From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1976 (Vol. 43. No. 510). — J.R.

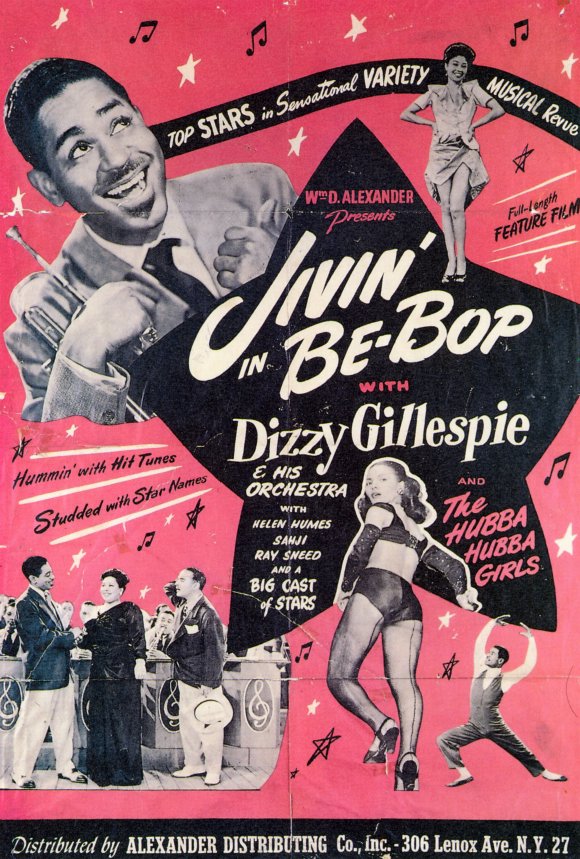

Jivin in Be-bop

U.S.A., 1947Director: Leonard Anderson

Dist—TCB. p.c—Alexander Productions. p—William D. Anderson. sc—Powell Lindsay. ph—Don Malkames. ed—Gladys Brothers. m/songs–(including) “Salt Peanuts”< “I Waited for You”, “Dizzy Atmosphere” by Dizzy Gillespie, “Bop-a-Lee-ba” by Dizzy Gillespie, John Brown, “Oop Bop Sh-‘Bam” by Gil Fuller, Dizzy Gillespie, Roberts, “Shaw ‘Nuff” by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, “A Night in Tunisia” by Dizzy Gillespie, Frank Paparelli, “One Bass Hit”, “Things to Come” by Dizzy Gillespie¸ Gil Fuller, “Ornithology” by Charlie Parker, Benny Harris,” “E Beeped When He ShouldaBopped” by Dizzy Gillespie, Gil Fuller, John Brown, “Crazy About a Man”, “Boogie in C”, “Boogie in D”, “Shoot Me a Little Dynamite Eight”, “Grosvenor Square”. sd—Nelson Minnerly. with—Dizzy Gillespie and his Orchestra, Sahji, Freddie Carter, Ralph Brown, Helen Humes, Ray Sneed. San Burley and Johnny Taylor, Phil and Audrey, Johnny and Henny, Daisy Richardson, Pancho and Dolores, Milt Jackson, John Lewis, Ray Brown, Kenny “Pancho” Hagood. 1,160 ft. 60 min. (16 mm.)

A continuous series of musical performances and dance routines shown on stage, without a visible audience, occasionally interspersed with comic repartee between Dizzy Gillespie and an emcee identified variously as “Peanut Head” Jackson and Burt.

Apparently designed as a second feature for cinemas catering exclusively to black audiences, Jivin in Be-bop has a fascination today as a period piece which often bypasses its purely musical interest. The latter aspect, to be sure, is far from negligible: Dizzy Gillespie’s big band in the Forties was a dynamic if occasionally undisciplined unit which played a substantial role in popularizing the discoveries of Charlie Parker, Bud Powell and Gillespie himself, retaining some of the intricate bebop lines that were used in smaller groups while broadening the music’s potential audience by adapting it for dancing and interlacing it with the leader’s comic shenanigans. Unfortunately, most of the versions of the band’s repertoire here are decidedly inferior to the recorded versions available elsewhere, and the obvious dubbing of the music places severe limits on any sustained illusion of spontaneity. On a showpiece like “Things to Come”, for instance, there is probably more surprise and excitement in the unexpected grin of an alto sax player during his neighbour’s solo than in the leader’s under-recorded trumpet. To make matters worse, most of the comic exchanges between the emcee and Gillespie are excruciatingly witless (“How long was Cain mad with his brother?” “As long as he was Abel”), and when the stage is taken over by a hackneyed piano-and-organ duo performing “Boogie in C” and “Boogie in D”, the musical interest virtually evaporates. The many dancers featured are equally variable: a fast shuffle by Johnny and Henny which eventually turns acrobatic, a woman dully shedding veils to the strains of “Shaw ‘Nuff”, a couple illustrating “A Night in Tunisia” in front of a neo-Egyptian décor, a bizarre female solo combining Hawaiian and American Indian elements, and a superb unidentified male dancer who performs beautifully to another up-tempo number by leaping nimbly amidst cardboard clouds. [2012 afterthought: this must be Ray Sneed, seen in the photos below.] (All the numbers are filmed in static set-ups while the band plays off-screen.) Other highlights include a Billy Ecksteinish performance of “I Waited for You” by Kenny Hagood — the singer on Miles Davis’ famous Birth of the Cool date while a woman gazes ethereally at him and the ceiling in turns, and a rendition of “Crazy About a Man” by Helen Humes that is full of gusto. Another sort of interest can be found in the appearances of the two major soloists of the Modern Jazz Quartet, which was formed some five years later, John Lewis and Milt Jackson. The former, looking studious and withdrawn, is not accorded any solo space to speak of; the latter solos quite a bit, but curiously enough becomes visible only in the latter portions of the film – with somewhat climactic effect, because Jackson is an extremely visual performer whose instrument (the vibraharp) can be played only by dancing. Gillespie’s trumpet is prominent throughout, and if none of his solos matches the fierce beauty of his playing on, say, “Manteca” (recorded the same year), he none the less sustains a flow of ideas and a purity of tone that reminds one that the Forties were truly his heyday.