Commissioned by BFI Publishing and published in the November 2014 Sight and Sound. This version is slightly tweaked. — J.R.

In an amusing, satisfying, and highly persuasive rant in Time Out in 1977, J.G. Ballard took on the cultural phenomenon of Star Wars (1977), including some of its historical and ideological consequences. Noting that “two hours of Star Wars must be one of the most efficient means of weaning your preteen child from any fear of, or sensitivity towards, the death of others”, he also reflected on the overall impact of George Lucas’s blockbuster on science-fiction movies:

“The most popular form of s-f — space fiction –- has been the least successful of all cinematically, until 2001 and Star Wars, for the obvious reason that the special effects available were hopelessly inadequate. Surprisingly, s-f is one of the most literary forms of all fiction, and the best s-f films — Them!, Dr. Cyclops, The Incredible Shrinking Man, Alphaville, Last Year at Marienbad (not a capricious choice, its themes are time, space and identity, s-f’s triple pillars), Dr. Strangelove, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Barbarella, and Solaris — and the brave failures, such as The Thing, Seconds, and The Man Who Fell to Earth, have all made use of comparatively modest special effects and relied on strongly imaginative ideas, and on ingenuity, wit, and fantasy.

“With Star Wars the pendulum seems to be swinging the other way, towards huge but empty spectacles where the special effects — like the brilliantly designed space vehicles and their interiors in both Star Wars and 2001 — preside over unoriginal ideas and derivative plots, as in some massively financed stage musical where the sets and costumes are lavish but there are no tunes. I can’t help feeling that in both these films the spectacular sets are the real subject matter, and that original and imaginative ideas — until now, science fiction’s chief claim to fame — are regarded by their makers as secondary, unimportant and even, possibly, distracting.”

One could of course quarrel with some of Ballard’s particular choices and categories — such as why Seconds qualifies as a “brave failure” alongside Barbarella‘s presumed success, and whether Last Year at Marienbad, for all its imaginative displacements, really qualifies as science fiction at all. And Ballard’s larger point about placing images and ideas in separate categories neglects the degree to which they interact and are mutually interdependent. This argument also seems to rule out the provocative ideas in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) as well as the striking images in George Lucas’s THX 1138 (1970), a film he fails to mention. But his larger point about sci-fi films commonly opting for either splashy and expensive effects or more conceptual forms of ingenuity seems to hold, even after one factors in the few cases such as 2001 and Blade Runner where the two seem equally present.

By stressing the capacity of Star Wars to foster either indifference or some form of exhilaration in relation to mass murder (a trait that arguably made the supposedly bloodless Gulf Wars and drones of future decades — not to mention a good many genocidal video games — much easier to promote and ‘sell’ in the public marketplace), Ballard wasn’t implying the absence of any ideological baggage in the relatively ’empty’ and derivative space operas. It hardly seems irrelevant that Lucas freely and consciously modeled some of his shots after prototypes from Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi recruitment epic, Triumph of the Will (1935), as well as from Flash Gordon serials and WWII aerial combat footage. Yet it seems no less significant that a major polemical and ideological point in many less ostentatious, idea-driven speculations is that the future has already arrived, and that the present and future are both locked into the same dystopian nightmare. This is true of The Damned (Joseph Losey, 1961: see photo at the head of this article), The Most Dangerous Man Alive (Allan Dwan, 1961), La Jetée (Chis Marker, 1962), Dr. Strangelove (Stanley Kubrick, 1964), Alphaville (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965), The War Game (Peter Watkins, 1965), It Happened Here (Kevin Brownlow, 1966), Fahrenheit 451 (François Truffaut, 1966), Seconds (John Frankenheimer, 1966), Privilege (Watkins, 1967), Je t’aime, je t’aime (Alain Resnais, 1968), The Gladiators (Watkins, 1969), Mr. Freedom (William Klein, 1969), Ice (Robert Kramer, 1970), Punishment Park (Watkins, 1971), Glen and Randa (Jim McBride, 1971), A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971), THX 1138 (Lucas, 1971), Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979), and Stalker (Tarkovsky, 1979). In all these films, to varying degrees, shooting ‘on location’ — or at least on sets that feel contemporary — is commonly made to seem like peering into the future. (If the space station in Solaris represents a more conventional projection into the future, the lengthy highway sequence preceding it is a more precise example of what I mean.)

Properly speaking, Brownlow’s It Happened Here — an intricate imagining of England in 1944 if it had lost the war in 1940 and been occupied by the Germans — qualifies as science fiction and his second feature, Winstanley (1975) — an account of the failed effort of a nonviolent religious sect called the Diggers to establish a commune in Surrey in 1649 — qualifies as history, a period piece. But to my mind both films are a kind of science fiction, insofar as a vanished era becomes the focus of the sort of curiosity and wonder commonly reserved for the future. In part because of the fanaticism about period details, both works are theoretically and stylistically somewhat naïve movies, endowing the past with a voluptuous sense of mystery rarely found in more accomplished pictures. By the same token, however, one could cite a comparable sense of awe and mystery in such accomplished period epics as Watkins’s Culloden (1964) and Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975) –- displaying a passionate curiosity that closely parallels some of their earlier forays into science fiction.

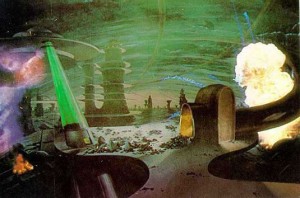

Some of the same reverence towards the historical past that I associate with Brownlow, Kubrick, and Watkins can be found in such equally neglected features as Stanley Kwan’s Centre Stage (aka Actress, 1991) and Richard Linklater’s The Newton Boys (1998). Neither of these can remotely be considered as science fiction, but both induce a sense of wonder in relation to space and the viewer’s imagination. In contrast to the reductive nostalgia of Disneyland and Disney World’s ‘Main Street USA’ — where every brick and shingle is five-eighths the original size so we won’t feel overwhelmed by the world of our ancestors — the depiction of the 1920s in both these films makes them seem, if anything, more spatially vast than the present. And a similar sense of vastness and infinite reaches is conveyed in such relatively big-budget sci-fi films as This Island Earth (Joseph M. Newman, 1955), Forbidden Planet (Fred M. Wilcox, 1956), 2001, and Solaris.

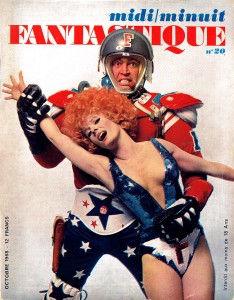

Another special case is Klein’s Mr. Freedom, arguably closer to satire and political allegory than to science fiction per se, although I’ve cited it nonetheless for its use of contemporary locations to suggest the future. More broadly speaking, this feature and the very different Marienbad as well as Cocteau’s Orphée (1950), Alphaville, and Je t’aime, je t’aime, all belong to a special French category known as fantastique, a branch of cinema with less reliance on science and closer ties to comic strips and surrealism. One magazine, the attractive, large-format Midi-Minuit Fantastique, which once featured Mr. Freedom on its cover, was devoted expressly to this subgenre, and lasted for almost a decade, from 1962 to 1971.

As the 20 titles listed above suggest, the 60s and 70s were clearly the golden age of dystopian science-fiction films. Many of them stemmed directly from Cold War anxiety about the Bomb and radiation, but others ranging from Marienbad, Seconds, and 2001 to Solaris and John Boorman’s Zardoz (1974) were more grounded in metaphysical uncertainties. (Back in the 50s, Don Siegel’s 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Jack Arnold’s 1957 The Incredible Shrinking Man managed to combine their metaphysical aspects with Cold War fears, much as Alphaville would do later.) What virtually all these films had in common, in striking contradistinction to the relative gleefulness of Star Wars, was their pessimistic view of the future.

The degree to which this vision was intentional or an inadvertent product of circumstance clearly varied a lot. One might argue, for instance, that Godard, mapping out Alphaville in terms of genre, had neither the budget nor the particular skills needed to create future cityscapes in alternative solar systems, so existing Paris locations had to stand in for these — even though he would consciously capitalize on this limitation by inserting satirical parallels, so that, for instance, postwar low-income housing (les habitations à loyers modiques) become the clinics and madhouses of the future (Les Hôpitaux de la longue maladie). Furthermore, the generic and stylistic parallels Godard found between science fiction and German expressionist cinema (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Destiny, Nosferatu, The Last Laugh, Metropolis, Faust, Sunrise), film noir (The Big Sleep, Mr. Arkadin, Kiss Me Deadly), and the surreal cityscapes of Cocteau in Orphée and Orson Welles’s version of Kafka (The Trial), turned Alphaville into a kind of film criticism composed in the language of the medium and built around these multiple references. Godard once admitted to me in an interview that he only became fully aware of this critical activity years later – before he made chapter 3b of his Histoire(s) du cinéma, where he fully acknowledges the relationship between Alphaville and the play between brightness and darkness in both German expressionist cinema and film noir by superimposing funereal images of candles and deathly gloom from Fritz Lang’s Destiny (1921) over stretches of his own film.

In his 2005 book about Alphaville, Chris Darke expands on this notion by pointing out — and presenting substantial supportive evidence — that both of the principal alleged ‘genres’ that Godard is cross-referencing throughout the film, German expressionist cinema and film noir, are basically inventions of French criticism in the 1950s. Lotte H. Eisner first formulated the former in L’Ecran démoniaque: Influence de Max Reinhardt et de I’expressionisme in 1952 (revised and expanded in 1965, and translated into English as The Haunted Screen in 1969), and Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton the latter in Panorama du film noir américain in 1955. And indeed, part of the conceptual brilliance of Alphaville can be seen in the various ways that Godard folds in other historical and geographical markers that exhibit related traits and tendencies: memories of the French Occupation in Orphée, the postwar and post-Holocaust view of Kafka offered by Welles in The Trial, the Franco-American ambience of Lemmy Caution thrillers, the Franco- Soviet alliances suggested by Caution’s alleged employer (Figaro-Pravda), and so on.

Later on, George Lucas, a less political and less critical-minded cinematic magpie, used many locations from northern California in THX 1138 to suggest the future via the present, along with pronounced visual echoes of Godard (white on white) and Michelangelo Antonioni (off-center framing) in his own ‘Scope compositions. (Strictly speaking, Antonioni didn’t make science-fiction films, but there are nonetheless suggestions of dystopia threaded through much of his work — especially in the stretch from L’Eclisse in 1962 to Zabriskie Point in 1970, including Red Desert, his 1965 short Il provino, and Blow-Up).

More systematically, all four of Watkins’s dystopian films cited above are founded on the principle of using pseudo-documentary techniques to project the present into the future with a minimum of fuss and a maximum of believability — extensions of the same basic principles that yielded Welles’s celebrated radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds in 1938 and the parody of a March of Time newsreel in the opening stretches of Citizen Kane three years later, not to mention scores of subsequent ‘mockumentaries’ such as This Is Spinal Tap (1984). One could indeed argue that, apart from Alphaville, The War Game was probably the most influential single low-budget sci-fi film of the 6os, although thanks to the film’s initial suppression and the outsider status of Watkins in relation to the British film industry it would take many years for its impact to register and be fully absorbed within the mainstream.

Science fiction without fancy production values doesn’t necessarily entail small budgets. Consider such pricier black-and-white productions as the relatively square On the Beach (Stanley Kramer, 1959) and the relatively hip The Manchurian Candidate (John Frankenheimer, 1962), where the budgets went mainly for the stars (Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, Fred Astaire and Anthony Perkins in the former; Frank Sinatra, Laurence Harvey and Janet Leigh in the latter) rather than any special effects. It could be argued, however, that one tour de force sequence in the latter film, equal to some of the disorienting displacements in Marienbad — in which a ladies’ garden club mutates into a Chinese communist demonstration of brainwashing within the space of the same panning 36o-degree camera movement – qualifies as a special effect in its own right.

One salient factor in science-fiction films overlooked by Ballard is the degree to which clever, strategic employments of the viewer’s imagination can sometimes count for as much as expensive special effects — and can indeed maximize the impact of those special effects when they finally arrive. It’s worth recalling that the giant ants in Them! (Gordon Douglas, 1954) don’t make their initial on-screen appearance until a full half-hour into the story a third of the way through, and the use of sound effects prior to their entrance is as effective as in any of Val Lewton’s low-budget chillers a decade earlier. For that matter, the invading monsters in The Thing from Another World (Christian Nyby, 1951) and The War of the Worlds (Byron Haskin, 1953) took even longer to make their full on-screen entrances. And even Star Wars works on the assumption that the enchantment of any creature, landscape, gadget or set decreases in ratio to the length of time it’s on the screen -– a withholding premise already evident in both the Krel episodes of Forbidden Planet and the brief, last-minute glimpses of a perishing otherworldly city in This Island Earth. Nothing incidental or scenic (such as the twin moons of Tatooine, or the binoculars Luke uses while scouting for R2-D2) is allowed to slow down the rapidly paced narrative, but is generally packed along en route. (A rare exception is made for diverse beasties in the Mos Eisley western saloon sequence, where spectacle for once triumphs over event, significantly occasioning the greatest amount of scorn and ridicule from Ballard: “The parade of extraterrestrials…comes on hilariously like The Muppet Show, with shaggy monsters growling and rolling their eyeballs. I almost expected Kermit and Miss Piggy to swoop in and introduce Bruce Forsyth.”) All of which suggests that the notion of economy in science-fiction cinema isn’t simply a matter of budgets and profits, but also a matter of many other kinds of investments and expenditures, on the part of viewers as well as filmmakers.