Adapted from “Cannes, tour de Babel critique,” translated by Jean-Luc Mengus, in Trafic no. 23, automne 1997. –- J.R.

By common agreement, the fiftieth anniversary of the Cannes

Film Festival, prefigured as a cause for celebration, wound up serving

more often as an occasion for complaint. Disappointment in the over-

all quality of the films ran high, even if the arrival over the last four days

of films by Abbas Kiarostami, Atom Egoyan, Youssef Chahine, and

Wong Kar-wai improved the climate somewhat. But I don’t mean to

suggest that the shared feelings of anger and frustration demonstrated

any critical unanimity. On the contrary, the overall malaise of Cannes this

year forced to a state of crisis the general critical disagreement and lack

of communication that has turned up repeatedly, in a variety of forms.

If the pressing question after every screening at Cannes is whether a film

is good or bad (or, more often, given the climate of hyperbole,

wonderful or terrible) — a question that becomes much too pressing, because

it short-circuits the opportunity and even the desire to reflect on a film for

a day or week before reaching any final verdict about it — the widespread

disagreements at the festival derived not only from different and

irreconcilable definitions of “good” and “bad,” but also from different and

irreconcilable definitions of “film.” And the ensuing Tower of Babel

brought into sharp relief the competing agendas — in some cases

implicit, in come cases explicit — of such an occasion.

One film that I like, for instance, unlike most of my colleagues, is

Wim Wenders’s The End of Violence, yet the very terms of my

approval — that Wenders has finally succeeded in making an

entertaining Hollywood film — is so much at odds with the terms of

the other critics and programmers I speak with, who find the film

neither entertaining nor Hollywood, and who find it “heavy” to the same

degree that I find it “light,” that we might as well be speaking different

languages. Fifteen years ago, at the Toronto Film Festival, I experienced

a similar sense of isolation after seeing and liking Wenders’s Hammett.

My conclusion then was that Wenders had belatedly fulfilled one of the

central dreams of the French New Wave and its offspring (such as Bertolucci’s

project to adapt Red Harvest) — to make a European cinéphile feature

employing all the resources of a Hollywood studio. But in 1980, at least,

I still had the New Wave Hollywood as a reference point to employ.

Today the only terms I can draw upon to describe The End of Violence

are “Hollywood” and “art film,” and both terms, I discover, are no longer

categories that refer to shared realities to the same extent; more

precisely, they’re the ghosts of categories that continue to be used only

because others haven’t yet been found to replace them. So maybe one

reason why what I find light, entertaining, and thoughtful others find

heavy, boring, and preachy is that we’re calling on different contexts and

instruments of measurement. I’m thinking of all the recent stupid

American commercial films that bore and offend me, which makes The

End of Violence look good, but others are thinking of Wenders’s

previous nineties films, which they (and I, for that matter) regard as relatively

boring and forced, and see the film as part of the same negative pattern.

Even the usual way of identifying festival films, such as title, director,

and country of origin, is sometimes inadequate or misleading.

Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry, by all counts my favorite film at the

festival, regarded by most people as purely Iranian, makes prominent

use of Kurdish, Afghan, and Turkish characters, and ends with a recording

of “St. James Infirmary” by Louis Armstrong. When asked in his press

conference about why he used a “jazzy” trumpet at the end, Kiarostami

spoke of neither the relevant images of death contained in the lyrics of

“St. James Infirmary” nor of Armstrong, but of his conviction that music

belonged to everyone in the world, adding that the trumpet evoked the

soldiers in training that are seen in the final sequence. The fact that this

final sequence was shot in video was even more troubling to some

viewers than the jazz trumpet, but surely both the music and the video

constitute a kind of lingua franca within both Iran and the cinema as a

whole — suggesting that in an era when multicorporations may be more

pertinent as defining entities than countries, the usual definitions of

nationality have to be reformulated, reimagined, rethought. Like the

outworn categories of film criticism, much of the current nationalistic

discourse refers to the past, not to the present or the future. This isn’t to

say that certain references to the past don’t continue to be useful.

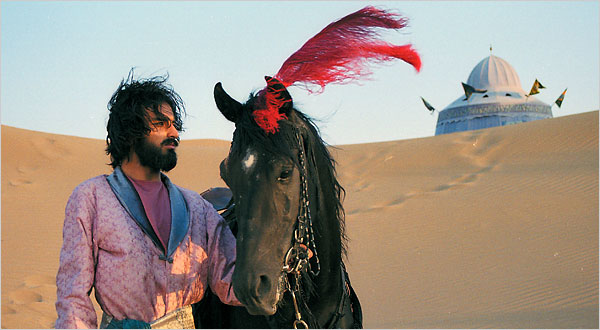

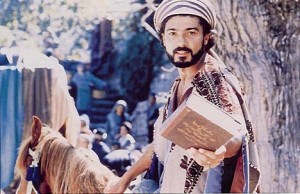

Yousef Chahine’s Destiny is a French-Egyptian grand spectacle and

musical that recounts the life of the Andalusian philosopher Averroes.

But I suspect that the most important reference point shared by

Chahine and myself is actually a style of Hollywood studio filmmaking

of the fifties, so that I’m reminded at various moments of films as good

as The Adventures of Hadji Baba and as mediocre as Kismet — a house

style that I associate mainly with M-G-M and only secondarily with

various directors (e.g., Anthony Mann, Richard Thorpe, Don Weis,

Vincente Minnelli, George Sidney, Mervyn LeRoy). By the same token,

even though Chahine, as evidenced by his retrospective in Locarno last

year, is fully recognizable as an auteur, this doesn’t necessarily mean

that the aspects of Destiny that are or should be most interesting to me

are its personal traits. I’m more inclined to be fascinated by the route of

a Westerner (myself) into the mysteries of Arabian and Egyptian cinema

charted over distant memories of Hollywood films made over forty years

ago, a process in which Chahine serves as one of many possible

emissaries rather than as any particular destination. But old critical reflexes

die hard, and a surprising number of films at Cannes encounter certain

kinds of critical resistance precisely because the auteurist grid of

director, camera, and mise en scène doesn’t yield the proper results.

One case in point is the charming and lively French Canadian

feature Cosmos shown in the Fortnight, a collection of slightly

interconnected comic sketches filmed in Quebec City in black-and-white by six

young writer-directors, one of them the cinematographer of the entire

feature. The narrative form in which two or several stories equals one

story — represented in twentieth-century literature by such works as

Faulkner’s The Wild Palms, Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, and Joyce’s

Dubliners — has many interesting examples in cinema ranging from

Intolerance to Out 1, from The Little Theater of Jean Renoir to

Kieslowski’s Red, and from Vera Chytilova’s About Something Else to Errol

Morris’s Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control. Though less significant than

these films, Cosmos still poses interesting methodological problems by

having multiple authorship as well as multiple stories. The

conventional critical approach to such a feature is to evaluate the style and

mise en scène of each episode separately, but to do that in this case is

nonfunctional because what these sketches have in common — a

certain New Wave flavor — is much more important than what

distinguishes them from one another. (This was also true of some of

the early New Wave features when they first appeared, before they became

recatalogued along auteurist lines.) Some of the episodes overlap via i

ntercutting, and clearly the feature as a whole was conceived and to some

extent executed collectively.

A related critical conundrum was posed by the 1995 U.S. release of

the 1964 Soviet documentary I Am Cuba — a film that is commonly

credited to its director (Mikhail Kalatozov) rather than to its

cinematographer (Sergei Urusevsky) or its cowriter (Yevgeny Yevtushenko)

when its eccentric style can’t really be read as the expression of a single

consciousness. When, in a famous early extended take, the camera on

a rooftop overlooking the Havana beaches moves several stories down to

tourists around a swimming pool, then follows one woman in a dress

only to abandon her in favor of a bathing beauty whom it then follows

into the swimming pool, even proceeding underwater with her, the

usual critical procedure is to identify Kalatozov with the camera and to

applaud his virtuoso mise en scène. But in fact, the shot was carried out

by a relay team of three separate camera operators — a good example of

collective work in action, communist filmmaking in the truest sense of

the word — and in the final analysis the model of a solitary artist

probably functions better here as a guide to reading the shot than as any

reliable indication of its mode of execution.

The problem, really, is that critics are still dealing with the residue

of a polemical position about mise en scène that was once necessary to

win certain battles, but which has regrettably eclipsed and obscured

other central creative areas — including even what the films are about.

Few critics took Orson Welles at his word when he insisted that he

always began with the written word, not with images, and indeed, the

writer-director-performer has perhaps suffered the most from the

critical emphasis on the latter two functions: how many critical studies have

bothered to consider the essential importance of Charlie Chaplin and

Erich von Stroheim as writers — inextricably tied to their work as actors,

which their mise en scène served largely to implement?

