Both of these reviews appeared in the July 1975 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin (vol. 42, no. 498). –- J.R.

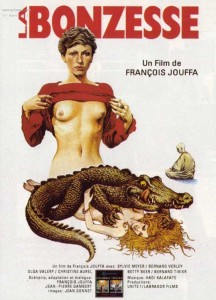

Bonzesse, La

France, 1974

Director: François Jouffa

Bored with her life, Béatrice goes to work in Mme. Renée’s upper-class Parisian brothel, where she is given the name of Julie and quickly initiated into the tricks of the trade. Flashbacks suggest that she was sexually abused by her stepmother, and grew up believing that the life bf a courtesan was glamorous. On her second day at work, she is attracted to a client, Jean-François, a wealthy advertising man who chooses not to have sex with her but asks her for a date that evening. She accepts and winds up living at his flat, but he repeatedly avoids having sex with her. In desperation, she resumes work at the brothel in the daytime without telling him, then leaves him one night to go home with her friend Martine and her boyfriend. As she gradually saves up enough money to fly to Ceylon — where she hopes to attain spiritual peace — she becomes increasingly depressed by the grotesque needs of the clients who come to the brothel, the jealousy of a fellow worker, and the overall sordidness and sadness of the place. In Ceylon, she studies meditation, has her head shaved and becomes a bonzesse (Buddhist priestess); back in Paris, Martine assumes Béatrice’s former job and working name at the brothel and makes love with Jean-François, who pretends that ‘Julie’ is Béatrice.

Bored with her life, Béatrice goes to work in Mme. Renée’s upper-class Parisian brothel, where she is given the name of Julie and quickly initiated into the tricks of the trade. Flashbacks suggest that she was sexually abused by her stepmother, and grew up believing that the life bf a courtesan was glamorous. On her second day at work, she is attracted to a client, Jean-François, a wealthy advertising man who chooses not to have sex with her but asks her for a date that evening. She accepts and winds up living at his flat, but he repeatedly avoids having sex with her. In desperation, she resumes work at the brothel in the daytime without telling him, then leaves him one night to go home with her friend Martine and her boyfriend. As she gradually saves up enough money to fly to Ceylon — where she hopes to attain spiritual peace — she becomes increasingly depressed by the grotesque needs of the clients who come to the brothel, the jealousy of a fellow worker, and the overall sordidness and sadness of the place. In Ceylon, she studies meditation, has her head shaved and becomes a bonzesse (Buddhist priestess); back in Paris, Martine assumes Béatrice’s former job and working name at the brothel and makes love with Jean-François, who pretends that ‘Julie’ is Béatrice.

Lost somewhere in the middle of La Bonzesse –– subtitled Les Confessions d’une Enfant du Siècle — is the implicit notion that the filmmakers are after something more edifying and moralistic than a routine exercise in titillation. Armed with cultural baggage ranging from Colette to Kate Millett, Béatrice embarks on her prostitute’s career as a sort of adventuresome existential sport, choosing the trade name of Justine until Mme. Renée harshly reminds her that the work of a whore is serious business. A sober title at the beginning informs us that the film is inspired by “real” testimonies of prostitutes, and a certain effort seems to have been made to depict some of a brothel’s more everyday activities (although the 150-franc-charge per girl, specialties included, seems a bit far-fetched for a classy Parisian establishment, even at pre-inflationary prices). Alas, too much of the film depends on the capacity of the actors to register as interesting and sympathetic individuals, legible and likable, white script and editing alike tend to strand them in isolated air pockets of meandering plot and fuzzy motivations with nowhere in particular to go. One is never quite sure whether to ascribe Jean-François’ sexual abstinence to outright impotence or to a form of emotional reticence roughly paralleling that of Bemard Verley’s character in. Rohmer’s L’Amour l’après-midi; a bored afternoon spent by Béatrice in his flat is made doubly tedious by slack direction; the abrupt cutting to and from the brothel in the final reel seriously impedes narrative continuity. And the specifics delineating Béatrice’s spiritual quest (“Sex is one of the ways to God”) wind up becoming even more grotesque than some of her kinkier clients: François Jouffa’s pièce de résistance concluding the film is to cut back and forth between a bald Béatrice chanting Buddhist prayers in Ceylon and an orgasmic Martine moaning while she has sex with Jean-François in Paris, with the latter sounds ultimately overlapping those which accompany the former images. Too ‘sincere’ to be strictly risible yet too outlandishly contrived to be even halfway believable, this fatal montage banishes La Bonzesse to a doomed and innocent netherworld paved with good intentions.

