Written circa June 2010 and previously unpublished. — J.R.

I can still recall the amusement of Penelope Houston — my boss, during the mid-1970s, when I was working for British Film Institute’s Editorial Department, on the staffs of Sight and Sound and Monthly Film Bulletin — whenever she came across routine references to directors Samuel Fuller and Douglas Sirk as “neglected” figures. Even though very few Anglo-American cinephiles could have even identified Fuller and Sirk during the 1950s, when most of their major films were coming out, Penelope certainly had a point when it came to questioning how “neglected” they still were among contemporary cinephiles in the U.K., especially after the Edinburgh film festival had extensive retrospectives devoted to each of them in 1969 and 1972, respectively. By the mid-70s, at least three books about Fuller and two about Sirk were available in the U.K — none of which appeared to have the slightest effect on their status as “neglected” filmmakers, according to the usual sound-bites.

Penelope indeed had a point. But then again, so did the various teachers and journalists who described Fuller and Sirk as “neglected,” because even though one book about each figure was published in the British Film Institute’s Cinema One series (a joint effort of the BFI’s Editorial and Education Departments in which Peter Wollen had a voice as well as Penelope), these directors remained relatively shadowy figures in Sight and Sound, a quarterly in that period which had a guaranteed subscription list based on BFI membership and therefore an unparalleled degree of clout over other film magazines in the U.K. So the term “neglected” in this instance had to be unpacked before one could even begin to evaluate it.

A similar paradox comes to mind nowadays whenever I hear about the “marginal” status of Pedro Costa. Granted, no film of his ever turned up at the New York Film Festival prior to Ne Change Rien, his black and white music documentary with Jeanne Balibar, in 2009, and the continuing lack of name recognition even among some reasonably knowledgeable cinephiles can’t be overlooked. Nevertheless, in April 2008, Michael Guillén reported on the Web that “Still Lives: The Films of Pedro Costa,” organized in Lisbon by Ricardo Matos Cabo (who subsequently published a substantial anthology in Portuguese to go with it, cem mil cigarros), “launched at Toronto’s Cinematheque Ontario,” had by then “traveled on to the Vancouver International Film Center, Manhattan’s Anthology Film Archives, the REDCAT in Los Angeles, the Harvard Film Archive, the Cleveland Museum of Art, Chicago’s Gene Siskel Film Center, Seattle’s Northwest Film Forum, Rochester’s George Eastman House, the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, and recently the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, California.” Among its many other venues, one could also cite (a small sampling) Australia’s Mercury Cinema (Adelaide), Queensland Art Gallery (Brisbane), and the Melbourne Cinematheque, South Korea’s Jeonju International Film Festival., London’s Tate Museum, and the Paris Cinémathèque.

None of this, of course, can be called the same thing as a “commercial release”. But I’m not sure it’s accurate, either, to speak about Criterion’s Letters from Fontainhas: Three Films by Pedro Costa, as a release that fills a gaping hole, exactly — even though it certainly qualifies as an epic undertaking, and it does offer considerably more than its title promises. This is a package including not only three recent Costa features (Ossos [Bones], No Quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room], and Juventude em marcha [Colossal Youth]), but also two of his more recent shorter films (Tarrafal and The Rabbit Hunters), and an interactive video installation piece (Little Boy Male, Little Girl Female) in which outtakes from In Vanda’s Room and Colossal Youth are juxtaposed side by side, as in Andy Warhol’s The Chelsea Girls (and, as Costa points out in a separate audio commentary, viewers are implicitly invited to furnish their own “editing” of these rushes) — along with a feature-length documentary and a shorter video essay by Jeff Wall about his work, and a 44-page booklet, among many other extras.

This also happens to be the fifth Costa DVD box set I’ve received to date, following ones from Portugal, Japan, Spain, and France, and not counting individual, single-disc releases from Portugal and the U.K. — and I doubt that this list is exhaustive, either. The broader point I’m trying to make is that what we mean by “neglected’ and “marginal” has never been more confused than it is today because so many of the relevant paradigms of filmgoing are in a serious state of flux. To put it crudely, DVDs and the Internet are rapidly recanonizing film culture as well as film history, and reconfiguring what we mean by marginal in a number of significant ways. The degree to which Robert Bresson went from being so seemingly esoteric that he was virtually a laughing-stock in the 60s, even among many serious Anglo-American cinephiles, to becoming almost universally revered within the same sphere at the time of his death, in 1999, is only one example of what I mean; the changing critical fortunes of Carl Dreyer and Andrei Tarkovsky within roughly the same time frame are two others.

