From the Toronto Festival of Festivals program (September 10-19, 1981).

To quote from my long review of Pulp Fiction and Ed Wood (which can be accessed on this site), “Fourteen years ago, when the Toronto film festival still had a sidebar called ‘Buried Treasures,’ selected each year by a guest critic, I was invited to take over that slot. I put together a program called ‘Bad Movies,’ intending to play with the ambiguity of the word ‘bad’ — the only thing these films had in common, apart from the fact that I liked them, was that each of them had been pegged with that label at some point….

“This was the theory, at any rate — that all my selections were good movies that had wrongly been considered bad. But in practice, the single smash success of the series, in terms of both attendance and audience response, was Wood’s Glen or Glenda?, a film appreciated by the audience only for its badness. And since then, the evidence increasingly provided by movie fanzines — which by now far outnumber “serious” film magazines — is that among film cultists, bad movies are immensely more popular than good ones. Or, to put it in more concrete terms, at that festival the North American premiere of the penultimate, two-part masterwork of Fritz Lang, [The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Hindu Tomb], one of the greatest filmmakers who ever lived, was much less popular than the latest replay of a low-budget exploitation item by an inept amateur. Both films are campy, highly personal, and characterized by endearing technical flaws, but Wood’s unintentional hilarity counted for more than Lang’s intentional sublimity.” (Fortunately, however, the Lang diptych was picked up for an extended run by New York’s Film Forum. and I was enlisted to write the program notes for this engagement — a text which I no longer seem to have.)

Another North American premiere included in this program -– in this case, unwittingly – was Elaine May’s final cut of Mikey and Nicky, which I’d previously seen in the version alluded to here, edited by her “in radical disregard for conventional cutting continuity” (and, as I later discovered, released without her consent). To the best of my knowledge, the more conventionally edited picture that she finally put together, which I hadn’t known about until I saw it, was first shown in my Buried Treasures program.

On the whole, apart from the disproportionate popularity of Glen or Glenda?, I was quite gratified by the responses to this series. The only serious mishap was an accidental substitution of Teinosuke Kinugasa’s 1935 version of An Actor’s Revenge (that is, the original) rather than Ichikawa’s 1963 remake. (This might have come closer to being a happy accident if the print in question had been a decent and complete one.) -– J.R.

Buried Treasures (The “Bad Movie”)

Paradoxically, that ambiguous, pulpy object known as “the bad movie” has been assuming a position of increasing importance in our culture and society. This has been happening not only recently, through the services of directors like De Palma, Lucas and Spielberg, but also, more generally, through that Anglo-American tendency to shun most work that smacks of”artiness”, often including art itself.

“The bad movie,” in other words, partakes of a climate in which aesthetic and social eccentricity is more often buried than confronted. Repression of this kind can sometimes help to create a curious garden where strange and singular flowers bloom,none of them wholly acceptable or dismissableaccording to ordinary habits of taste. In an extreme case such as Glen or Glenda?, it is uncharacteristically able to proliferate and fill the lowest reaches of exploitation cinema with all the markings of an inimitable personal vision.

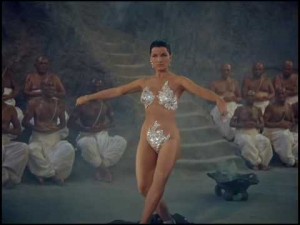

In the selection of films that I’ve made for this year’s Buried Treasures, I’ve been guided in part by personal tastes and predilections, erotic as well as intellectual, ranging from Debra Paget in the fifties (Bird of Paradise and the two Fritz Lang films ) to relatively abstract notions about the mysteries of representation (in An Actor’s Revenge, Some Call it Loving, Glen or Glenda? and Track of the Cat). But I’ve also reflected, after the fact, on the coincidence that virtually all these movies, at one time or another, have been rejected or dismissed from the can0ns of art and/or labeled, “bad” because of particular transgressions they commit in relation to traditional expectations.

This can mean belonging to a non-prestigious genre, working 0n an impoverished budget, taking up an unfashionable theme or approach, departing from certain textbook notions of correctness or slickness or coherence, or sometimes simply being unlucky enough to have been made in the wrong place or period.

There’s definitely a certain backhanded advantage to being considered a “bad movie”, just as people defined as mad have the freedom to behave like mad people — but none of the movies I’ve selected are really bad movies to me, at least not in the sense of being boring or uninteresting or untalented or anonymous. 0n one level or another — sometimes on many at once — they’re all somewhat daring and outrageous. Whether their transgressions exist through chance or design is perhaps less important that the forms of creative work and play that they can perform on – and elicit from — us.

Jonathan Rosenbaum

***

Lumière d’été

(Summer Light)

France 1943

Director Jean Grémillon

Principal Cast Pierre Brasseur, Paul Bernard,

Madeleine Benaud, Madeleine Robinson, Georges Marchal

90 minutes

Ignored in North America over the years for a variety of reasons — the fact that it was made during the French 0ccupation, by a relatively unknown French filmmaker, and was not much of a commercial success — Lumière d’été is a good example of the kind of neglected work that cries out for re-evaluation. According to French critic Bernard Eisenschitz, the filmmaker Jean Grémillon, whose career “embraces several great periods of French cinema,” directed films “not much resembling each other thanks to production problems as well as a desire to repeat nothing and to refuse nothing, whether routine melodrama or an entry in the Encyclopedie Filmée.”

The movie is remarkable on many counts — as a complex portrayal of Vichy decadence juxtaposed with the workers in a nearby coal mine; as a series of remarkable sound innovations and an intricately composed mise en scène of social interactions, suggesting the work of Jean Renoir and Jacques Becker; and as the deft execution of an ambitious Jacques Prévert script by such actors as Madeleine Renaud, Pierre Brasseut Paul Bernard, Madeleine Robinson and Marcel Levesque.

Friday 11 Sept. l1:00 a.m. Festival

***

Bird of Paradise

U.S.A. 1951

Director Delmer Daves

Production Company Twentieth Century-Fax

Producer Harmon Jones

Screenplay Delmer Daves

Cinematography Winton C. Hoch

Editor James B. Clark

Music Daniele Amfitheatrof

Principal Cast Louis Jourdan, Debra Paget, Jeff Chandler

100 minutes

Of all the Buried Treasures that I’ve selected, this 1951 color version of Bird of Paradise, directed for Fox by Delmer Daves — a remake of a 1932 South Sea tale directed by King Vidor — is the one that has the most personal resonance for me. Indeed, it helped to precipitate a full-scale religious crisis, 3 years after I saw it at the ripe old age of 8 — a process recounted in some detail in my book Moving Places, an experimental critical memoir about movies, where the film’s rediscovery serves as a kind 0f “0pen, Sesame” for myself and readers alike.

Yet I wouldn’t have included the movie here if the testimony of several friends and colleagues hadn’t persuaded me that this grim, colorful romance about miscegenation and tribal sacrifice, all set in spectacular locations, didn’t carry a distinct charge and interest of its own, quite independently of what it did to me in the early 50’s. Jeff Chandler, Louis Jourdan and Debra Paget all effectively conspire in this haunting, collective dream of a movie to evoke a carnal paradise that never was.

Saturday 12 Sept. ll:00 a.m. Festival

***

Glen or Glenda?

U.S.A. 1953

Director Edward D. Wood Jr.

Production Company Paramount Pictures

Producer George G.. Weiss

Screenplay Edward D. Wood Jr.

Cinematography William C. Thompson

Editor Bud Schelling

Principal Cast Bela Lugosi, Lyle Talbot, Daniel Davis,

Dolores Fuller, “Tommy” Haynes, Timothy Farrell

65 minutes

The only film in this selection 0f “Buried Treasures” that answers to virtually every definition of what a “bad movie” is (or can be), Glen or Glenda? is a cheap exploitati0n quickie about transvestism, made by Edward D. Wood Jr. (1922-78), an alcoholic and transvestite who also plays the title role. Reissued on a limited basis by Paramount Pictures in the U.S. last spring, it has already prompted reappraisals of Wood as a cult director with avant-garde trimmings — unquestionably one of the looniest of all low-budget auteurs, with a crazed manner inspiring affection rather than contempt.

