This was written in May 2014 for an Italian volume about fantastique cinema between 1980 and 2010 coedited by Antonio Gragnaniello. — J.R.

Speaking to Tom Milne and Richard Combs in Monthly Film Bulletin, the director of Aspern, Eduardo de Gregorio (1942-2012), avowed that “it was never meant to be a fantastique film”— which isn’t surprising given that its source, Henry James’ novella The Aspern Papers, has no relation to that genre either. But it was regarded by several French critics as having some relation to fantastique, apparently for two reasons: because fantastique as opposed to fantasy is often regarded as a matter of style and/or atmosphere rather than content, and because the better known works of de Gregorio — such as his scripts for Jacques Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau, Duelle, and Noroît and his own Sérail and Tangos volés—clearly belong to fantastique, while his work as a whole has clear links to both the 19th century Gothic tradition and the so-called “magical realism” of 20th century Latin American literature.

Even though much of Henry James’ dialogue is carried over into Aspern (translated into French), its basic plot — an obsessive literary scholar (the narrator in James’ tale) insinuates himself into the Venice household of an aged woman cared for by her lonely spinster niece with the aim of procuring her love letters from Aspern, a long-deceased romantic poet she was once involved with — undergoes several decisive changes in de Gregorio’s version, scripted by his partner at the time, Michael Graham. The story is set in contemporary Lisbon rather than Venice in the 1880s — a necessity given the project’s Portuguese funding — and the literary profiles of both the hero (played awkwardly and not always convincingly by Jean Sorel) and the absent Aspern are broadened to make both of them novelists. (The main item sought by the hero is now a “lost” novel, although Aspern is still known in part for his poetry.) Even more crucially, albeit far more subtly, the hero’s implicit courting of the niece in order to further his aims is modified both by the casting of Bulle Ogier as the niece and the fact that the hero now has a secret girlfriend (Ana Marta) who travels with him to Lisbon (but who never comes to the villa). James, a master of indirection, concludes his first chapter with the hero joking to a friend and confident, before arriving at the villa, that he will have to “make love to the niece,” and the friend replying, “Ah, wait till you see her!” — which clearly (if tactfully) implies that the niece is unattractive. So even though the niece remains the central and most important character in both the novella and the film, she is a far more glamorous and potentially romantic figure in Aspern.

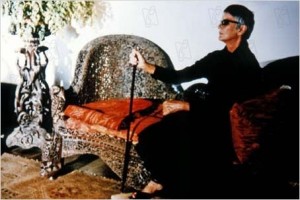

Shot by Acacio de Almeida and costarring Alida Valli as the grande dame, Aspern, which is probably de Gregorio’s weakest feature, might have come closer to fantastique if producer Paulo Branco had allowed de Gregorio to show Aspern and his former lover in a series of planned flashbacks. The only remnant of this plan in the film is a conversation between the hero and his girlfriend in their Lisbon flat when we see shadows of the past lovers briefly reflected on the wall, rather like the shadows glimpsed in a stable by the hero of Dreyer’s Vampyr (one of de Gregorio’s favorite films). Combined with the more atmospheric scenes set in the villa’s garden, this suggests more of the Gothic trappings that de Gregorio usually fancied.

Jonathan Rosenbaum