Lost somewhere in the middle of La Bonzesse –– subtitled Les Confessions d’une Enfant du Siècle — is the implicit notion that the filmmakers are after something more edifying and moralistic than a routine exercise in titillation. Armed with cultural baggage ranging from Colette to Kate Millett, Béatrice embarks on her prostitute’s career as a sort of adventuresome existential sport, choosing the trade name of Justine until Mme. Renée harshly reminds her that the work of a whore is serious business. A sober title at the beginning informs us that the film is inspired by “real” testimonies of prostitutes, and a certain effort seems to have been made to depict some of a brothel’s more everyday activities (although the 150-franc-charge per girl, specialties included, seems a bit far-fetched for a classy Parisian establishment, even at pre-inflationary prices). Alas, too much of the film depends on the capacity of the actors to register as interesting and sympathetic individuals, legible and likable, white script and editing alike tend to strand them in isolated air pockets of meandering plot and fuzzy motivations with nowhere in particular to go. One is never quite sure whether to ascribe Jean-François’ sexual abstinence to outright impotence or to a form of emotional reticence roughly paralleling that of Bemard Verley’s character in. Rohmer’s L’Amour l’après-midi; a bored afternoon spent by Béatrice in his flat is made doubly tedious by slack direction; the abrupt cutting to and from the brothel in the final reel seriously impedes narrative continuity. And the specifics delineating Béatrice’s spiritual quest (“Sex is one of the ways to God”) wind up becoming even more grotesque than some of her kinkier clients: François Jouffa’s pièce de résistance concluding the film is to cut back and forth between a bald Béatrice chanting Buddhist prayers in Ceylon and an orgasmic Martine moaning while she has sex with Jean-François in Paris, with the latter sounds ultimately overlapping those which accompany the former images. Too ‘sincere’ to be strictly risible yet too outlandishly contrived to be even halfway believable, this fatal montage banishes La Bonzesse to a doomed and innocent netherworld paved with good intentions.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

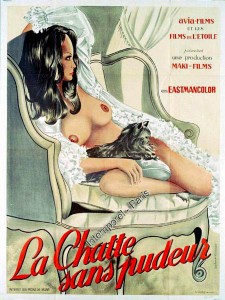

Chatte sans pudeur, La (Sexy Lovers)

Chatte sans pudeur, La (Sexy Lovers)

France,1974

Director: Jack Angel

Hitchhiking on their vacation with no set destination, Martina and Julie are picked up by a man with lecherous designs on the former; that night, whiie Julie is asleep in the back seat, he drives off the road, forces Martina out of the car, and tries to rape her until Julie wakes up and brains him with a big stick. The girls flee to a house whose inhabitants are away; Julie is afraid she killed the man, but Martina convinces her not to phone the police, and unsuccessfully tries to seduce her. In the morning, Patrick Stevens, the son of the woman who owns the house, returns from Paris, where he has just broken off his engagement to his fiancée; after being initially shocked at finding the girls, he agrees to let them stay once they’ve described their plight. Drinking and- dancing with both girls that night, he declares his affection for Julie, but once he retires to his room Martina follows and seduces him, reducing Julie to tears. The next day, his mother Paula and stepfather George arrive; the latter proves to be the rapist, but Martina deliberately deliberately conceals the fact and convinces Julie that it’s another man. She then proceeds to blackmail him into drawing money from his wife’s account, and finally agrees to sleep with him after he-pays her. While Paula visits her stockbroker friend Paul, his wife Patricia drags George into a storage room to make love; Martina follows them and insists on having sex with Patricia herself. Back at her house, Paula comes into Martina’s room and finds George there along with the blackmail money. After Martina leaves, Paula drives George to the spot where the attempted rape took place and leaves him there; she announces to Patrick and Julie — now happily and inseparably in love — that she’s quite content to forget her errant husband.

Despite some fairly dotty dubbing that seems to turn Julie intermittently into Jilly, and most of the characters into dummies handled by in uncoordinated ventriloquist, most of Sexy Losers is roughly only half as bad as the above synopsis might suggest. For one thing, the sheer melodramatic Manichaeanism that juxtaposes its evil and angelic couples (Martina and George, Julie and Patrick, respectively) lends a certain variety and contrast to the soft-core sexual interludes, and both of the ladies involved have more personality than is usually allowed for in such enterprises; production values are slicker than the norm, and the handling of the plot is competent enough to generate a modicum of narrative interest. Most surprising of all is the performance — or at least the visual half of it -– from the actress playing Paula, the abused and deceived middle-aged widow; the sequence in which she discovers her gigolo-husband’s theft and true identity, and then sets about removing her jewels and make-up in front of a mirror, is ample proof that genuine distinction can occasionally be found in the most improbable of circumstances.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM