Posted in Moving Image Source, December 1, 2009. This is the second time I wrote at length about White Hunter, Black Heart, and this essay was reprinted in Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinema; the earlier piece, written 19 years earlier, is available here. [August 31 footnote: After watching Eastwood’s embarrassing and often fumbling impromptu speech at the Republican National Convention last night, I treasure his performance in this spectacularly underrated movie even more.] — J.R.

“It’s the film of a free man.” Roberto Rossellini’s celebrated defense of Charlie Chaplin’s most despised film, A King in New York (1957) — a film so reviled that it goes unmentioned in Chaplin’s 1964 autobiography — is a sentence that frequently comes to mind about some of the features directed by Clint Eastwood, especially over the past couple of decades. Eastwood has in fact carved out a singular niche for himself that affords him the sort of artistic and conceptual freedom that no one else in Hollywood can claim. Starting with the fact that he doesn’t test-market his movies and indulge in the sort of hasty post-production revisions that limit the range of his colleagues, he’s a director who can choose both his subjects and how he deals with them.

In some respects, of course, comparing Eastwood’s freedom with Chaplin’s is highly dubious — even if one can find a few parallels that go beyond their status as producer-director-stars, such as the fact that both have composed music for their own films. Eastwood, unlike Chaplin, isn’t a writer and remains fundamentally at the mercy of his scripts, and he doesn’t own the negatives of his own pictures. But if one compares the relative freedom of each filmmaker in his prime with that of his commercial contemporaries, the similarities become somewhat more meaningful.

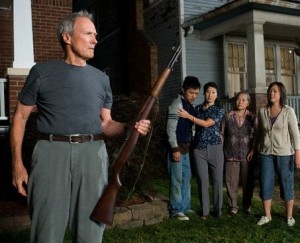

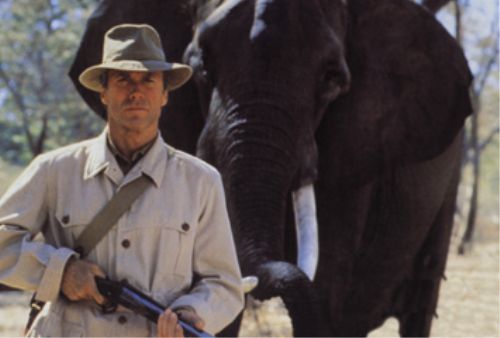

In part because of Eastwood’s conservative persona, he can offer political critiques of certain aspects of the American character, both as an actor and as a director, that wouldn’t be tolerated from anyone else in the industry. He can seriously question the chauvinistic and propagandistic uses of a famous Iwo Jima photograph (Flags of Our Fathers, 2006) and counter many popular notions about Japanese soldiers during the same war (Letters From Iwo Jima, 2006), implicitly undermining some of the patriotic excuses for the recent American occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan. And using his own persona as a star, he can launch detailed assaults on racism in some films (most recently in last year’s Gran Torino), on macho behavior in others (including such relatively commercial projects as Blood Work) and on both in White Hunter, Black Heart (1990).

The critique offered in this underrated and frequently misunderstood Eastwood film goes beyond egocentric notions of masculinity to encompass certain forms of American arrogance and imperialism, even though the ostensible target is a famous all-American liberal, filmmaker John Huston. Peter Viertel’s 1953 novel of the same title is a transparent roman à clef about his own experience of working with Huston as a screenwriter on The African Queen — a job that for Huston was mainly an excuse to indulge in his obsession with becoming a big-game hunter and bagging an elephant on location, before shooting on the film even started.

Viertel — son of the famous Hollywood Jewish-émigré intellectuals Salka (Greta Garbo’s best friend) and Berthold Viertel, who published his first novel when he was 18 and later married Deborah Kerr — was already an old pal of Huston’s, having worked with him on We Were Strangers (1949), and he came on board more as a writer and friend than as someone with much taste for killing animals himself. The degree to which his friendship with Huston became tested by this encounter is one of the book’s key themes, and Viertel’s transparency is reflected even in the characters’ names, Pete Verrill and John Wilson.

In Viertel’s 1991 memoir, Dangerous Friends: Hemingway, Huston and Others (a book that in recent years has become a pricey collectors’ item), he notes that both Hemingway and Irwin Shaw told him that they regarded this transparency as a mistake and that he eventually came to agree with them: “Had I changed the names of my leading characters, my novel would probably have been judged on its own merits rather than as a scandalous ‘knock piece,’ which was how it was received by a majority of critics.” Less critical at the time was Huston himself, who suggested the specific and devastatingly tragic, anti-imperialist ending that Viertel wound up using, after reading an incomplete version — which he praised profusely, in spite of its unflattering portrait of himself — during the shooting of Moulin Rouge. (He also signed a release after reading the novel’s final typescript.) However, the novel goes unmentioned in Huston’s own 1980 memoir, An Open Book, and Viertel speculates that his friend privately nursed a “long-dormant bitterness” about it.

The portrait of Huston that emerges as both a monstre sacré and a vain nihilist in both the novel and movie ultimately has bearing on his unevenness as a director (passing back and forth repeatedly between serious work and hack jobs), his misanthropic existentialism (often reflected in the futility of his characters’ fates), and his macho pretensions as well as some of his leftist positions. By the end of the story, he’s largely exposed as a destructive ugly American who poisons everything around him, in spite of his charming impudence. And his seeming lucidity about himself often comes across as simple confusion. When Pete charges Wilson with committing a crime against nature by going after elephants, Wilson counters that it’s worse than a crime, it’s a sin — “the only sin you can buy a license for and then go out and commit. And that’s why I want to do it before I do anything else. You understand?” It’s a sentiment worthy of an Ahab. But sin is a meaningless concept for an atheist, and even Wilson/Huston’s cosmic pessimism and cynicism are ultimately compromised by this form of defiance. (This may account for why Wise Blood — an atheistic take on the gallows humor of a true believer, Flannery O’Connor — seems to me the best of Huston’s films, encompassing the full reach of his passionate ambivalence.)

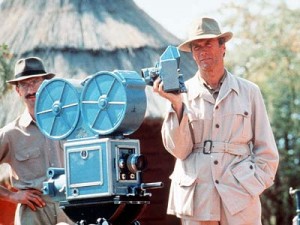

Adapting White Hunter, Black Heart for the screen had been a long-term project. Ray Bradbury, who also worked for Huston (on the 1956 Moby Dick), was commissioned to write an early screenplay in 1959, and the one that Eastwood used three decades later credits Viertel himself and directors James Bridges (Urban Cowboy) and Burt Kennedy (Welcome to Hard Times), in that order. It’s an unusually faithful adaptation, and the fact that Eastwood cast himself as John Wilson appears to be the source of most of the problems many have had with the film. For me, it’s one of the chief sources of its brilliance.

Auteurist issues are at the center of this debate, as they are with the no less contested A.I. Artificial Intelligence — which is usually read as a Steven Spielberg film and occasionally read as a Stanley Kubrick film, but is generally thought to be indigestible as both at the same time. The auteurist issues in this case, however, relate to the actorly personas of Huston and Eastwood, which are respectively hammy/rhetorical and minimalist/terse. If Eastwood as an actor has to be judged exclusively as a precise impersonator of Huston, the inadequacy of the vocal and facial equipment he brings to this task is inescapable — as inescapable, one might argue, as the inadequacy of Spielberg as a directorial impersonator of Kubrick.

But if one shifts one’s expectations and evaluates Eastwood as an interpreter of and commentator on Huston’s persona in relation to his own — a dialectical meditation on Huston as well as himself that is both critique and appreciation — the nature of his achievement changes. He offers in effect a Brechtian performance, especially if one thinks of Brecht’s own description of how he wanted Charles Laughton to play the title role in his Galileo (as set down in his “Small Organum for the Theater”): “The actor appears on stage in a double role, as Laughton and as Galileo; the showman Laughton does not disappear in the Galileo he is showing; Laughton is actually there, standing on the stage and showing us what he imagines Galileo to have been.”

How does this function in the film? As a running commentary on his two subjects, Huston and himself — the ruminations and questions (rather than the answers) of a free man. In many ways the centerpiece of both the novel and the movie is a scene in Entebbe, Uganda, at the Sabena Hotel’s outdoor restaurant, where Wilson first verbally abuses a woman he is trying to seduce because of her blatant anti-Semitism and then picks a protracted fight with the headwaiter after observing him mistreat a black African waiter for dropping a tray. This scene derives from Huston’s own account to Viertel of an hour-long drunken fistfight he started with Errol Flynn in David O. Selznick’s garden in 1945 after Flynn made a scurrilous comment about a woman Huston knew. (It landed both men in separate hospitals, Huston with a broken nose and Flynn with two broken ribs, and Huston devotes over a page to the incident in An Open Book, describing it with obvious relish.) The novel makes this far more interesting by celebrating Huston’s grandiloquence in denouncing the woman for her anti-Semitism and then making us acutely uncomfortable about the fistfight. (When Pete tries to hold him back, Wilson says, “Let go. We’ve fought one bout for the kikes. This is the main event…for the niggers.”) And Eastwood improves on the novel by making his own performance at once a flashy embodiment, a scathing ridicule, and an open questioning of this kind of behavior (a potent mixture that he also employs, minus the questioning, as Walt Kowalski, the racist hero of Gran Torino). At the end of his hunt, ready to embark on another kind of shooting, Wilson discovers that he’s an even more murderous enemy of black Africans than a racist headwaiter, and the film asks us to ponder why and how this should be so.

One Chaplinesque aspect of this kind of star performance is that it risks turning virtually everyone else in the story into a prop: Walt Kowalski’s dead and unseen wife in Gran Torino never comes alive for us even as an absence, and we tend to ignore the functional performances of everyone else in White Hunter, Black Heart, including Jeff Fahey as Pete. But Eastwood turns even this limitation into a virtue by finally fusing himself and Huston/Wilson into the same figure in the film’s final shot, as he starts to direct — terse and rhetorical, defeated and in control — with a single word: “Action.”