From Oui (March 1975). I no longer recall whether or not the editors changed the wording of some of my questions; I suspect that in many cases they did. Because of the length of this interview, I’m posting it in two parts. -– J.R.

Excerpted from the Introduction [obviously not by me]:

“Jonathan Rosenbaum interviewed Morrissey in Paris, shortly after the director had completed his latest films [Flesh for Frankenstein and Blood for Dracula aka Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and Andy Warhol’s Dracula (sic, sic), only the second of which I’ve ever seen, then or since. -– J.R.] He described being greeted at the door by Nico, of the original and most durable Factory regulars:

“Nico entertained me with comparisons of Paris and Los Angeles, while Morrissey served me orange soda from his refrigerator,” he said. “Morrissey enjoys talking –– the interview was nearly a monologue –- and he speaks in a slightly nasal tone, a cross between Brando and the Bronx.”

OUI: Let’s talk about political content. Your films are usually much more poignant and compassionate than you yourself are reputed to be. In some quarters of the film world, you have a political reputation that might be compared to Ronald Reagan’s.

MORRISSEY: I don’t know much about Reagan. He’s denounced for putting down student uprisings, but to me that sounds good.

OUI: You don’t like students?

MORRISSEY: Students in any society shouldn’t be listened to. They stand in line in the mud at rock festivals, like cattle. They’ll get in a queue for a movie the way cockroaches go to the corner of a room. The quality of education they get in the United States is worse than appalling. It’s a big joke.

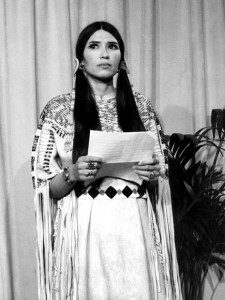

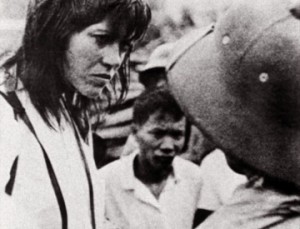

OUI: Do you feel that leftist actors’ and actresses’ opinions count for anything? Do you admire, say, the politics of Brando or Jane Fonda?

MORRISSEY: Well, they arouse people’s sympathy for good causes, and there’s no harm in that. But I don’t think they’re very well informed on broad political issues. I like what John Wayne says, and whenever he talks, I find that I agree with him 100 percent. One of his great remarks was that he didn’t think Europeans or Americans had done a terrible crime to the Indians by taking over their land. As you know, the liberal bullshit is that Americans are guilty, that they’re the greatest criminals on earth. But Europeans were crowded and starving and had to go somewhere. They needed land and the Indians weren’t using theirs. If that kind of liberal junk thinking had prevailed 300 years ago, Europe would be collapsing and America wouldn’t exist. It would be a wasteland like Africa.

Just because some colored people have been sitting on a piece of land for hundreds of years doesn’t mean they have complete control over it. Nationalism, in that sense, is stupid. And now a bunch of Arabs are sitting on a piece of land that’s valuable to the entire world, and it really isn’t their land. If the world needs oil or food, that oil or food should be given to the world. The Arabs will be so rich soon that they’ll be able to buy up every country in the world. It’s a ridiculous situation that allows that sort of thing to happen. Instead of wandering around, taking drugs and not knowing what to do with themselves, American hippie kids should go to a country, colonize it and make a new civilization there.

OUI: Do you mean Americanize it?

MORRISSEY: Americanize it, Europeanize it, Irishize it! Certainly, to Americanize it would be the best thing; America has the best civilization in the world, as far as improvements and everything are concerned.

OUI: Come on. Do you really think that New York is a civilized city with the best of everything?

MORRTSSEY: New York is inexcusable. I always liked New York, until I spent a month in Beverly Hills, where there were no drug addicts sitting on the sidewalks, urinating in the doorways. In California, if you break a law, they’ll arrest you, they’ll hold you in jail and they might actually fine you or put you in prison. But in New York, you can rob or destroy or deface or mug and there’s no penalty, because you can fill out your name on a form and they let you go. If you commit a crime in New York, you don’t get punished, you get “understood”. Every politician who runs for office says we must spend more money not on stopping crime but on ”understanding the problem.” Meaning kiss the ass of the criminal.

OUI: But in some of your films, you’ve shown certain kinds of criminals — at least street people and drug addicts — sympathetically.

MORRISSEY: A human being is a sympathetic entity. No matter how terrible a person might be, someone with an artist’s point of view will try to render his individuality without condescension or contempt. That’s the natural function of a dramatist. The movies I’ve made have no connection with what I’m talking about now. They don’t say, ”Do this,” or “Don’t do that.” They portray a kind of emptiness in people who are living through a transitional cultural period when they don’t know who they are or what to do.

OUI: How are problems solved when people don’t know what to do?

MORRISSEY: A politician who’s permitted to do something on his own — instead of being hampered by the media — might be able to do something. Human beings are always capable of resolving problems. But now, problems go to committee or to the media. I still look to the individual for solutions. Like in a movie, you want an individual to be an individual.

OUI: Nixon, as Watergate has shown, certainly tried to do something on his own, resolving problems as an individual.

MORRISSEY: The stupidest person on The Dating Game has more personality than that pathetic dope. You have to have character to make a good novel or a good movie or to be a good politician. Nixon just didn’t have it. And the newsmen kept obscuring that fact. Those zombies gave both sides of the story without any indication of what they thought personally. The people in the street began to lose sight of what a lying little creep Nixon was, because nobody on television said he was a lying little creep. People are confused by this double standard of nonsense impartiality, which has deprived them of the truth.

OUI: Are there any politicians whom you admire?

MORRISSEY: Truman, for one. He was not only a great man but one of our greatest Presidents. He was plainspoken, candid and blunt, but he sounded believable, in the sense that he had style and flavor and a strength to his voice. He was absolutely everything that Nixon was not. Senator Edward Kennedy is another politician I admire. He speaks well, extemporaneously, and with a great deal of sincerity. He’s able to make an audience listen to him and can actually arouse them. A person like that is hated by the media, which constantly put him down.

OUl: But doesn’t a politician who is not kept in check by one means or another develop too much power? For example, Nixon, at one point in his tenure, had so much power that he waged war without the consent of Congress. Do you think any President should have that kind of power?

MORRlSSEY: If I liked the person, I wouldn’t mind. I think an intelligent President should be able to conduct a war if he wants to. I’d prefer to have one person do it rather than a committee. I don’t believe in this democratic government we have in the United States. I think it’s a lot of junk. The democratic system gave us Eisenhower and Nixon. Besides, it’s a pain in the neck to have to think about politics. I hate to read my newspaper and find out about all the horrible things that are going on. I’d like to think that there were someone hired by the system, a good politician, who would run the business of government intelligently, and I would not have to be agonized every day by the press.

OUl: You sound like you’re advocating dictatorship. Such a person, with so much power, might very well censor your films.

MORRISSEY: Well, in England, there was one man, John Trevelyan, who did all the censoring. He was very intelligent, and if he didn’t like a film, it wasn’t shown. You could appeal a decision to him — maybe he’d understand and change his mind, and maybe he wouldn’t. But that’s much better than what we have in the U. S., where some crackpot in a city can bring a complaint and the movie is judged obscene.

OUI: So you approve of the censorship of your own films?

MORRISSEY: No, it’s just something that happens. It’s something you can understand. Italy, for example, has censored my films a great deal. But it’s a Catholic country — they want certain standards in their cinema. There’s some validity to their position; they’re not just hateful crackpots.

OUI: Would you censor films such as Deep Throat or The Devil in Miss Jones?

MORRISSEY: I didn’t see either one, but if you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all. Presumably, they serve some kind of therapeutic function. Maybe they do, but the argument for censorship is that kids pass the theaters in neighborhoods that book these films and wonder what’s going on inside. Older kids sneak in and tell them. Certainly, these films influence community standards. And there is some basis to the fear that these things weaken the institution of the family, at a time when we need to preserve the society. Trevelyan’s position was sensible: “England has a particular character, which we want to preserve, and because we are physically able to keep sex movies out of our island, we do. They’re showing them in Scandinavia and America, and whether they deteriorate the community will take 20 or 30 years to determine. We don’t want to be guinea pigs. We’ll let these countries experiment while we take a conservative position and wait and see.” I thought that was extremely intelligent.

OUl: Do you also approve of political censorship?

MORRISSEY: I’ve never heard of political censorship in the United States. There isn’t such a thing — except for the suppression of individuality. And in France and Italy, the kids who think that communism is a great thing are completely blind to the fact that they have such incredible censorship in China and Russia.

But all the political things I talk about aren’t things you can exemplify in a film. They’re things that have to be talked about publicly.

OUl: Doesn’t the idea of a political film interest you at all?

MORRISSEY: No, I can’t even think of a good political film. Z is just Mission: Impossible with a jazzed-up score. What can you say? You shouldn’t kill people to take over a government. So what else is new? On the Waterfront was one of the best films ever made and it was hurt by becoming a political statement at the end. Whether the Brando character should testify or not dated the film, and now that aspect seems silly and melodramatic. You just overlook it. I think any political element in a film, to the extent that it is political, becomes outdated very quickly.

Basically, I have a comic outlook on things. But there are a lot of scenes in Flesh, Trash and Heat that aren’t comic. Women in Revolt, which to me is one of the best films ever made, is completely comic. People turned their noses up at it, yet it’s very funny. It’s filled with interesting ideas that aren’t pushed in the face of the audience, and it’s brilliantly performed by great performers. There are so many paradoxes in that film: female impersonators talking about the problems of women’s liberation, how women are dominated and dependent in society. But when you think of it, female impersonators are the most independent people in the world. It was really interesting, because the audience saw a man being a woman and couldn’t tell what was real and what wasn’t.

OUI: Will you use characters in drag again?

MORRISSEY: No; once RCA started making millions off commercialized drag queens, that became dreary and passé.

OUI: Do you envision a time when what you’re doing in films will be dreary and passé?

MORRISSEY: Well, by leaving out scripts, we come up with so much that’s worth listening to. By avoiding issues, you hit upon issues; but by going after them, you lose them. It’s difficult to balance, juggling with that paradox when you make films that way. Andy’s already stopped making them and I’m on the verge of stopping.