The following was written for CITIZEN PETER, a very handsomely produced and multilingual 476-page book celebrating the late Peter von Bagh’s 70th birthday, in late August 2013, coedited by Antti Alanen and Olaf Möller. — J.R.

Preface

Peter von Bagh is the man who convinced me to purchase my first multiregional VCR in the early 1980s. So he has a lot to answer for — including, just for starters, my DVD column in Cinema Scope.

We’ve met at various times in Paris, London, New York, Southern California, Chicago, Helsinki, Sodankylä, and Bologna — and probably in other places as well, although these are the ones I currently remember. The first times were in Paris in the early 1970s, when he looked me up, and it must have been either in San Diego in 1977 or 1978 or in Santa Barbara between 1983 and 1987 that he convinced me to buy a multiregional VCR. Most likely it was the latter, where I was mainly bored out of my wits apart from my pastime of taping movies from cable TV, and Peter maintained that if we started swapping films through the mail, a multiregional VCR would allow me to play some of the treasures he could send me. The first treasures he sent included Fritz Lang’s Indian films, several films by Carl Dreyer, Jean Renoir’s La Nuit de Carrefour, Josef von Sternberg’s The Saga of Anatahan, Jacques Tati’s Parade, Tay Garnett’s Her Man, and several more that would otherwise have been completely inaccessible to me then even if I’ve been living at the time in New York rather than Santa Barbara. So, to borrow a simile from another friend, Edgardo Cozarinsky, you might say we were like medieval monks copying illuminated manuscripts for one another, trying to keep culture alive during the Dark Ages, in two “remote” outposts.

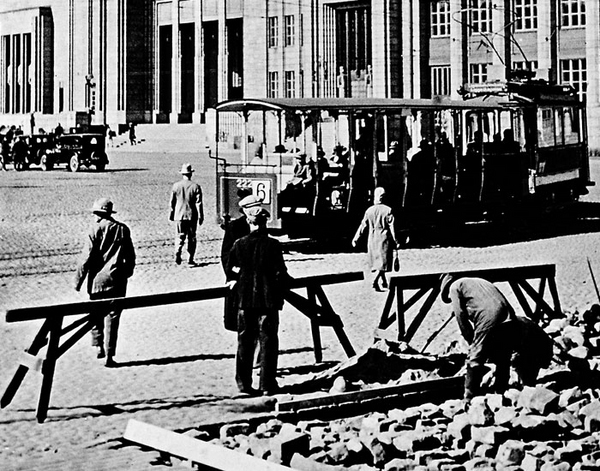

But I’m sure that, even if none of this happened, I still would be mightily impressed by Helsinki, Forever (2008), a DVD of which arrived unexpectedly in the mail in early 2009. A lovely city symphony that is also a history of Helsinki (and incidentally, Finland, Finnish cinema, Finnish literature and art, and Finnish pop music), recounted with film clips, paintings, and still photographs by three voices (two male, one of them von Bagh’s, and one female — each one periodically reciting different segments in the film’s poetic and essayistic discourse). The continuity is more often geographical than chronological, although there’s also a lot of leaping about spatially as well as temporally. At separate stages we’re introduced to the best-ever Finnish camera movement and the best Finnish musical, are invited to browse diverse neighborhoods and eras (and to ponder striking contrasts in populations, auto accidents, and divorce rates), and are finally forced to admit that a surprising amount of very striking film footage has emerged from this country and city.

Almost a year later, I selected Helsinki, Ikuisesti as a Critic’s Choice at the Trumsø International Film Festival, held January 18-24, 2010 near the northernmost reaches of Norway — even further north than Sodankylä, where Peter’s Midnight Sun Film Festival, which I’d attended in the summer of 1998, is held. I was surprised to discover that this was its first screening in Scandinavia, at least outside of Finland, and even though I’m delighted that it’s played at many other venues since then, it’s still a long way from receiving the kind of recognition it clearly deserves and just as clearly will receive over the coming years. And the following remarks will attempt to suggest just a few of the reasons why.

1

I’ve only been to Helsinki twice, both times on very brief stays just before and just after my four-day visit to Sodankylä in 1998, with Peter serving as my main guide to the city on both occasions. One of my more vivid recollections is of mentioning to Peter during the second of these visits how impressed I’d been the previous night, while channel-surfing in my hotel room, to find two films playing simultaneously on Finnish TV, both in pristine prints — Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries and Robert Bresson’s Lancelot du lac. But far from being impressed, and still thinking in some ways like a medieval monk, Peter was miffed that the local TV programmers were so thoughtless that they could screen both films at once, meaning that the local film buffs couldn’t tape both of them.

