Originally written as the tenth chapter of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000), this is also reprinted in my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles. Because of the length of this essay, I’ll be posting it in two installments – J.R.

Nothing irritates one more with middlebrow morality than the perpetual needling of great artists for not having been greater.

— Cyril Connolly

During my almost thirty years as a professional film critic,

I’ve developed something of a sideline — not so much by

design as through a combination of passionate interest and

particular opportunities — devoted to researching the work

and career of Orson Welles. Though I wouldn’t necessarily

call him my favorite filmmaker, he remains the most

fascinating for me, both due to the sheer size of his talent, and

the ideological force of his work and his working methods.

These continue to pose an awesome challenge to what I’ve been

calling throughout this book the media-industrial complex.

In more than one respect, these two traits are reverse sides of

the same coin. A major part of Welles’s talent as a filmmaker

consisted of his refusal to repeat himself — a compulsion to

keep moving creatively that consistently worked against his

credentials as a “bankable” director, if only because banks rely

on known quantities rather than on experiments. In industry

parlance, a relatively bankable director — someone like Steven

Spielberg or James Cameron in the present era, Charlie Chaplin

(for most of his career, up through The Great Dictator) in an

earlier era — is someone who knows how to “deliver the goods,”

which doesn’t necessarily rule out experimentation but limits it to

retooling certain tried-and-true elements. On an art-house level,

even Woody Allen remains relatively bankable because no matter

how much he experiments, most audiences still have a pretty

good idea of what “a Woody Allen movie” consists of. Welles never

came close to attaining this kind of public profile, and in terms of

his ability to keep turning out movies that played to paying

audiences, he paid dearly for this deficit. None of his pictures turned

a profit on first release in this country with the sole exception of

The Stranger, perhaps the least distinctive and adventurous item

he directed — a film made in order to prove that he was bankable,

and, because the commercial success even of that movie was only

modest, it led to no sequels. In fact, the very notion of sequels of

any kind remained anathema to Welles, and people who wonder

why he couldn’t or wouldn’t turn out “another Citizen Kane” —

including such unforgiving biographers as Charles Higham, Simon

Callow, and David Thomson — tend to overlook not only the unique

And complex set of circumstances that made his first feature possible

but also the temperamental facets of his talent that made such a

possibility unthinkable.

it’s interesting to consider that both started out in their early twenties,

both died at the age of seventy, and both completed thirteen released

features. Another significant parallel is that both wound up making all

their completed films after the fifties in exile, which surely says

something about the creative possibilities of American commercial

filmmaking over the past four decades. But in other respects their

careers proceeded in opposite directions: Welles entered the profession

at the top regarding studio resources and wound up shooting all his last

pictures on shoestrings and without studio backing; Kubrick began with

shoestring budgets and wound up with full studio backing and apparently

all the resources he needed. (1)

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] On the basis of this difference, one could argue that Kubrick succeeded in working within the system while retaining his independence on every picture except for Spartacus while Welles retained his independence more sporadically and imperfectly, and ultimately at the price of working outside the system. Yet the price paid by Kubrick for his own success — a sense of paranoid isolation that often seeped into his work, and finally no more completed features than Welles managed — can’t be discounted either.

Even though the first of Kubrick’s features, Fear and Desire (1952),

has mainly been out of circulation for the past several years, the

remainder of his work is sufficiently well known to make a recounting

of his filmography unnecessary, but the same thing can’t be said for all

of Welles’s completed features. The best known remain those released by

Hollywood studios (Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, The

Stranger, The Lady from Shanghai, Macbeth, and Touch of Evil)

and two independent features in the fifties that continue to circulate,

Othello and Mr. Arkadin. The remaining five, thanks to their

independent financing and their checkered commercial careers, tend to

be less known in the United States. In chronological order, these are The

Trial (an adaptation of the Franz Kafka novel, 1962), Chimes at

Midnight (also known as Falstaff, adapting portions of all the

Shakespeare plays featuring Falstaff, 1966 — considered by many critics

to be Welles’s greatest feature), the hour-long The Immortal Story

(an adaptation of an Isak Dinesen story, in color, made for French

television, 1968), and two rather different essay films: F for Fake

(about art forgery in general and art forger Elmyr de Hory, writer

Clifford Irving, and Welles himself in particular, 1973) and Filming

Othello (about the making of Welles’s 1952 Othello, his first

completed independent feature, 1978).

