From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977. — J.R.

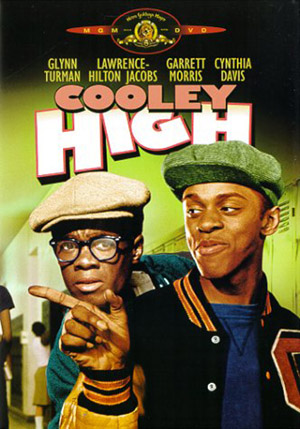

Cooley High

U.S.A.,1975

Director: Michael Schultz

Chicago, 1964. Cochise, Preach, Pooter and another friend, students at Edwin G. Cooley Vocational High School, sneak out of class one Friday and visit the Lincoln Park Zoo; afterwards they play basketball, and Preach, who has been dating Sandra, flirts with the aloof Brenda. At home, Preach finds a letter informing him that he has received a scholarship; that night, he attends a party with his friends and re-encounters Brenda, who warms to him when she discovers his interest in poetry. After the party is broken up by a fight provoked by Damon, Preach and Cochise join Stone and Robert to go joyriding in a stolen car; Preach takes the wheel and drives recklessly, eluding the police after an extended chase. On Saturday, Preach and his friends study briefly for a history exam before going to the movies, fleeing the cinema after Pooter unwittingly provokes a fight. On Sunday, Preach takes Brenda home and they make love; after he casually lets drop that he bet Cochise money that he could sleep with her, she runs away and the next day at school kisses him in front of Sandra. Just before their history exam, Preach and Cochise are arrested for car theft. Mr. Mason. their teacher, mentioning Preach’s scholarship, persuades an officer to let them off but Stone and Robert, who are also picked up, are prosecuted, and assume that Preach and Cochise informed on them. After discovering that Cochise has slept with Sandra and leaving him in anger, Preach flees from Damon, Stone and Robert and meets Brenda under the El tracks; learning that his pursuers have caught up with Cochise, he returns to find that his friend has been beaten to death . . . After watching Cochise’s funeral from a distance. Preach approaches the grave site alone to read a farewell poem, and then sets out on the road. An epilogue reports that he fulfilled his ambition to become a successful Hollywood scriptwriter: Brenda became a librarian, married and had three children; Stone and Robert were killed in a hold-up in1966; Damon wound up as an army sergeant and Pooter as a factory worker.

More ambitious and less successful than his exuberant Car Wash, Michael Schultz’s first feature can be viewed with hindsight as the promising debut of a very talented director, intermittently doing what he can with an uneven and somewhat routine script. Previously known for his work in the New York Theatre (where he directed the Negro Ensemble Company) and TV, Schultz is clearly someone whose humor, handling of actors and spirited kaleidoscopic rhythms have a distinctive flavor all their own. And apart from such recognizably ‘personal’ trademarks as a taste for scatological gags and a flair for projecting the more inventive inflections of black American speech, the mere fact that his two features have elicited such strong communal responses from black audiences –- expressions of collective delight which are rare commodities in contemporary commercial cinema, which generally traffics in diverse forms of mutual estrangement — makes him a figure and a phenomenon to be reckoned with. Cooley High, like Car Wash, begins as an irreverent, free-floating comedy and develops its more ‘serious’ concerns (along with its plot) rather belatedly, almost as if they were after-thoughts. Considered in isolation, Eric Monte’s seemingly autobiographical script is largely a string of archetypal high school capers in the American Graffiti manner, complete with hit singles in the background and ironic post-mortems on its major characters in an appended epilogue. Like many first novels, the film mainly falters by showing structural uncertainties about how to organize and distribute its wealth of material; characters as important as Mr. Mason and Preach’s mother are allowed to emerge too late in the proceedings and too briefly, while most of the purely stock scenes and situations — the fights, the car chase, Preach’s love-making with Brenda (rendered cloyingly with strings, piano, flute and slow dissolves) — are unnecessarily protracted, like exploitation reflexes. Perhaps the film’s strongest asset is Glynn Turman’s performance as Preach: the ambivalent and often cumbersome relationship he has with his glasses, the alternating bouts of teenage braggadocio (quoting Walter Benton’s poetry to Brenda) and sheer terror (when she announces, after getting into bed, that she’s a virgin), and the throwaway delivery of his mawkish poem at Cochise’s grave (before he literally throws away the poem, by tossing it into the grave) are all superbly realized. Individually and collectively, such notations serve to outline a somewhat less than heroic protagonist, whose clearest moment of self-realization seems to come when he acknowledges — at the self-same graveside — that he expects to succeed in Hollywood because of what he knows about lying and cheating. Coupled with this portrait are wonderful glancing insights into the milieu — well served by the actors involved -– most of which figure as isolated moments: Mason’s plea on Preach’s behalf to a friendly police officer, delivered while the two men casually share a joint; Preach’s mother’s exasperated and threatening command to her son to fetch her “the belt”, before she promptly falls asleep in a chair. Implicit in the plot and epilogue is a comparable wisdom about the possibilities and limits of Preach’s world, however incompletely the film manages to articulate it while going through more conventional paces.