Commissioned by Richard Porton and written for (and published by) On Festivals: 03 (Dekalog), edited by Richard Porton, New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. Because of the length of this, I’m running it in two parts. — J.R.

I’m pretty sure the first film festival I ever attended was the third New York Film Festival, at age 22 in fall 1965, to see Alphaville. In 1963, I probably would have attended the first New York Film Festival if I hadn’t transferred from Washington Square College to Bard College, two hours up the Hudson, about half a year earlier. Later that same year, I took over the Friday night film series at Bard, but every once in a while I’d forego one of my own selections in order to take a weekend trip to New York and see something new I was especially curious about; my first looks at Muriel and Dr. Strangelove were during two such excursions. And my curiosity about what Jean-Luc Godard would do with science fiction was enough to persuade me to hop on the train or catch a ride with a classmate. As it turned out, I found the film silly, not really understanding most of its allusions to contemporary Paris or German expressionist cinema. Taking the movie as ‘straight’ SF, or at least trying to, made me only slightly more appreciative than John Simon would have been, and I emerged from the screening thinking it was something akin to warmed-over Huxley or Orwell.

On the other hand, this was my first visit to the recently built Lincoln Center, and the way that Alice Tully Hall’s lobbies and stairways reflected some of the movie’s creepier and glossier architecture momentarily left a more favorable impression. (It wasn’t until a few years later, while watching an English-dubbed version of the film on late-night TV, while stoned on grass with a friend, that I started to appreciate the movie in earnest, sensually as well as intellectually.) In fact, the only film festival I can recall attending in the 1960s was the annual one at Lincoln Center. Over the next couple of years, while suffering through the pedantic rituals of graduate school on Long Island in order to continue my draft-dodging, I even did some festival coverage for the college newspaper in order to get press credentials — reviewing, among other things, Godard’s Masculine Feminine and Made in USA, Rossellini’s The Rise of Louis XIV, Skolimowski’s Le départ, and the multiply-authored Far from Vietnam (a particular cause celèbre which in some ways made the strongest impression — though it’s barely remembered today except as a period curiosity).

As I subsequently discovered in 1968 and 1969, when I didn’t write any festival reviews, getting press accreditation for the New York film festival in those days was a fairly simple and straightforward matter. By this time, I was already edging my way out of graduate school, now that being both 25 and from Alabama (where enlistments in the military were relatively common) enabled me to feel safer from the threat of being drafted. I was also beginning to become more professionally involved with film criticism because an entrepreneurial friend had hired me to edit a collection called Film Masters (a book that led me to postpone some of the work on my second novel for the better part of a year, though like both my novels it never wound up in print.) And being part of the festival’s freebie crowd at press screenings gave me a pleasant sense of belonging that I tended to take for granted back then.

The same thing was true at the Cannes film festival the first time I attended, in May 1970 -– having by then moved to Paris from New York the previous fall. All I had to do to get a press card was use some printed stationary belonging to a nonexistent publisher produced by a New York friend for other purposes -– the same friend who’d hired me to edit Film Masters and then had sold it as a package to McGraw-Hill –- and invent a magazine I’d supposedly be writing my coverage for. The following year, however, the Cannes press office was onto my deception and demanded something more real and verifiable. Fortunately, I’d already started to write for the Village Voice by then, about my brief adventures as an extra on Robert Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer, and wound up doing my coverage for them the next two years in a row, after which I managed to write about the festival for Film Comment and London’s Time Out in 1973. (The only glitch in 1971 was that Amos Vogel got the same assignment from a different Voice editor. Once we discovered that neither of us had an exclusive beat, we sorted out the films between us and wrote separate articles.)

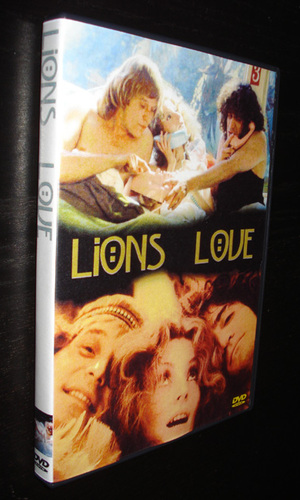

Mythically and practically, my first year at the Cannes festival was what finally edged me into the outer edges of the Paris film world, because I wound up meeting more people there in ten days than I’d met in Paris during half a year. One of the first of these was Carlos Clarens, a Cuban film critic whom I immediately recognized on the Croisette from having seen him play himself in Agnes Varda’s Lions Love -– a mixture of documentary and fiction about Hollywood hippies that I’d seen at the New York Film Festival in 1969. When I introduced myself, I believe he was en route to his second viewing of Woodstock that day, having already attended a press screening that morning.

My own first look at Woodstock, a memorable experience, was in the festival’s Grand Palais, which was then directly across the street from the Hotel Carlton. Michael Wadleigh, the hippie director –- a tall, commanding figure dressed in suede -– dedicated the film to the four students killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State only five days earlier, and to ‘the many deaths to come,’ I recall he added. When the screening was over, he stood by the exit and calmly handed out black arm bands to anyone who wanted one. I wore one myself for a day or two, but Warner Brothers was giving out Woodstock buttons at the same time, and after a while it began to seem that the arm bands and the buttons were virtually interchangeable; after all, this was Cannes. Then, by the end of the week, as if to prove the point, some boutiques in Cannes started selling black arm bands.

* * *

Virtually all film festivals can be placed in two functional categories -– those that mainly exist in order to facilitate seeing movies and those that mainly exist in order to facilitate selling movies -– and New York and Cannes offered me respective paradigmatic examples of each. It doesn’t follow from this, however, that those dedicated more to seeing films are necessarily any more sophisticated in terms of either their press or their audiences. If I had to single out two festivals where the herdlike reactions of both reviewers and the public tend to be the most philistine, New York and Cannes could easily fit the bill. The only time in my life when I’ve ever heard a Robert Breer animated short booed was at a New York film festival press screening, and Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson have made apt sport (in their piece about the 1975 New York film festival) of the kind of hostility routinely provoked there by ‘difficult’ films. (‘`Is it Ms. Duras’s intention to bore the audience, and, if so, does she feel she has succeeded?’’) And the noisy, petulant walkouts I recall in Cannes during screenings of Dead Man and The Neon Bible in the 1990s –- or the standing ovations at Cannes that greeted certain moments in Electra Glide in Blue in 1973 -– are no less emblematic. Sometimes the herdlike behavior of the press at Cannes was merely a matter of what everyone chose to see. I recall being somewhat taken aback in 1973 that I was the only one I knew who decided to attend a low-profile screening –- apparently the first in the West -– of Teinosuke Kinugasa’s recently rediscovered and mind-boggling 1926 A Page of Madness (1926) rather than a Palais screening of John Frankenheimer’s Impossible Object.

I can no longer remember which years in Cannes I first met Todd McCarthy and David Overbey, two important early contacts. But I do recall that this happened in Todd’s case during his junior year abroad at Stanford, when he was based somewhere in England, and that David, a former English professor, by this time had already moved to Paris from California, where he was living with one of his former students, who worked for UNESCO. This was before Todd went to work for Variety (after a similar but briefer stint at Hollywood Reporter) and David became a programmer for what was then called the Toronto Festival of Festivals, both of which occurred in the mid-1970s. These friendships were characteristic of the kinds of links with fellow cinephiles that could be forged at Cannes. (Another key meeting was a casual conversation with Susan Sontag, whom I’d already known since her Partisan Review days in the early 1960s, that sparked the only script conference I’ve ever attended (in Paris, a short time afterwards) -– when she showed some momentary interest in directing a screenplay based on J. G. Ballard’s The Crystal World that I was then writing for a Paris producer, Edith Cottrell.)

I also can recall my amusement at sometimes seeing the entire selection committee of the New York Film Festival at certain Cannes screenings -– a group that typically consisted of Richard Roud, Andrew Sarris, Molly Haskell, Susan Sontag, and/or one or two others -– walk out of the films in question en masse, as if they all had not only identical tastes but also precisely the same burnout points. (Part of the amusement I felt, rightly or wrongly, was at the way some of these people, New Yorkers especially, seemed to cling to one another compulsively at Cannes in mutually protective ways.) There was something mysterious and inscrutable to me back then about some of their tastemaking decisions, and it wasn’t until I became a member of this committee myself in the years 1994–97, thereby allowing me to resume my attendance at Cannes, that I started to understand some of the practical logistics of that group. During the early 1970s, I was usually dismayed to discover that the committee seemed to opt for selecting films that already had US distributors; it was only during the 1990s that I discovered that I was sometimes mistaken about the chronology -– that many of these films on the contrary acquired U.S. distributors because they’d been selected by the New York film festival. Also, though I don’t recall ever sitting together with all the other committee members at any Cannes screenings, I did become more aware of the some of the everyday teamlike duties and processes -– such as the fact that we all stayed at the Splendid, a small but relatively deluxe hotel that was conveniently close to the newer version of the Palais (a few blocks down the Croisette from the old one), and often had breakfast meetings together there at 7:15 a.m. before attending the first press screenings at 7:45. I also became aware that the more difficult part of the selection process was the marathon viewing sessions held in New York in early August. (My hotel room, virtually across the street from Lincoln Center, always had a VCR, and typically — after a twelve-hour stint of watching films, interrupted only by a leisurely lunch — I’d be given a few videos to take back to my room as ‘homework’. After awhile, it became easier for me to perceive how the New York Film Festival could have passed -– or subsequently would pass -– on such major masterpieces as A Brighter Summer Day, The Aesthenic Sydrome, and Inquietude, as well as apparently all the features of such major filmmakers as Pere Portabella and Pedro Costa.Working in such conditions of daily sensory and intellectual overload, the surprising thing was that committee members were able to functioncritically at all.)

One cherished memory I have of Cannes during the 1970s was a movie theatre called Le Français that no longer exists today, where the films of the Quinzaine des Réalisateurs were shown. This was a series that, if I’m not mistaken, was launched in 1969 as a kind of alternative venue to the festival’s main events in the Palais, and in those days this was still a distinction that meant a great deal. Relatively ‘noncommercial’ films at the Palais were few and far between — a rare exception was Jean Eustache’s 210-minute La maman et la putain in 1973 -– so most of the edgier fare that I saw there in that period was at Le Français, including such items as Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Brother Carl, How Tasty Was My Little Frenchmen, Othon, Punishment Park, Valparaiso, Valparaiso!, WR: Mysteries of the Organism, and two particular oddball favorites, Vampir-Cuadacuc and Some Call It Loving. Best of all, there was a bar in this cinema with a large plate-glass window enabling me to glimpse random samples of a film while eating a sandwich and thereby determine whether to return to see the whole thing later.

(to be continued)