Costa, even though the intensity of his work sometimes recalls that of Dreyer, Bresson, and Tarkovsky, is deemed “difficult” for somewhat different reasons — chiefly because his narratives are often uneventful by ordinary standards and because they’re often difficult to follow as narratives. Deciding how we choose to canonize him — which is virtually a prerequisite for whatever kinds of appreciation we can and should bring to his work — is a crucial matter, and one that’s complicated in some ways for an American audience by Costa’s idiosyncratic way of rethinking the art of Hollywood as well as the politics and morality of low-budget (or no-budget) independent filmmaking, which sometimes involves his rethinking the art of Andy Warhol’s filmmaking as well. Ever since he started to focus his attention in 1995 on a Lisbon ghetto called Fontainhas and some of its impoverished and mainly unemployed inhabitants, he has gradually forged a new way of working involving minimal crews and extended shooting schedules that allow for a good many rehearsals and retakes. As the Argentine film critic Quintín has described it, more generally, Costa is “quietly telling whoever will listen that cinema is exactly the opposite of what 99% of the film world thinks, and he is getting more radical every day.”

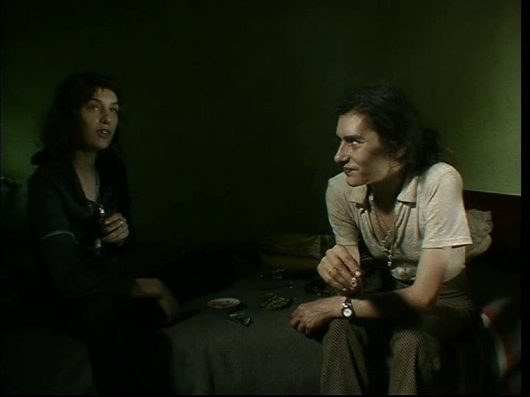

The casts of Ossos, In Vanda’s Room, and Colossal Youth — including, most memorably, a onetime crackhead (white) named Vanda Duarte and a defeated patriarch (black) named Ventura — and their cramped quarters are the camera’s principle subjects, rendered with an astonishing painterly beauty, but the sounds, which eventually include the razing of nearby buildings and the demolition of virtually the entire neighborhood, generally suggest a wider universe. By the end of Colossal Youth, both Vanda (now an ex-addict) and Ventura have had to move to more antiseptic high-rises elsewhere, but we’re not persuaded that this is necessarily an improvement in their lives. And the overall physical concentration on Fontainhas throughout the trilogy is such that the few times it leaves that area are major events. James Quandt has argued in Artforum that the most shocking single moment in Colossal Youth — indeed, the most shocking single instant he found in any film he saw at Cannes in 2006 — was a cut from a Fontainhas location to the Rubens painting painting Flight into Egypt hanging in Lisbon’s Museu Calouste Gulbenkian when Ventura, who once worked on the original construction of this museum, pays a brief visit there.

Costa first came into contact with Fontainhas after returning to Lisbon from the former Portuguese colony Cape Verde, where he had just shot his beautiful second feature, Casa de Lava (House of Lava) — a film already full of guilty self-questionings about the moral ambiguities of “going native,” when a Lisbon nurse (Inês de Medeiros) accompanies a Cape Verdean construction worker (Isaach de Bankolé) in a seemingly permanent coma back to his island home. “Without Casa de Lava,” Costa told Chicago journalist Patrick McGavin in a phone interview last March, published on McGavin’s web site Light Sensitive, “there’d be no other films. It was the film that gave me the direction. They gave me the addresses and they just told me they’d never see me again. They’d say, ‘Take this message to my mother. Take this package of tobacco to my father.’ They are all immigrants in this place. That’s how I found Fontainhas. You’d probably never go there. It’s almost a destiny, the key to the other films.”

The first feature Costa made in Fontainhas, Bones, was very much a transitional work. Inspired by a news story about a young woman from that quarter who tried to her sell her baby in a train station, it was his third and final feature to be made in 35 mm, with a conventional crew as well as a script, and a cast composed of both local nonprofessionals (including Vanda Duarte) and a few professionals (including de Medeiros, who’d already played in Costa’s two previous features, and Vanda Duarte’s sister Zita). But it was his frustration with all the trappings of industrial filmmaking, especially in these surroundings, that drove him to radically revise his filmmaking practice in his next films: taking over the cinematography himself and shooting digitally, drastically reducing his crew to three or four people, and rehearsing and reshooting far more than he ever could have afforded to do on his previous films.

Out of this new methodology have emerged two monumental and heroic epics, In Vanda’s Room (171 minutes) and Colossal Youth (156 minutes) — although it’s important to add the formal and stylistic differences between these two films are substantial. As critic Cyril Neyrat and philosopher and aesthetician Jacques Rancière point out in their audio commentary to selected scenes from Colossal Youth, the latter film creates a mythical, tragic space of low angles and spiritual recesses where the living and the dead seem to coexist and even interact, in contrast to the far more naturalistic surfaces and rhythms of the earlier epic, which was shot much more like a Warholian documentary. Indeed, the degree to which each successive Costa feature implicitly critiques its successor seems as much a constant in his work as it is in the work of Dreyer.

Both In Vanda’s Room and Colossal Youth confirm the evidence already offered in Casa de Lava and Bones that Costa is one of contemporary cinema’s greatest colorists. (For that matter, even his two black and white features — O sangue (The Blood), his first feature, and Ne change rien, his most recent one, and Where Lies Your Hidden Smile?, a color film about the editing of a black and white film — are so exquisitely lit and modulated that they essentially belong in the same company.) And the painterly aspects of the Fontainhas films in particular have provoked the charge from some quarters of Costa “aestheticizing poverty”. Because his approach might be said to fuse certain aspects of both James Agee’s writing and Walker Evans’ photography in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men — which Costa acknowledges as an important influence in his audio commentary to In Vanda’s Room — I think it’s worth quoting William T. Vollmann’s pungent appraisal of that book in Poor People as a response to that charge:

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is an elitist expression of egalitarian longings. The tragic tension between its goal and its means contributes substantially to its greatness. Its Communist sympathies, expressed, I am sad to say, in the midst of the Stalinist show trials, expose its naïveté without which that greatness would not exist; for despite its fierce intellectualism it is essentially an outcry of childlike love, the love which impels a child to embrace a stranger’s legs. What can the stranger do, but smilingly stroke the child’s head? Few of its subjects could have read, let alone written it. James Agee sought to know them, to experience, however modestly, what they did; his heart went out to them, and he fought with all his crafty, hopelessly unrequitable passion to make our hearts do the same. This explains the necessity for Walker Evans’s accompanying photographs, which record the poverty of those sharecropper families calmly, undeniably, heartbreakingly, inescapably. Their project falls repeatedly on its sword. It is a success because it fails. It fails because it consists of two rich men observing the lives of the poor. The stranger’s legs may be approachable, but the stranger himself in his immensity stands too tall and far off in poverty to be ascertained in the easy way that our observers can see each other. Had this easiness existed in the portrayal of the book’s subject, it would have been patronizing. Accordingly, Agee carries his sincerity to the point of self-loathing, and Evans escapes into the tell-all taciturnity of photography. A picture is worth a thousand words, no doubt, but which thousand? Is your caption the same as mine? A poor man stares out at you from a page. You will never meet him. Is he grim, threatening, sad, repulsive, determined, worn down, unbowed, proud, all of the above? What can you truly come to know about him from his face? As for the photographer, he need not commit himself.

Agee does commit himself. He wants us to feel and smell everything that his subjects have to, and comes as close to accomplishing this as it is possible to do using the sole means of an alphabet; so he fails, despising himself and us that it must be so, apologizing to the families in an abstruse gorgeousness of abasement that only the rich will have time to understand — and of these, how many possess the desire? For to read Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is to be slapped in the face. (1)

There’s a certain paradox, to be sure, in suggesting that In Vanda’s Room and Colossal Youth fuse the dialectical oppositions of Agee and Evans into a single ambiguous practice. But I think it’s a conundrum well worth considering, because for me “an abstruse gorgeousness of abasement” describes rather well the ongoing contradiction that Costa is constantly grappling with.

