Written in mid-July 2011 as my 22nd bimonthly column (“El movimiento”) for Cahiers du cinéma España, which might be described as a Spanish extension (rather than the Spanish “edition”) of Cahiers du cinéma. A Spanish translation of this appeared in their September issue, no. 48. — J.R.

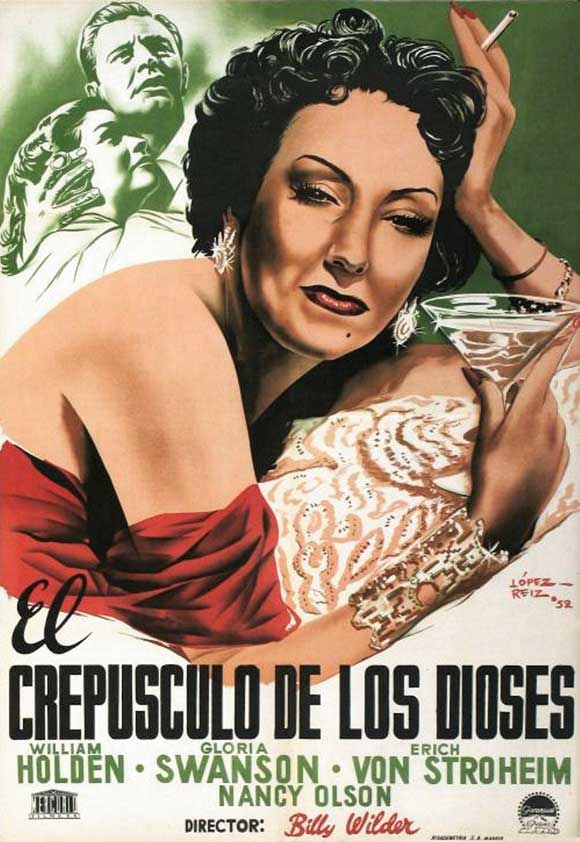

We all have different biases and thresholds when it comes to formulating our separate perceptions of history. Recently reading J. Hoberman’s new book, An Army of Phantoms: American Movies and the Making of the Cold War, which I mainly find an apt ideological reading of Hollywood in the early 1950s, I experienced a rude shock when I read his interpretations of two 1950 features, William Wellman’s The Next Voice You Hear (a very strange suburban family drama about God addressing the world over the radio) and Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. In both cases these interpretations were predicated on the assumption that both the Hollywood studios of 1950 and their audiences were preoccupied with television: “The Next Voice You Hear is of 1950 but not in it: the Smiths [the film’s archetypal central family] do not own a television set because, like God, TV cannot be shown on the screen.” And Sunset Boulevard “displaces Hollywood’s current crisis [i.e., the coming of television] to the technological crisis of twenty years earlier — the coming of sound.”

Hoberman is five years younger than me, so he was only two years old when these films came out, and he first saw The Next Voice You Hear in 1970, on television. I saw it with my family at New York’s Radio City Music Hall the summer it was released, and I’m sure that we weren’t thinking even slightly about television at the time. In 1950, radio and the movies were the only relevant media, both expected to last forever; at most, television might have been in the back of the minds of a few studio heads and a few families who purchased the first television sets. But it seems that people who grew up with television find it harder to imagine such a pre-television culture.

Similarly, I find myself gaping in disbelief at Michel Hazanavicius’s L’artiste when I see it at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, as a plausible depiction of the end of the silent cinema in Hollywood — a vision that looks almost entirely bogus to me, stylistically and in terms of period details. Yet I’m startled to discover that some specialists of silent cinema — including Kevin Brownlow, who’s five years older than me, and is present at the same screening in Bologna — find L’artiste both acceptable and moving. This seems to invalidate my theory about generational differences accounting for such divisions regarding taste. And in fact, Hoberman himself, even though he likes the film better than I do, seemed to agree with me when he reviewed the film from Cannes: “As a formal stunt, this (mostly) silent film love letter…adapts some basic tenets of pre-talkie visual storytelling to suit a modern gaze. But since there’s little here other than form…that process of adaptation feels like a cheat. If you’re making a silent film just to make a silent film, why employ a performance style that mimics not silent film acting nor naturalistic behavior, but the mid-century mugging of musicals like Singin’ in the Rain (The Artist‘s most obvious influence)?”

Indeed, how can one take seriously a film that contrives to express the sadness of the end of silent cinema in 1929 by using Bernard Herrmann’s music for Hitchcock’s Vertigo, a film made almost 30 years later, on the soundtrack? For me the employment of this music was a deal-breaker, making it impossible for me to take the film seriously. Sixteen years ago, in Martin Scorsese’s Casino, I had a similar problem adjusting to the use of Georges Delarue’s theme music from Godard’s Le mépris [Contempt] in order to express a character’s feeling of estrangement from his wife, which for me became a kind of rented expressiveness rather than any sort of emotional investment or discovery. But if we can ignore or overlook such sources, perhaps they no longer matter.