The unexpected commercial success of the reedited Touch of Evil

in 1998, discussed in the previous chapter, seems to have made Welles

relatively “bankable” again, with the result that a good many other

Welles or Welles-related projects have either just surfaced (such as

movies entitled The Big Brass Ring, Cradle Will Rock, and RKO

281) or are in the works (including possible restorations of Welles’s

The Other Side of the Wind, The Magic Show, The Deep/Dead

Reckoning, and Orson’s Bag). Yet the ideological challenge posed by

Welles’s career remains as real and as operative as ever, because it

continues to throw into question most of the working assumptions we

have about the operations of the film industry.

I’m not claiming that this challenge was always or necessarily

intentional. Though part of his ambition was to confound audience

expectations and to shock or surprise, some of his unorthodox work

habits were arrived at over the course of his unruly career rather than

conceived as deliberate provocations. In other to summarize what

these habits and practices consisted of, I’ve drawn up the following list

and tried in each case to indicate the particular received ideas about

filmmaking and film culture that they challenge (in some cases, these

six topics overlap):

I. Welles as an independent filmmaker. His first and second features,

Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, were studio

releases, both made at and with the facilities of RKO, and this

has led many recent commentators to regard Welles as an

unsuccessful studio employee throughout his career rather than

as an independent filmmaker, successful or otherwise. Insofar

as most film histories are written by industry apologists of one sort

or another, this is an unexceptional conclusion, but not necessarily

a correct one. To my mind, Welles always remained an independent

who financed his own pictures whenever and however he could, and

perhaps the only movie in his entire canon that qualifies as a

Hollywood picture pure and simple, for better and for worse, is

The Stranger. In many cases, one can easily separate his features

between Hollywood productions (e.g., The Lady from Shanghai,

Macbeth) and independent productions (e.g., Othello, F for Fake),

but the divisions aren’t always so clear-cut: the unfinished It’s All

True started out as a studio project and ended up as an

independent project; according to Welles, Arkadin in its release

form was even more seriously mangled by its producer than any of his

Hollywood films; The Trial was largely financed by Alexander and

Michael Salkind, some of whose productions (including Superman

and The Three Musketeers) can be loosely labeled as “Hollywood”

or “studio” releases; and even a clearly independent effort like Don

Quixote started out as a TV project backed by Frank Sinatra.

Part of what made and continues to make Citizen Kane exceptional

is that it was made with exceptional freedom and control and studio

facilities, and this came about because Welles refused to sign a

Hollywood contract to make pictures unless he had this control — and

because he was formidable enough as a mainstream figure in the late

thirties to demand it. People today tend to forget how much of an

anomaly Kane was as a “Hollywood picture” when it was initially

released in 1941; it took many decades of ideological spadework on the

part of critics before it was perceived as a Hollywood classic, and

paradoxically this achievement mainly came about through a demolition

job — Pauline Kael’s “Raising Kane” — that argued that, contrary to

earlier claims that Citizen Kane was a “one-man show,” made by Kael

herself as well as many other critics, it was in fact a work that mainly

owed its excellence to the creative screenwriting of Herman J.

Mankiewicz, who was virtually the sole author of the script. This

mainstream revisionist view was subsequently complemented by

Robert L.Carringer’s academic book The Making of “Citizen

Kane” (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985). Although

Carringer thoroughly demolished Kael’s claims about Mankiewicz’s

exclusive authorship of the script, he also argued more generally

that Kane’s greatness and singularity stemmed from its status as a

collaborative venture, in which the roles played by cinematographer

Gregg Toland, screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, editorial

supervisor John Houseman, and art director Perry Ferguson were

pivotal. Left to his own devices, Carringer concluded, Welles was

doomed to failure, and this accounted for Kane’s pre-eminence over

Welles’s other films.

This is still a popular position, and there are plenty of arguments in

favor of it — although most of them are rationalizations of Hollywood’s

industrial methods of turning out pictures. There’s a lot at stake

ideologically in classifying Kane as a Hollywood picture, as Kael and

Carringer both do, because the moment one does, one arrives at a

Platonic ideal of Hollywood practice that can be used — and generally

has been used — as a way of dismissing the remainder of Welles’s

career as a filmmaker. Similarly, there’s just as much at stake

ideologically in classifying Kane, as I do, as an independent feature

that uses Hollywood resources — which is not to deny the importance

of collaborators (including actors as well as other participants) on

Kane and other Welles movies, but rather to insist on the bottom

line of who gets the final word on any production. Since everyone

is in agreement that Welles had the final word on what went into

Citizen Kane and that he had the full resources of a Hollywood

studio on that picture, there is a certain amount of scholarly

agreement between Carringer and myself about what the

achievement of Kane consisted of. (There is no such scholarly

agreement between both of us and Kael regarding the film’s

authorship; although her facts have been conclusively disproven

by Carringer and others, Kael has opted to reprint “Raising Kane”

without alteration, apology, or even acknowledgment of any

counterpositions in the significantly titled For Keeps, her latest

[and last] collection.) Where we start to differ is what we take that

achievement to mean. And once we combine the separate-but-

overlapping arguments of Kael and Carringer — which in Kael’s case

also entails viewing Kane as the apotheosis of the Hollywood

newspaper comedy — we wind up with a mainstream domestication of

Welles’s first feature. For roughly three decades after it was made, Kane

remained a troubling anomaly in American film history, an unclassifiable

object that was neither fish nor fowl. But once the domesticating

arguments of Kael and Carringer took hold — the former in the

mainstream, the latter in academia — the movie became regarded as

something much safer and more familiar, a Hollywood classic to stand

alongside The Wizard of Oz, Casablanca, Bringing Up Baby, and

It’s a Wonderful Life. (It’s worth recalling that all four of the latter

movies were far from being “instant” classics either: The Wizard of Oz

“tested” so poorly that M-G-M very nearly deleted “Over the Rainbow”

for making audiences too fidgety; Casablanca initially registered as

little more than a feel-good wartime entertainment; and both Bringing

Up Baby and It’s a Wonderful Life, like Kane, were outright flops at

the box office — assuming their current reputations many years later,

after they were revived repeatedly on TV.)

Revisionist film historian Douglas Gomery, who specializes in

economics, fundamentally agrees with my contention that Welles

was an independent filmmaker throughout his career — and I

hasten to add that he arrived at this conclusion on his own,

without any prompting from me.(2) He argues that the simple

notion that Welles was exploited by Hollywood for the

purposes of Hollywood has it backward: more generally, it was

Welles who exploited Hollywood for his own purposes.

According to Gomery’s analysis, Hollywood of the thirties and

forties was dominated by four relatively strong major studios

(Paramount, Fox, Metro, and Warners), four major studios that

were relatively weak (RKO, Columbia, Universal, and United

Artists), and a number of more marginal studios, the strongest

of which was Republic Pictures. Welles wound up making films

for the first three of the four weaker major studios, for Republic,

and for Sam Spiegel on The Stranger (released by RKO); he

never worked for any of the Big Four. In most cases, Gomery

points out, Welles went over budget and his films wound up

losing money for the studios, all of which contradicts the

notion of him being exploited by Hollywood in general or by

the studios in particular.

_________________________________________________________________________________

[2] “Orson Welles and the Hollywood Industry,” Persistence of Vision no. 7, 1989, pp. 39–43.

So far, so good. Where I begin to part company with Gomery, as

well as with Carringer,3 is in their uncritical acceptance of the business

acumen of those studios when they decided to tamper with Welles’s

work. Everyone is in agreement that Citizen Kane, which wasn’t

tampered with at RKO, lost a certain amount of money, and that

The Magnificent Ambersons, which lost even more money, was

substantially tampered with by the same studio. Although neither

Gomery nor Carringer conclude from this that RKO would have

been commercially justified in tampering with Kane — assuming

that RKO’s contact with Welles had allowed this — they both

irrationally conclude that RKO was commercially justified in

tampering with Ambersons, despite the fact that the resulting

hybrid still lost the studio an enormous amount of money.

Obviously I can’t prove that Welles’s own version would have made

more money, but I seriously doubt that they could prove the contrary.

The only evidence they can summon up to support their view is the

audience responses at the film’s three test-marketing previews, and, as

I hope this book has already demonstrated, this is tantamount to

placing one’s medical faith in a team of witch doctors. Both Gomery and

Carringer accept without qualm the conclusion of studio executive

George Schaefer that the first preview of Ambersons, when a version

approximating Welles’s own version was shown, was a “disaster.”