***

Another complicating factor about the issue of critical neglect regarding Costa is that no one classifies him as a film critic, and yet his own critical intelligence concerning cinema as a whole — which involve radical configurations of the usual distinctions made between documentary and fiction, and between “experimental” filmmaking and Hollywood — is arguably a central facet of his work and its meaning. As with the otherwise radically different work of Lars von Trier — a cynical stepson of Rainer Werner Fassbinder in much the same way that Costa might be considered an idealist stepson of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet — one has to contend with the manner in which American culture has been redefined from afar through a European perspective. For von Trier, who has never set foot in the U.S., American culture remains a frequent reference point in terms of his own settings and other cultural references (such as the songs in Dancer in the Dark). But for Costa, the operative reference point is classic Hollywood as viewed largely from the perspective of Cahiers du Cinéma — a development of the perspective that generated such pictures by former Cahiers critics as Paris Belongs to Us, Shoot the Piano Player, Band of Outsiders, Alphaville, The Bride Wore Black, and Celine and Go Boating — and one updated by the “MacMahonist” offshoot of the Cahiers orthodoxy that eventually started its own magazine, Présence du Cinéma, represented by such figures as Jacques Lourcelles, Michel Mourlet, Pierre Rissient, and Bertrand Tavernier, and by a few others, e.g., the late Jean-Claude Biette and Louis Skorecki, two of Serge Daney’s comrades-in-arms, and the dissident Cahiers critic Luc Moullet. This latter taste leaned towards such alternative (or at least further valorized) Hollywood role models as Cecil B. De Mille, John Ford (not originally a member of the Cahiers pantheon, at least to the degree that Hawks, Hitchcock, and Nicholas Ray were), Samuel Fuller, Otto Preminger, Jacques Tourneur, King Vidor, and Raoul Walsh.

Above all, in Costa’s case, one has to appreciate the degree to which the results of his encounters with Fontainhas are movies, with all the grandeur and giddy excitement that this term implies, and not simply rarified arthouse objects. (This is perhaps also the point at which his documentary impulses are ultimately informed by Warhol as much as by such pioneers as Robert Flaherty.) And the same sort of paradox can be found in the critical thinking of his mentors, Jean-Marie Straub and the late Danièle Huillet — a filmmaking couple whose editing of one of their features is the focus of Costa’s fifth feature, Où gît votre sourire enfoui? (Where Lies Your Hidden Smile?, 2001), shot near the end of the protracted shoot that yielded In Vanda’s Room — the last and possibly the very best of a series of films about filmmakers produced for French television by André S. Labarthe and Janine Bazin (the widow of André Bazin) over nearly four decades. (Ironically, this is the most accessible of all of Costa’s features; yet it’s also the hardest one to find online, even though it exists with English subtitles, because it was brought out by a Portuguese book publisher with an accompanying book that’s only in Portuguese.) Although Straub and Huillet’s editing of one of the versions of their 1999 black and white feature Sicily! was actually being observed at the time by students as well as by Costa’s camera, Costa elides all the visible evidence of these students — a good example of his tendency to “fictionalize” documentary material (as well as to imbue his fictions with many of the characteristics of documentary) — in order to focus directly on the editing screen and show us how precisely what difference a single frame can make (a question raised by Costa’s mysterious title), or else on a broader view of Huillet handling the film and equipment physically while Straub either kibitzes or delivers various monologues while pacing in and out of the small room, which tells us something about their own relationship as well as about many of the political and aesthetic issues arising from their work.

The best single text displaying Costa’s critical gifts is a transcript of a series of remarkable lectures he gave in Tokyo in 2004 entitled “A Closed Door That Leaves Us Guessing,” published in the 10th issue of the online journal Rouge and including detailed and highly original remarks about Bresson, Chaplin, Dreyer, Ford, Lubitsch, the Lumière brothers, Mizoguchi, Ozu, Straub-Huillet, and Jacques Tourneur. This text isn’t reproduced in any of the Costa box sets, but since it’s available online (at www.rouge.com.au/10/costa_seminar.html) — as is Tag Gallagher’s essay about Costa “Straub Anti-Straub” (available online at www.archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/07/43/costa-straub-huillet.html) — this is hardly necessary, as long as one knows to access them. One can also find a related Straubian orientation in the elaborate, extended collage of texts and stills by American blogger Andy Rector entitled “Mutual Films” that’s included in the Spanish and French box sets, but only in those languages and not online.

The dialectic (or shotgun marriage) suggested by combining the materialism (as well as the idealism) of Straub-Huillet with the more disembodied and spiritual or supernatural realm of Tourneur — the director of Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, The Leopard Man, Out of the Past, Stars in My Crown, Wichita, Nightfall, and Night of the Demon, among other key works — is fundamental to Costa’s own aesthetic, and part of what distinguishes him the most from Straub-Huillet (who at one time or another have praised all the filmmakers discussed by Costa in Rouge, apart from Tourneur.) It also helps to explain why Casa de Lava, Costa’s avowed “remake” of Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie — my own favorite of his features, along with Où gît votre sourire enfoui? — may be the work of his that’s furthest removed from the austerity of Straub-Huillet, even though it opens with shots of their beloved Mount Etna and is as much of an epic landscape work as their own From the Cloud to the Resistance, Too Early, Too Late, The Death of Empedocles, and Workers, Peasants.

Lamentably, there’s no real equivalent to the critical touchstones of Costa, Gallagher, Rector, and Straub-Huillet themselves (in their interviews and in their dialogue in Costa’s documentary) found in the 44-page booklet included in the Criterion set. The criticism included here — by Cyril Neyrat (who’s also joined by philosopher and aesthetician Jacques Rancière in an audio commentary delivered in English to selected scenes from Colossal Youth), Ricardo Matos Cabo, Luc Sante, Thom Andersen, Mark Peranson, and Bernard Eisenschitz — is certainly sophisticated and perceptive. But it’s exclusively criticism about Costa’s work rather than about the critical tradition that this work relates to, springs from, and ultimately belongs with, which his Rouge piece illuminates so cogently. Notwithstanding that the first and last of these names, Neyrat and Eisenschitz, have both been editors of Cahiers du Cinéma (albeit in separate eras) and both clearly reflect that tradition, it’s a pity that there isn’t a little more here to spell out some of the rudiments of that tradition for the more landlocked American viewers, apart from, say, the fleeting cross-referenced comparisons of Ventura to Sergeant Rutledge and Judge Priest, two of John Ford’s heroes, made respectively by Andersen and Peranson. Admittedly, Straub-Huillet are mentioned or evoked repeatedly in most of the half-dozen essays, but one wishes there were more of a context here to place them critically as well. What’s basically missing from Criterion’s critical casebook, in short, is Costa’s cinephilia, which is only allowed to make guest star appearances in this massive package.

The main compensation for this absence is a lot of material that can’t be found elsewhere, including a series of illuminating dialogues between Costa and filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin — video conversations about Bones and Colossal Youth and an audio commentary to In Vanda’s Room, all in English. Gorin’s relaxed and friendly rapport with Costa makes him an ideal interlocutor for the more anecdotal side of Costa’s complex encounter with Fontainhas. (Less interesting, at least to me, is Auriélien Gerbault’s boiler-plate 2006 feature-length documentary All Blossoms Again, partly made during the production of Colossal Youth, and routinely included with most of the Costa box sets.) The down side of this is the way that, in spite of what seems like a great deal of editing, Costa’s spoken commentaries about his work, which often ramble, can’t match the printed verbal texts (including his own on Rouge) in terms of precision, especially when it comes to their relevance to what’s on-screen during the lengthy audio commentary. His sensitivity and his sense of poetry are never in doubt, but there’s a looseness in much of his speech, despite the fact that he’s often giving useful information — such as the importance of Creole in the Fontainhas dialogue, which explains why his films have to be subtitled in Portugal as well as everywhere else. In this respect, anyone watching In Vanda’s Room with this audio commentary needs to perform his or her own selective editing — the same thing Costa proposes that we do visually with the Little Boy Male, Little Girl Female rushes.

1.William T. Vollmann, Poor People, New York: HarperCollins, 2007, xii-xiii. Ironically, it was Costa himself who alerted me to the existence and interest of this book, albeit without suggesting in any direct way that it spoke for him or about him.