From Sight and Sound (November 1991). -– J.R.

Play it again

________________________________________________________

Jonathan Rosenbaum

________________________________________________________

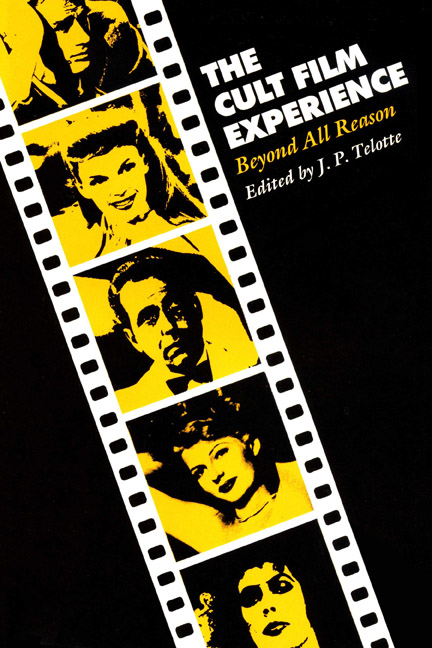

The Cult Film Experience: Beyond AII Reason

J. P. Telotte (ed), University of Texas Press,

$36, 218 pp.

Jonathan Rosenbaum

________________________________________________________

“It will be a sad day when a too smart audience will read Casablanca as conceived by Michael Curtiz after having read Calvino and Barthes”, Umberto Eco wrote in 1984. “But that day will come”. J. P. Telotte’s collection reminds us that Eco’s sad day is already well behind us — though it turns out to be Eco himself rather than Calvino or Barthes who provides the principal theoretical back-up.

Serious analysis of film cults can be traced back to a 1932 essay by Harry Alan Potamkin, but you won’t find Potamkin’s name in Telotte’s index. Indeed, apart from some cursory acknowledgments, the book fosters the impression that the arrival of film cults coincided with the burgeoning of film studies in the early 70s. This suggests that academic film study is itself an unacknowledged form of cult activity predicated on repeated viewings by a fetishistically inclined minority audience which reappropriates the film in question for its own specialized purposes.

One of these purposes is institutional, which accounts for the academics’ frequent recourse to the self- validating and ahistorical term ‘classical’ to dignify both mainstream movie-making and established film theory. Telotte, with a few hums and haws, refers to Casablanca, Beat the Devil and Judy Garland vehicles as ‘classical cult films’. Unlike the ‘midnight movies’ that constitute the book’s other major category, these are the mainstream fllms that were made and embraced (if not always cultishly) before ‘classical’ film studies got underway.

There’s an interesting contradiction in the supposed objectivity of the analyst confronting the supposed subjectivity of the cultist. Some of the best pieces here reveal a fascination with certain movies that goes beyond the decorum of classroom detachment. James Card’s informative ‘Confessions of a Casablanca Cultist: An Enthusiast Meets the Myth and Its Flaws’ addresses this contradiction head on, while Gregory A. Waller’s detailed market study of midnight movie exhibition between 1980 and 1985 in Lexington, Kentucky, where he lives and works, profits from a related proximity.

The sharp, original readings of midnight movies by Gaylyn Studlar and David Lavery betray signs of personal investment that enhance their ideological critiques, and other pieces on Casablanca by Telotte and Larry Vonalt — both of whom beg to differ with Eco, finding forms of coherence that his analysis ignores — can be interpreted indirectly as defenses waged on behalf of the film’s partisans.

Definitions of what constitutes a cult film vary widely. Timothy Corrigan nominates both The Magnificent Ambersons and 2001: A Space Odyssey, while Barry K. Grant makes room for La Cage aux folles and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. All the writers seem fascinated by the extent to which audiences can create their own canons and meanings — ‘beyond all reason’, and in seeming defiance of all the force-feeding the industry tries to impose.