F.: Gregg Toland. M.: Daniel Mandell. Scgf.: Perry Ferguson. Mus.: Alfred Newman, David Buttolph. Int.: Gary Cooper (Prof. Bertram Potts), Barbara Stanwyck (Sugarpuss O’Shea), Oskar Homalka (Prof. Gurkakoff), S.Z. Sakall (Prof. Magenbruch), Tully Marshall (Prof. Robinson), Leonid Kinskey (Prof. Quintana), Richard Haydn (Prof. Oddly), Aubrey Mather (Prof. Peagram), Alan Jenkins(Garbage Man), Dana Andrews (Joe Lilac), Dan Duryea (Duke Pastrami). Prod.: Samuel Goldwyn Studios.

Howard Hawks’ version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, scripted by Billy Wilder, Charles Brackett, and Thomas Monroe, isn’t exactly a jazz film, apart from one scorching rendition of “Drum Boogie” by Barbara Stanwyck (dubbed by Martha Tilton) with Gene Krupa and his orchestra (including Roy Eldridge on trumpet) — although it was eventually remade as one by Hawks himself (A Song is Born, 1948) that wasn’t nearly as good as the original. But it does give a bracing demonstration of what jazz can do to enhance a whole feature — especially in the world of Howard Hawks, where even the nicknames of various characters suggest the complicity, warmth, and camaraderie of the jazz world. The seven dwarfs in this case are seven pedantic and unworldly professors, headed by Gary Cooper and also including such comic fuss-budgets as Oscar Homolka, S.Z. Sakall, and Tully Marshall, who are compiling a dictionary of contemporary slang, and wind up getting instructed by a beautiful singer named Sugerpuss O’Shea (Stanwyck) in flight from both the police and the mob. The secondary cast includes Dana Andrews, Dan Duryea, and Elisa Cook Jr., and the cinematographer is Gregg Toland.

As one of Hawks’ best analysts, Shigehiko Hasumi, has observed, “In Hawks’ world, where inversion, exchange and repetition always ensure the dominance of women, the key issue is who will control the coincidences and not be deceived by similarities. In almost all cases, it is the men who are in the weak position and the women in the strong position,” and Stanwyck is the one who mainly triumphs in the comic complications of Ball of Fire, where inversion, exchange and repetition are employed as musically as they are in jazz. (Jonathan Rosenbaum)