***

The most striking difference for me in overall atmosphere between

Cannes in the seventies and Cannes in the nineties can be seen in the

press conferences, which used to resemble gladiatorial combats and are

now almost completely predetermined publicity sessions, most of them

controlled by compulsive politeness and relatively useless when it comes

to the exchange of either ideas or information. Two characteristic

questions I can recall from the seventies are (1) after the screening of The

Mother and the Whore, addressed to Jean Eustache: “Why did you choose

to make a film instead of write a novel?” and (2) after the screening of One

Hamlet Less, addressed to Carmelo Bene, dressed in a white suit: “Do you

sleep at night in pajamas or in the nude?,” to which Bene replied, “Fuck

you.” Today, the most characteristic question is to ask a star what it was

like to work with a director (or vice versa), and no less characteristic are

the responses—testimonials about how wonderful he or she is.

What happened to alter this former climate of contestation, which

I find this year only at the press conference for Mathieu Kassovitz’s

Assassin(s)? The latter movie is as typical of current filmmaking trends

as the title of Michael Haneke’s Austrian film, Funny Games, the latter

functioning as both a commercial ruse and an ironic critique of a

commercial ruse — making Haneke’s film as divided against itself as

Assassin(s), a lowbrow exploration of the same general theme. Even

Kassovitz’s flagrant borrowings from Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and

GoodFellas and Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers testify to the same

puritanical duplicity that is found in these sources: the simultaneous

desire to succeed commercially in the American manner while

criticizing this very manner is a form of hypocrisy already found in the

Scorsese and Stone films.

The desire to see some old-style Cannes squabbling is what drove

me to Kassovitz’s press conference, though alas, despite his cogent

efforts to challenge the lack of seriousness of the press, not very much

light was shed at this event — except, perhaps, for the hostility of the

press at Cannes toward any film that has an overt thesis of any kind.

(1999 postscript: Another casualty of this bias was Johnny Depp’s

muddled and naive but touching The Brave, a first feature starring Depp and

featuring Marlon Brando in a cameo — an allegory that recalled sixties

follies such as Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie and was received so

poorly that, like Assassin(s), it has never opened in the United States.)

Clearly a lot has happened to information flow over the past twenty

years, at least within the public sector. First of all one should cite the

development of techniques designed to flatter and thereby control the

political press inaugurated in the United States by the Reagan

administration. Then came the adaptation of these same techniques by

Hollywood publicists, while at the same time the studios’ publicity

campaigns became more lavish, leading to the corrupt allegiances of

“entertainment news” in which publicists and journalists willingly join

forces against the interests of the public, leading to the mode of mutual

flattery that now predominates. Within the new system, any journalist

who asks a rude or skeptical or probing question risks losing access to

the publicists who control access to the “talent” (stars, directors,

writers, etc.) and alienating his or her own editor in the process.

The cosmetic surgery performed on news in these transactions

applies to nearly all the Cannes press conferences, not merely those for

expensive commercial films. Consider, for instance, the high drama

constructed around the alleged state banning of Kiarostami’s Taste of

Cherry because of its treatment of the theme of suicide. Certainly the

question of whether the Iranian government would allow the film to be

shown in Cannes was a genuine issue prior to the festival — not because

of its theme, as it turned out, but because of a bureaucratic technicality —

but the fact that this issue was settled before the festival began didn’t

stop Gilles Jacob from orchestrating its eventual arrival like a

breathless cliffhanger.

Furthermore, the self-righteousness of many critics and journalists in

denouncing state censorship — generally more relevant to the career of

Mohsen Makhmalbaf than to that of Kiarostami — doesn’t prevent them

from ignoring (and thus tolerating and helping to protect, therefore

supporting) the numerous instances of capitalist censorship, some of which

are perhaps even more damaging to the works in question. A key

example in this regard is Nick Cassavetes’s She’s So Lovely, derived from a 1980

script called She’s Delovely by John Cassavetes that, according to Thierry

Jousse, was rewritten in 1987 when Sean Penn was being considered for

the leading role. For me, the primary interest of this film is the unique

access it provides to the original script (presumably the 1987 version)

rather than the relative skill of its author’s son as a director — another case

where the issue of mise en scène becomes secondary (except, here, as a

relatively negative factor: what appears to be a Hollywood reading of an

independently conceived script). It is, after all, a kind of companion piece

to A Woman Under the Influence (1975), and the only (John) Cassavetes

project I’m aware of that combines the working-class milieu of the earlier

film with the middle-class suburban milieu of Faces — therefore a

contribution, however partial and modest, to the Cassavetes oeuvre.

But consider all the things that interfere with that contribution,

most of them separate instances of capitalist censorship. First of all the

title, She’s Delovely, which I’m told has been altered because of

the financial demands of the estate of Cole Porter, the composer of the

song of that title. (The song is still heard briefly in the first part of

the film, and the title still figures in a key line of dialogue spoken by

the central character, played by Penn, in the second part, a pure

example of irrational Cassavetes wordplay: “She doesn’t love you. She doesn’t

love me. She’s delovely.”) The confusing results are that the film itself

still bears the original title at its festival screening, but both the press

book and all the festival announcements call it She’s So Lovely, a more

awkward and less pretty title.

Secondly, there is a question of how far Nick Cassavetes has

honored the original script. When I ask him about this at the press

conference, he confesses that there were certain things in the script that

he didn’t understand (he fails to say what), and that he simply

eliminated those parts. (Properly speaking, this isn’t capitalist censorship,

though the fact that the script hasn’t been published — which would

allow us to check this matter for ourselves — remains a pertinent

issue.)

Thirdly and fourthly, I should mention two rumors I hear from

reasonably reliable sources about the film: (1) Penn directed the last third

of the shooting, when Nick Cassavetes became indisposed, and (2)

Harvey Weinstein, the codirector of Miramax (which helped to produce

and plans to distribute She’s So Lovely), substantially recut the film and

played an important role in overseeing the music before it was screened

at Cannes, making changes that were so pronounced that Nick

Cassavetes, I’m told, seriously considered removing his name from the

film. Needless to say, neither of these rumors is even slightly hinted at

in the press conference, where Weinstein is present along with the stars

and director; all one hears about there is everyone saying how

wonderful everyone else was to work with.

In short, at least four separate and successive kinds of interference

prevent She’s So Lovely from being unproblematically either “a film by

Nick Cassavetes” or “a film written by John Cassavetes,” although this

is precisely how it is represented at the press conference and in the

“preliminary press notes” distributed to journalists. So even the interesting

methodological challenge of coming to terms with a Hollywood version

of a John Cassavetes script — a version in which the more nonnaturalistic

and irrational elements figure either as flaws or as eccentric

cadenzas — becomes undermined by a process of disassociation and

subterfuge whereby “Cassavetes” figures less as a description of

contents than as a brand name. I’m reminded of George Hickenlooper

announcing several years ago his intention to film Welles’s script The

Big Brass Ring (which he has subsequently rewritten) because he was

“an auteurist at heart” — a declaration that made me wonder which

auteur he could have been thinking of.

Another form of capitalist censorship — this one usually less

conscious, and much more prevalent in the United States than in

Europe — is a refusal to discuss capitalism itself, predicated in part on

its omnipresence. (If capitalism is now the air we breathe, discussing it

is presumably as superfluous as discussing the air while describing a

particular landscape.) This is apparently why Neil Labute’s In the

Company of Men, in some ways the most provocative American film

I see in Cannes — shown in Un Certain Régard, and already written about

extensively in the states since its showing at Sundance — is almost never

described as a film about capitalism and its effects, and neither is The

Sweet Hereafter. The first describes the effects of aggressive

competition via business on notions of masculinity and romance, the

second evokes the effects of aggressive competition via litigation on the

functioning of a community, but neither is examined too closely by critics

as a commentary on the way we live. To deal with such a subject,

notions of nationality, mise en scène, and authorship may be useful in

taking us part of the way, but we have to travel the remaining distance

without such vehicles, on our own feet — if only because the pedestrian

can see things that drivers often miss, and can travel places accessible

only on foot. Considering how centrally vehicles figure in three of the

best films in Cannes, all of which revolve around mysteries of existence

and identity — cars in Taste of Cherry and Manoel de Oliveira’s Voyage

to the Beginning of the World, a school bus in The Sweet Hereafter — it’s

worth considering how far the vehicles of our critical categories

actually take us, and how far we might be able to travel if we learned how

to walk again. (Last year’s Goodbye South, Goodbye was also concerned

with vehicles, and the film ended memorably when the last of these ran

off the road and stopped.) The most beautiful shot I see in any film at

Cannes, composed like a Brueghel landscape, is the bus accident in

The Sweet Hereafter, seen from afar, and it’s clearly the view of a

pedestrian who stops to look, not one of a driver who speeds past.