This may seem like a radical position, but, like Helsinki, Forever, it’s a casual and practical, everyday form of radicalism that seems to come naturally to Peter rather than any sort of studied posture. It even matches his film’s overall attitude and methodology whereby the filmic equals the literary (poetry and fiction), and both are in constant dialogue with the painterly and various forms of music (classical and popular), architecture, and sculpture, as embodiments of Helsinki’s history and essence. Indeed, the only public art that seems absent from Helsinki, Forever is theater (dance, by contrast, is momentarily present in a bit from a 1957 rock movie), and that may partially be because this is mainly a film of exteriors in which even the few interiors — such as a cinema auditorium and a few sumptuous restaurants — tend to be palatial.

Indeed, the continuity here is more often geographical than chronological, although there’s also quite a lot of leaping about spatially as well as temporally. One telling passage delving into the “overlapping historical meanings” of certain images gives us “year 1938, the filming of the movie; year 1918, the year of the original novel; year 1905, where the story is set.” The fact that “where” replaces “when” in the final phrase implies that the persistence of place is what holds Helsinki together more than the diverse fluctuations of time.

There’s a startling sociological observation that crops up at one point in the commentary: “In 1915, there were nineteen divorces in Helsinki. In 1990, the number was 2000.” But the key “place” here is neither 1915 nor 1990 but a poignant, mysterious, and beautiful clip concerning a couple and a shop window from a 1947 film, Edvin Laine’s Kultamitalivaimo; and even though the commentary implies some connection between this clip and a divorce — meanwhile suggesting that the divorce in question may not be permanent — all those viewers like myself who haven’t seen the film are obliged to invent their own narratives, divorce and all, to go with it.

Much of the film, in fact, offhandedly assumes a certain familiarity with Finnish history, cinema, and art that many of us don’t have, and this is part of what’s so wonderful about it — making it an interactive game with the viewer’s imagination whenever one is required to fill in the blanks, and generously treating us as equals rather than as novices to be lectured at.

2

“’Few movies may boast a stronger opening sequence, and few movies offer such an extraordinary finale. And in-between I guess what I admire most is the fluidity of the editing, your way to play with time in a manner that comes at once as always surprising and perfectly natural. Helsinki deserves its rank among the great “city-poems”, and I’d rate it above Ruttmann, for instance, for one reason: if I read in his Berlin the social commitment and the aesthetic maestria, I don’t feel the personal acquaintance with the city, its history, its ghosts, that I found in yours. Also something that many have a tendency to underestimate but which for me is crucial: the music. The Zeppelin sequence by itself carries a haunting beauty, akin to Fellini’s liner, but I don’t think it would attain this climax of emotion if at that moment the music didn’t bring the perfect tune of melancholia. So with the choice of incredible documents and the unfailing mixture of both musical items, editing and score, you made an unforgettable film.” –- Chris Marker in a letter to Peter von Bagh

“Paean to these cities that you inhabit both, the one called Helsinki and the other called Cinema” –- Jean-Pierre Gorin to Peter von Bagh

It makes perfect sense that Chris Marker, a writer who regarded photography and cinema as literature by another means, would warm to Helsinki, Forever, a film that alludes to Kafka and Faulkner, Proust and Dostoevsky as incidental guides to what makes Helsinki so Helsinkian. Most often, Marker added his commentaries to his own footage, but the fact that he usually treated his own footage as if it were found footage, allowing him the full benefit of l’esprit de l’escalier in reinterpreting its meaning and essence, means that he was essentially working the same side of the street as Peter. (“Notice that amidst each great event, you’ll find a child’s eyes,” says Peter’s commentary, in one of his most Markerian, illustrative moments.) This is why Marker, for a certain spell, was one of the regular visitors to the festival in Sodankylä, and, luckily for me, 1998 was part of that spell — so that I’m proud to report that a few seconds in Peter’s Sodankylä Forever (2010) actually capture the two of us chatting, during the only time we ever met.

It also makes sense that Jean-Pierre Gorin sees Helsinki and Cinema as the two places where Peter von Bagh lives. The miracle is how thoroughly he can honor both at the same time, and in the same way, without getting either one to play second fiddle. “We don’t live in the present alone,” he says at the very beginning. “The past with all its memories, events and experiences is alive in us. Often, the past is more powerful than the present.” Because to speak about Helsinki and Cinema ultimately means to speak about everything else.