From Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1974 (Vol. 41, No. 489). Postscript: Thanks (once again!) to Ehsan Khoshbakht for providing me with an extra illustration for this review. — J.R.

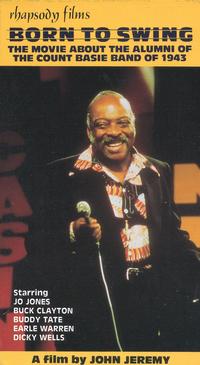

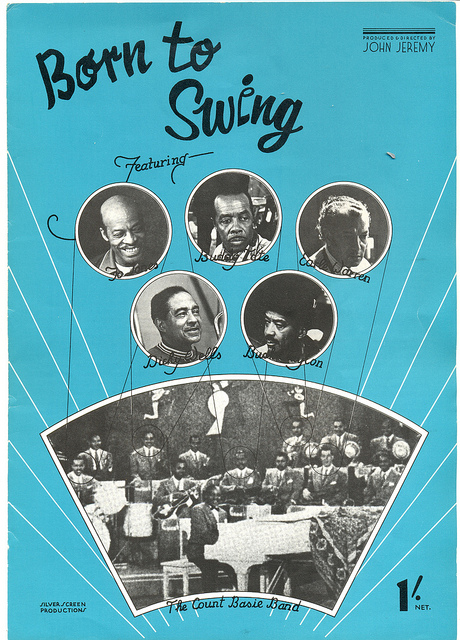

Born to Swing

Great Britain, 1973

Director: John Jeremy

Dist–TCB. p.c–Silverscreen Productions. p–John Jeremy. p. manager—

Angus Trowbridge. sc–John Jeremy. ph–Peter Davis, Tohru Nakamura.

photographs–Ernie Smith, Valerie Wilmer. ed–John Jererny. m–Buddy

Tate, Earle Warren, Joe Newman, Dicky Wells, Eddie Durham, Snub

Mosley, Gene Ramey, Tommy Flanagan, Jo Jones, The Count Basie

Band (1943). m. rec—Fred Miller. sd. rec—Ron Yoshida. sd. re-rec—

Hugh Strain. narrator–Humphrey Lyttelton. with–Buck Clayton, John

Hammond, Andy Kirk, Jo Jones, Albert McCarthy, Gene Krupa, Snub

Mosley, Joe Newman, Buddy Tate, Earle Warren, Dicky Wells. 1,773 ft.

49 mins. (16 mm.).

This engaging jazz film has both a general subject and a specific

one. Generally, it is about American swing music of the past;

specifically, its main focus is six veterans of Count Basie’s band in

the present. Interspersed with a 1943 clip of the Basie band inspiring

some athletic dancers are album covers, flurries of sheet music,

neon signs, and a string of short reminiscences: by Andy Kirk,

about his stint with the Eleven Clouds of Joy; Snub Mosley, about

New York in the Thirties; the doorman at Jimmy Ryan’s, about

52nd Street; Gene Krupa, mainly about himself. Then comes jazz

producer John Hammond, who recalls hearing Basie as a second

pianist in Benny Moten’s band, thereby leading us into the film

proper — the contemporary lives of six Basie alumni, intercut with a

studio session in which five of them participate. These six lives are

disparate indeed, and the film runs a brisk relay from one to the

next. Dicky Wells lives in Harlem and works as a messenger on

Wall Street (some clever crosscutting from trombone slide-work in

the session to mail-sorting on the job). Buddy Tate, appreciably

more affluent, is seen at his country home chatting about old times

and current booking dates. Buck Clayton explains his abandonment

of the trumpet on doctor’s orders, and is seen as a visitor at Joe

Newman’s trumpet class in Harlem; a little lecture by Newman

about tone explodes into a beautiful demonstration he gives at the

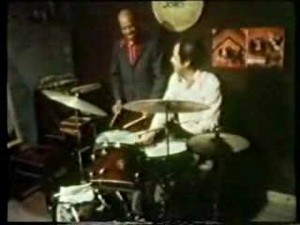

session. Next comes Jo Jones, followed into his drum shop where

he is observed teaching fancy percussion tricks to novices. Finally

we move back again from security to scuffling, and hear Earle

Warren describe a current commercial job dictated by a family

illness. Only when we follow Warren back to the studio reunion does

the film settle down to some extended music, and the effect is

admirably climactic. John Jeremy has a way of editing to the music

that proves he likes to listen to it. But with so much social, cultural

and musical material to get through in less than an hour, one

occasionally regrets the scatter-shot pace, the bite-size definitions

of style and milieu, and the necessity of paring down the historical

context to a narrow abbreviation. Discussing Thirties swing

inevitably leads to Basie, but virtually to omit Lester Young and his

influence from the survey is a bit like discussing Paramount over the

same period by centering on Lubitsch and leaving out Sternberg.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM