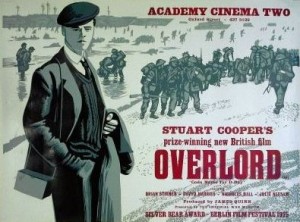

Criterion has just released Overlord on Blue-Ray. Here are my two separate reviews of the film, written over three decades apart — for Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1975, Vol. 42, No. 500, and for the Chicago Reader, June 2, 2006. — J.R.

Overlord

Great Britain. 1975

Director: Stuart Cooper

Cert–A. dist-EMI. p.c–Joswend. p–James Quinn. p. manager—

Michael Guest. sc–Stuart Cooper, Christopher Hudson. ph–John

Alcott. optical effects–Vee Films. ed–Jonathan Gili. a.d–Michael

Moody, Barry Kitts. m–Partl Glass. songs–“The Lambeth Walk” by

Douglas Furber, Noel Gay; “We Don’t Know Where We’re Going” by

Ralph Butler, Noel Gay, sung by Nick Curtis. costume advice–Laurie

Milner. titles–Ann Hechle. sd. ed–Alan Be1l. sd. rec–Tony Jackson.

sd. re-rec–Gerry Humphries. l.p–Brian Stirner (Tom), Davyd Harries

(Jack), Nicholas Ball (Arthur), Julie Neesam (Girl), Sam Sewell (Trained

Soldier), John Franklyn-Robbins (Dad), Stella Tanner (Mum), Harry

Shacklock (Station-master), David Scheuer (Medical Officer), Ian Liston

(Barrack Guard), Lorna Lewis (Prostitute), Stephen Riddle (Dead German

Soldier), Jack Le White (Barman), Mark Penfold (Photographer), Micaela

Minelli (Little Girl), Elsa Minelli (Little Girl’s Mother). 7,504 ft. 83 mins.

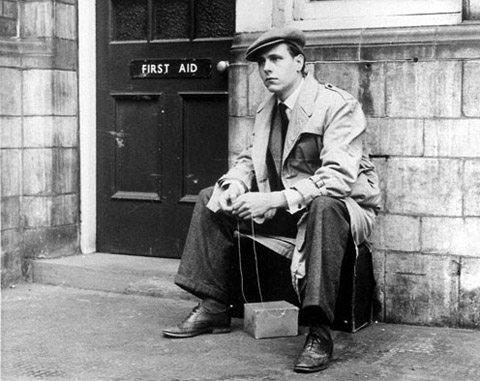

England, 1944. Receiving his call-up papers, Tom says goodbye to his

parents and his cocker spaniel Tina before boarding a train for his camp.

Bewildered and beleaguered by the ordeals and rituals of basic training,

he befriends Arthur, a fellow recruit, who talks about his girlfriend back

home and encourages Tom to enjoy a little love-life when and where he

can. In a cinema, Tom is importuned by a prostitute but flees from her.

With the other men, he is taken to the coast for further training and to

become part of the general Allied build-upfor the Normandy invasion.

In a village dance hall he meets a girl whom he takes for a walk, kisses

and promises to see again. But soon afterwards he is taken away by

truck with his mates Arthur and Jack to the marshalling area.

Reaching the age of twenty-one and having premonitions that he

won’t survive the war, Tom writes a letter to his parents, makes out

a will, and has his hair cut and his photograph taken. Just before

D-Day, he burns all his personal papers with the other men. On a

landing craft with Jack and Arthur, he recalls a visit with the latter

to a run-down deserted theatre where a little girl was singing, and

imagines being undressed by the girl he met in the village and

making love to her. On the very point of landing in Normandy, he

is killed.

As Nuit et Brouillard and Les Carabiniers have each demonstrated

in their vastly different ways, the juxtaposition of newsreel material

and freshly created footage can go a long way towards defining

both a distance from and a proximity to the brutal facts of modern

war without in any way compromising their horror. Perhaps the

essential problem with Overlord — a semi-fictional documentary

intermixing a staged personal story with archive selections from the

Imperial War Museum — is the reductive quality of the fiction cut

into the relatively impersonal documentation, an Everyman-as-

Anyone tale conjuring up a sentimentality fatal to any persuasive

reckoning of D-Day and its preliminaries, either on an individual

or a collective level. Despite some conscientious and intermittently

successful efforts to adapt the tones and grain of the new material to

its newsreel counterpart, the dialogue is so patently uninspired and

clichéd (“I hate this war” “You’ll get through -– “ “It’s not that, it’s

me girl –“; “I wish I’d met you before. We’ve so little time now — ”

“Why do you say that?” “I don’t know… it’s just a feeling — “)

that any trace of complexity in feeling or attitude is instantly

jettisoned for the sake of simple platitude. The deliberate obfuscation

of the relation between documentary and staged material often

becomes troubling in the use of sound as well as image: quite apart

from some obtrusively melodramatic music, the apparent addition

in certain instances of sound over silent footage creates the same

sort of queasiness occasioned by the unacknowledged dubbing of

Hitler, Eva Braun and others in the ‘home movie’ sections of

Swastika. (As a relief from such procedures, one feels especially

grateful for the two sequences in which the sounds of planes and/or

artillery are heard over a dark screen, thereby eliminating the

possibilities of distortion.) Otherwise, some fancy impressionistic

camera effects in the fictional parts — blurred slow-motion, a falling

soldier reflected in an eyeball — call attention more to themselves

than to their subject, while the memory and dream sequences near

the end are only marginally more effective. The depressing

conclusion forced on one by Overlord is that, in spite of the wealth of

material it has to work with and its evidently sincere aim to bear

witness to an area of history, the material merely becomes grist for

the illustration of some oft-told homilies, while the principal

‘reality’ that the film bears witness to is, inevitably, its own strategies.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

***

An interesting failure, this rarely seen 1975 English feature about World War II combines documentary and fictional elements, though they tend to undermine each other. Director Stuart Cooper culled a remarkable selection of newsreels from the Imperial War Museum and, collaborating with cowriter Christopher Hudson, integrated them into a sincere but cliched story about a young soldier (Brian Stirner). Shooting in black and white, the brilliant cinematographer John Alcott (Barry Lyndon) matches up the dramatic scenes with the archival footage, yet the filmmakers’ ingenuity often seems misplaced; in particular, added sound effects compromise the precious truth of the documentary materials. 83 min. (JR)