A sidebar for Film Comment (July-August 2000). –- J.R.

Viewers feeling flummoxed by Kiarostami’s features might have an easier time with his shorts. The most important are the nine he made between 1970 and 1982 for the film division of the Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, which he co-founded in 1969. Assigned to make educational films, Kiarostami scoured a ‘National Film Board of Canada catalog for ideas, regarding Norman McLaren as one of his guides. More than one of his shorts uses animation: So Can I (1975) juxtaposes the movements of cartoon animals with a live-action boy’s imitations. Kiarostami’s only previous gigs had been making commercials and credit sequences for features, and from what he told me recently, he didn’t consider himself a film artist at the time.

But he took the job seriously, and what emerged are experimental films in the best sense, without pretension, akin in form to what Brecht called “learning-plays”. I don’t mean that they offer political critiques of the state of Iran or the state of Islam, as some American commentators seem to feel all Iranian films should. They’re designed to help kids reflect on ethical, aesthetic, and practical issues ranging from the virtues of brushing one’s teeth (Toothache, 1980) to the specific properties of color and sound. The Colors (1976) recalls some of the abstract montages of Hollis Frampton’s Zorns Lemma via color coding — though it also indulges violent fantasies involving cars, guns, boys, and paint. The Chorus (1982) explores sound and its absence quite differently, in more narrative terms, via an old man who escapes urban noise and his graddaughter by shutting off his hearing aid.

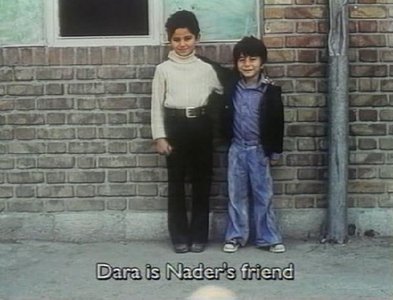

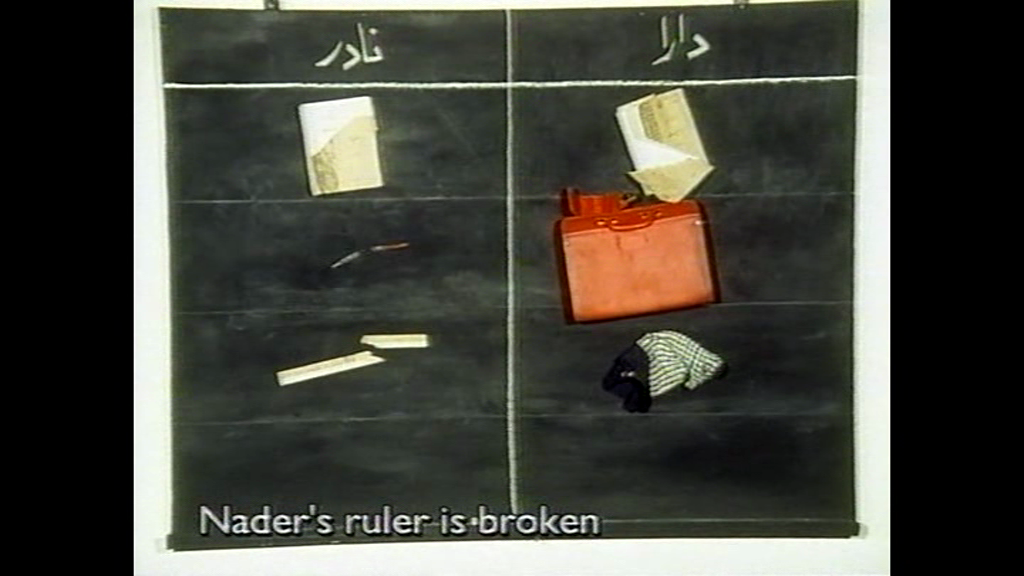

At least two shorts belong with Kiarostami’s finest work: Two Solutions for One Problem (1975) and Orderly or Disorderly (1981). Each comically explores the results of alternative forms of behavior. The first [see above photo] — showing what happens in a classroom after Doran borrows a book from Nadar and returns it with its cover torn — is like a deadpan, Bressonian restaging of one of Laurel and Hardy’s epic grudge matches: Nadar tears the cover of Doran’s book, Doran breaks Nadar’s pencil, Nadar rips Doran’s shirt, Doran breaks Nadar’s ruler, and so on, in syncopated time. An animated two-column chart on a blackboard chalks up whose objects are destroyed; then the story begins again with Doran gluing back Nadar’s book cover, the bell ringing for recess, and the boys exiting as friends.

More philosophically profound but just as hilarious, Orderly or Disorderly shows us boys leaving class, heading for a water fountain, and getting on a bus, then adults driving in a busy intersection. Each action — preceded by a film slate, accompanied by diverse off-screen comments from Kiarostami and his crew about how the shot is shaping up, and ending with “Cut!” — is shown twice, with the boys or adults behaving in orderly or disorderly fashion, and in the case of the bus-boarding we get four long takes from two separate camera angles, two of the takes containing time codes.

The shorts enhance the features in many ways. For instance, it’s hard not to see the death of a hundred-year-old woman in 1999 — the central event of The Wind Will Carry Us — as a millennial statement. Yet once we stop to think that centuries are a western idea, it becomes clear that Kiarostami is addressing global culture, not just other Iranians. So it’s significant that his very first short, Bread and Alley (1970), opens to the strains of Paul Desmond playing The Beatles’ “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” And Desmond’s alto sax is heard over a boy kicking a small box ahead of him as he hurries down an alley — anticipating not only the kicked spray-can in Close-Up, but also a would-be hitchhiker pushing a tire down a highway during most of Solution (1978), and a longer journey without music in Recess (1972).