Certainly we have many eyewitness accounts that a significant portion

of that audience was unsympathetic and even hostile — just as I’m sure

we have evidence that members of the early preview audiences of The

Wizard of Oz started to squirm as soon as “Over the Rainbow” came

on — but I’m not convinced that this constitutes any sort of conclusive

evidence. I’ve seen most of the one hundred and twenty-five “comment

cards” myself — fifty-three of which were positive, some of them

outright raves (“a masterpiece with perfect photography, settings and

acting,” “the best picture I have ever seen”) — and would conclude that

declaring the preview a “disaster” on the basis of those cards is a highly

subjective matter, very much dependent on what one is predisposed to

look for. It all depends on whether the hostile responses definitively

outweigh the favorable responses, and considering that the preview in

question — held at the Fox Theater in Pomona, California on March 17,

1942 — immediately followed a regular commercial screening of a

Dorothy Lamour wartime musical, The Fleet’s In, one might easily

conclude that an audience paying to see something like that might not

have been exactly primed for an unusually long and depressing feature

such as Welles’s version of Ambersons.

Theoretically a preview of Ambersons that followed a commercial

screening of How Green Was My Valley, released the previous year —

even though this might have made for an unusually long program —

might have yielded seventy-two positive responses and fifty-three

negative ones, a difference of only nineteen votes from what actually

transpired. Are Gomery and Carringer absolutely convinced that a

minimum of nineteen viewers at that preview couldn’t have responded

differently if the studio had bothered to schedule the Ambersons

preview after something more appropriate? Or are they merely content

to leave the benefit of every doubt to RKO in this matter?

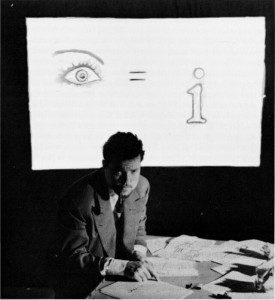

2. Welles as an intellectual. Starting around 1938, when at age

twenty-three Welles became a household name in the United States

through the scandal of his War of the Worlds radio broadcast, the

terms “genius” and “boy genius” became attached to his name with

increasing frequency, and they clung to his public profile to varying

degrees for the remainder of his life and career. On the surface, these

are terms of praise, but as Robert Sklar has demonstrated at length in

a brilliant essay (4), they are just as clearly terms of abuse — especially

within the anti-intellectual context of American popular culture, where

Welles came into prominence in the thirties and forties. Moreover, the

undertow of resentment behind these terms is not merely a matter

of after-the-fact interpretation. It becomes immediately apparent if

one reads the three-part profile of Welles published in the Saturday

Evening Post in early 1940, if one listens to his radio appearances

on popular comedy shows throughout the forties, or if one watches

“Lucy Meets Orson Welles,” an episode of I Love Lucy broadcast in

1956. Even the title and subtitles of the Saturday Evening Post

profile coauthored by Alva Johnson and Fred Smith spell out part of

this undercurrent of hostility: “How to Raise a Child: The Education

of Orson Welles, Who Didn’t Need It” (January 20), “How to Raise a

Child: The Continuing Education of Orson Welles, Who Didn’t Need

It” (January 27), and “How to Raise a Child: The Disturbing Life —

To Date — of Orson Welles” (February 3).

____________________________________________________

4] “Welles Before Kane: The Discourse on a ‘Boy Genius,’ ” Persistence of Vision no. 7, 1989, pp. 63–72.

Interestingly enough, Welles spoke favorably about these articles to

Peter Bogdanovich in 1969 (5), calling them accurate and implying that

they were sympathetic. (More precisely, he noted that the authors had

worked with him closely in preparing the profile, which raises the

possibility that Welles’s own pronounced impulses toward self-criticism

and self-accusation were accurately reflected in the articles.) By the

same token, judging from the many appearances of Welles on comedy

shows of the forties and fifties that I’ve heard and/or seen, he appears

to be completely complicitous and comfortable with the extremely

precocious, imperious, egomaniacal, and intimidating versions of

himself comically presented and ridiculed on those programs. On

July 19, 1946, he even presented an extended parody of his persona—

“Adam Barneycastle,” played by Fletcher Markle — on the Mercury

Summer Theatre, explaining in his introduction that after hearing

Markle’s half-hour Life with Adam on Canadian radio, he couldn’t

resist importing it onto his own CBS radio show.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

[5] This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum, second edition, New York: Da Capo Press, p. 358.

What are we to make of this apparent masochism on Welles’s part,

which seems to go well beyond “being a good sport” about the

threatening figure he seemed to pose to the mass media? The negative

aspects of this image hounded him for the remainder of his career, and

continue to crop up even posthumously in works ranging from the

Oscar-nominated documentary The Battle Over “Citizen Kane”

(1995) and Tim Robbins’s Cradle Will Rock to Welles biographies

by Charles Higham, Simon Callow, and David Thomson. Like most

caricatures, this lampoon of Welles’s personality had some basis in fact,

even if it has tended to obscure other aspects of his character, often to

ruinous effect. It points to fear as well as respect, intimidation as well

as admiration, which was obviously part of the packaging he had to

accept if he wanted to cut a figure in the mass media; and it must be

admitted that Welles seemed to go along with this partial

misrepresention as a show-biz necessity.Unfortunately, this same

distortion would interfere increasingly with public understanding of

what he was up to as an artist, ultimately encouraging the same sort

of mythology that mystifies most accounts of his more serious work

today.

Welles’s reputation as a “genius,” which he eventually began to criticize

in his late interviews, is not the same as his reputation as an intellectual,

but the two images often overlap in the public imagination, especially in

his case. Both are tied to his privileged upper-class background, though

the usual unconscious taboos against discussions of class differences in

American culture muddy the waters even further. This often leads to

outright errors regarding Welles, such as David Thomson’s assertion that

he “always liked his revolutionaries to be sophisticated and well-heeled”

— a premise that rules out, for starters, Jacaré [see above photo], the

central, heroic, real-life radical in the central episode of Welles’s

unfinished docudrama feature about Latin America, It’s All True.

But since Thomson elsewhere characterizes the footage from this

episode, dealing with Jacaré and other poor Brazilian fishermen, as

“picturesque but inconsequential material,” one is forced to conclude

that maybe it’s Thomson and not Welles who likes — indeed, requires

—revolutionaries to be “sophisticated and well-heeled,” at least if they

want to be considered consequential. (6)

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

[6] David Thomson, Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996, pp. 77 and 237.

The relation of culture to money is so fixed in the American popular

imagination that it often becomes difficult to disentangle the two

— a situation much less prevalent in Europe, where, as Jim Jarmusch

once pointed out to me in an interview, street cleaners in Rome

are apt to discuss Dante, Ariosto, and twentieth-century Italian poets,

and “even guys who work in the street collecting garbage in Paris love

nineteenth-century painting.” Welles’s intellectual activity often winds

up imposing a lot of false assumptions about his politics, taking him to

be an elitist rather than a populist — although in fact the reception of

his work ran the gamut from popular (his theater and radio work in the

thirties, his TV appearances) to elitist (most of his films from the forties

onward, despite their populist intentions).

Welles has an interesting exchange on this issue with Bogdanovich

in This Is Orson Welles:

PETER BOGDANOVICH: You once said that your tastes don’t shock the

middle-class American, they only shock the American intellectual. Do

you think that’s true?

ORSON WELLES: Yes.

PB: Why?

OW: Because I’m a complete maverick in the intellectual establishment.

And they only like me more now because there’s even less communication

between me and them. I’ve become kind of exotic, so they start to accept

me. But basically I’ve always been completely at odds with the true

intellectual establishment. I despise it, and they suspect and despise me. I

am an intellectual, but I don’t belong to that particular establishment.

PB: Well, it’s true that America likes its artists and its entertainers to

be either artists or entertainers, and they can’t accept the combination of

the two.

OW: Or any combination. They want one clear character. And they

don’t want you to be two things. That irritates and bewilders them. (7)

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

[7] This Is Orson Welles, op. cit., pp. 243–244.

This final formulation expresses the problem in a nutshell. Welles

was too much of a vulgar entertainer to endear himself to the

intellectual establishment. But he was too much of an artist and

intellectual to endear himself to the general public unless he mocked

and derided his artistic temperament and intellectualism, thereby

proving he wasn’t on a higher level than his own audience and

ratifying his own populism. (Significantly, to the best of my knowledge,

this wasn’t a form of self-disparagement he ever practiced in Europe,

where it wasn’t deemed necessary to establish his equity with the

public.) To a large degree, straddling this contradiction is what his art

and his life were all about.

(to be continued)