As J. Hoberman wrote in The Village Voice, “Wood’s narrative is based on two case histories, which are recounted (with Foucaltian aptness) by a shrink to a cop. In the first, the tormented Glenn — forever ogling the lingerie displays on Hollywood Boulevard — gets married and lives happily ever after with his wife’s wardrobe. In the second, a disgruntled GI goes all the way and gets a sex-change operation. Formally, the entire film is structured to resemble an anterior parody of Mon 0ncle d’Amérique, with Bela Lugosi in the role of Professor Henri Laborit.”

Sunday 13 Sept. 11:00 a.m. Festival

***

Track of the Cat

U.S.A. 1954

Director William A. Wellman

Production Company Warner Brothers

Producer Wayne-Fellows Production

Screenplay A.I. Bezzerides from the novel by William van Tilberg Clark

Cinematography William H. Clothier

Editor Fred MacDowell

Music Roy Webb

Principal Cast Robert Mitchum, Teresa Wright, Diana Lynn, Tab Hunter, Beulah Bondi

102 minutes

Despite the effective presence of Robert Mitchum in the leading role of this movie (along with serious, often powerful work from Teresa Wright, Tab Hunter, Diana Lynn, Beulah Bondi and others), this curious experimental “Western” — adapted from a symbolic novel by William van Tilberg Clark about a cougar hunt, and directed by William Wellman — attracted relatively little notice when it was originally released in the mid-fifties. Since that time, its limited career has been even more subterranean — to a large extent, one suspects, because critics haven’t been able to figure out how to classify it. (According to David Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of Film, “the rigid color scheme” — admittedly, one of the most striking aspects of the film — “overwhelms a good subject and excellent actors.”)

Not having seen this film in years, I feel reluctant to make too many advance pronouncements regarding a work that I recall with pleasure mainly for its intricate and concentrated grasp of family tensions and its handsomely designed and integral uses of architecture in the Cinemascope frame.

Monday 14 Sept. 11:00 a.m. Festival

***

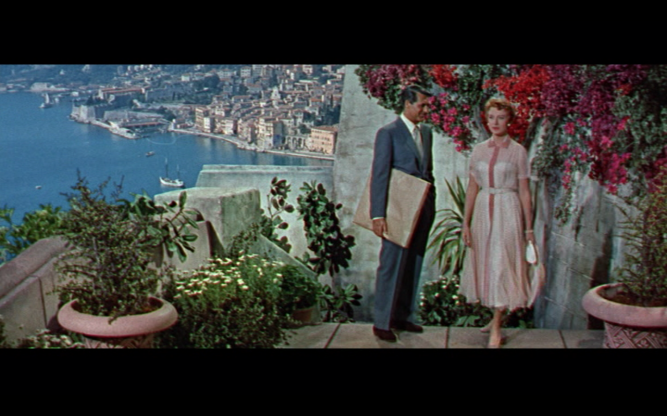

An Affair to Remember

U.S.A. 1957

Director Leo McCarey

Production Company 20th Century – Fox

Producer Jerry Wald

Screenplay Delmer Daves, McCarey from original story by Mildred Gram and McCarey

Cinematography Milton Krasner

Editor James B. Clark

Music Harry Warren, lyrics by Harold Adamson and McCarey

Principal Cast Cary Grant, Deborah Kerr, Cathleen Nesbitt, Neva Patterson, Richard Denning

115 minutes

What is it about this late film of Leo McCarey that confounds so many notions of what serious art is supposed to be? Chock full of tacky visual details, hackneyed handkerchief-wringing dramaturgy and outlandish plot improbabilities (Cary Grant

painting fruit in a garret in order to Realize His Potentialities), An Affair to Remember (which remakes McCarey’s 1939 Love Affair) achieves and then explores an emotional and spiritual depth that one might ordinarily find only in a film by Mizoguchi, Ozu or Bresson.

A firm grasp of certain primitive emotions that is comparable to D. W. Griffith’s (combined with an acute sense of ellipsis and delicate tact at certain climactic junctures) makes McCarey a master of the mode in which laughter and tears freely intermingle. And as Richard Corliss has noted, the film’s denouement “may mark the last time a writer (Delmer Daves), a director (McCarey), and a pair of actors (Grant and Deborah Kerr) dared to plumb the ludicrous shallows of the weepie and emerged deliriously triumphant — and the last time Hollywood had the strength to believe in the stuff that made it great.”

Tuesday 15 Sept. l1:00 a.m. Festival

Wednesday l6 Sept. 7:00 p.m. Revue

***

Der Tiger von Eschnapur/Das lndische Grahmal

(The Tiger of Eschnapur/The Hindu Tomb)

Germany 1959

Director Fritz Lang

Producers Louise de Masure, Eberhard Meischner

Screenplay Fritz Lang, Werner Jörg Lüddecke based on a novel by Thea von Harbou

Cinematography Richard Angst

Editor Walter Wischniewsky

Sound Clemens Titsch

Music Michel Michelet (Tiger), Clemens Titsch (Hindu Tomb)

Principal Cast Debra Paget, Paul Hubschmid, Claus Holm

150 minutes

Fritz Lang’s two penultimate features (which are based on a script and story for a two-part feature that Lang prepared with his wife Thea von Harbou in 1920, but which was then directed by the producer Joe May) have never before been seen in North America in their original versions. This is an astonishing fact if one considers that these German films were commercially successful in Europe as popular entertainments. (The U.S. version, Journey to the Lost City, was dubbed, re-edited and over 100 minutes shorter.)

Jean-Marie Straub, one of Lang’s modernist disciples, has noted that the producer of this opulent double-feature asked for a golden calf, and Lang offered him a film instead. But it’s a film about a golden calf that we call cinema — made by someone who knows more about the subject that most-and a game that is played honestly. Best of all, it returns Lang at the close of his career to his origins: the serial intrigue, charged with awe and wonder.

Wednesday 16 Sept 11:00 a.m. Festival

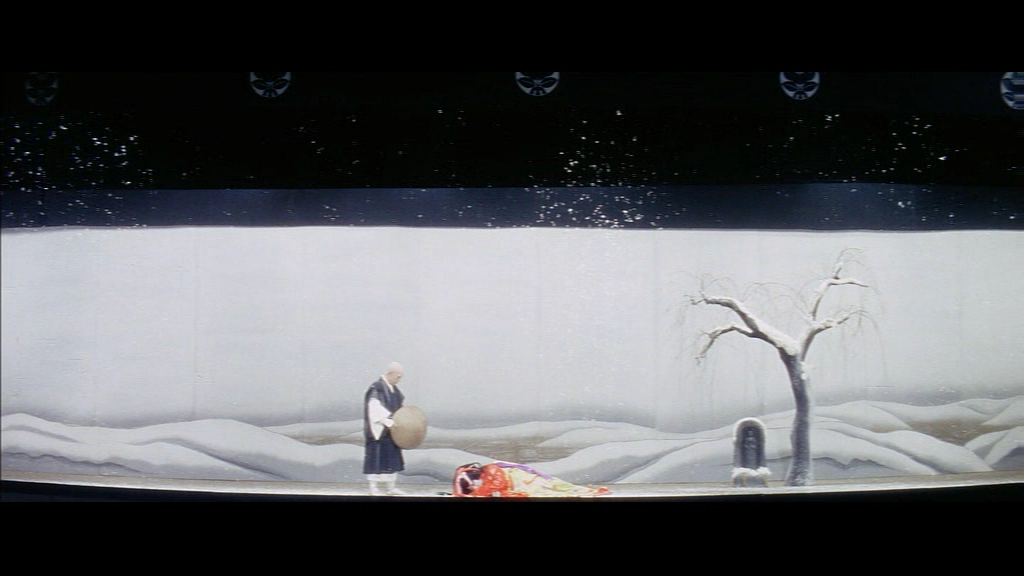

Yukinojo Henge

(An Actor’s Revenge)

Japan 1963

Director Kon lchikawa

Production Company Daiei

Screenplay Daisuke lto, Teinosuke Kinugasa, Natto Wada, from the novel Otokichi Mikami

Cinematography Setsuo Kobayashi

Music Yasushi Akutagawa

Principal Cast Kazuo Hasegawa, Fujiko Yamamoto, Ayako Wakao, Ganjiri Nakamura, Raizo lchikawa

113 minutes

One of the boldest movies ever made about the convergence of theatre and cinema (in which, paradoxically, the stagier it gets, the more cinematic it becomes), Kon lchikawa’s highly eccentric masterpiece, shot in dazzling color, was one of the favorite films of the late Nicholas Ray. Based on a rickety melodramatic warhorse and starring an aging matinee idol, Kazuo Hasegawa, An Actor’s Revenge improbably suggests William Shakespeare as well as Walt Disney (the latter Ichikawa’s greatest single influence, by his own admission) in its brilliant pyrotechnics.

In an intriguing double role, Hasegawa plays both an oyama (female impersonator) who’s an experienced swordsman and a clever petty thief. A recurring contemporary jazz score and an almost continual shift of gears between different levels of reality and artifice make this, in the words of film theorist Noël Burch, “one of the first important instances in the Japanese cinema of the conjunction between an objective ‘Brechtianism’ of the traditional stage and the influence of the modern cinema and theatre on traditions as diverse as Brecht, Elizabethan drama and the comic strip.”

Thursday 17 Sept. 11:00 a.m. Festival

***

Some Call it Loving

U.S.A. 1973

Director James B. Harris

Production Company James B. Harris Production

Producer James B. Harris

Screenplay James B. Harris, from the story “Sleeping Beauty” by John Collier

Cinematography Mario Tossi

Editor Paul Jasiukonis

Music Richard Hazard with song by Bob Harris

Principal Cast Zalman King, Carol White, Tisa Farrow, Richard Pryor, Veronica Anderson

103 minutes

“To wake the Sleeping Beauty,” declares a lewd carnival sideshow barker. “you run the risk of being awakened yourself.” Succinctly summing up the contradictions of the Hollywood dream factory regarding desire and illusion, this haunting, off-beat feature, freely adapted from a John Collier story, found an audience in Paris eight years ago, but attracted little attention on this side of the Atlantic.

Its deliberately dreamlike plot involves a wealthy, white jazz saxophonist (Zalman King), two women (Carol White, Veronica Anderson) who willingly act out his erotic fantasies, a dying black derelict who worships him (Richard Pryor, in a brilliant early performance), and a real-live Sleeping Beauty (Tisa Farrow) whom he purchases from a carnival sideshow. The second feature directed by Kubrick’s former producer (on The Killing, Paths of Glory and Lolita) James B. Harris — preceded by The Bedford Incident (1965), and followed by the forthcoming Fast-Walking — Some Call it Loving isn’t for every taste. Its theme and style is one of disenchanted lyricism in relation to the solipsistic enclosures of dreams, placed on the screen with a hypnotic grace that suggests a circular musical lament.

Friday l8 Sept. 11:00 a.m. Festival

***

Mikey and Nicky

U.S.A. 1976

Director Elaine May

Production Company Paramount Studios

Producers Michael Hausman, Bud Austin

Screenplay Elaine May

Cinematography Victor J. Kemper

Editor John Carter

Sound Richard Vorisek, Christopher Newman, Larry Jost

Music John Strauss

Principal Cast Peter Falk, John Cassavetes, Ned Beatty, Rose Arrick, Carol Grace, William Hickey

118 minutes

There are few serious films quite as maudit in recent American cinema than Elaine May’s controversial third feature (and last to date), an unsettling drama about love and betrayal between a couple of Philadelphia gangsters (John Cassavetes and Peter Falk during one long, grueling and paranoid night. While at first glance this misanthropic movie seems to be extending the improvisational methods of John Cassavetes as a director in movies like Husbands, Mikey and Nicky is in fact a tightly-scripted view of hell that was edited by May in radical disregard for conventional cutting continuity.

Difficult to relate to in any ordinary fashion yet impossible to forget, May’s ferocious (and ferociously personal) assault on the middle-class is much more corrosive than anything ever dreamed up by Fassbinder. If The Heartbreak Kid were her Foolish Wives, this is surely her Greed -– and perhaps the most frightening portrait of capitalism that American cinema has given us since Eric von Stroheim’s masterpiece. (Stanley Kauffmann calls it an “odd, biting, grinning, sideways-scuttling rodent of a picture” and “the best film that I know by an American woman.”)

Saturday 19 Sept. 11:00 a.m. Festival