This is a story, never before published, written during my teens — most likely in early 1960, when I was a junior at a boarding school on a farm in Vermont, age 17. I’ve done some light editing. The illustrations, which I realize are not always consistent with one another or precisely congruent with the story, are all gleaned from the Internet.

This story is the second in a series of three to be posted, all fantasies and all written when I was in high school. (The other two stories can be accessed here and here.) I feel today that they were written by someone else, but it’s clear that all three of them are interconnected, including in certain ways that I might not have been fully aware of at the time. I like them in spite of their obvious flaws, and hope that visitors to this site will at least find them intriguing. — J.R.

Don’t Look Back

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

/Hey Jim you got that fire going yet? Good…kick that log in; that’ll help it,,,nothing like a good campfire once it’s really going, Say Joe are the Barneses here yet? Well -– we can start without them I guess –-

I guess you’re all wondering why I called you all together here tonight. I know we don’t like to meet often -– the young ones always ask questions -– but what I have to tell you is something important to us all. In order to tell you this I’ll have to go back a bit into my past; back I guess to when I was still a kid –/

When I first joined the Group I was pretty much of a young and uninformed kid. I was…let’s see, I think it was seventeen I was…Yes, that’s right.

Almost all I’d ever done up to that point in my life was help Dad with the farm. Of course I’d never gone to school –- our village has always been too far away from the rest of the world for it to make any difference –- but Mom and Dead taught me how to read and write. They could spend a lot of their time teaching me, since I was their only child.

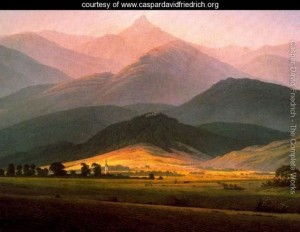

I didn’t know what I wanted then. Late afternoons I used to sit under an old oak tree in front of our cottage and look at the faroff mountains that went all the way around the horizon and think, What is life for, anyway? What lies beyond those mountains, and will I ever go there? Dad used to look at me sitting against that tree with knowing eyes. I guess he knew then and there that I wouldn’t be satisfied with just spending all of my life in the village.

Dad was a tall man with a lean and kindly face. As far back as I can remember he always had this thin wiry hair that was always growing too long and spilling over into his eyes, as if to shield them from the sun. He was a pretty strong man, but he didn’t have the kind of strength that would make him fight or move mountains – just the kind that enabled him to build a farm that was large enough for his small family to live on and then stop. He’d come from somewhere beyond the mountains before he met my mother and married her in the village, but he never would speak to me of his early life away from the cottage and farm. He never liked to talk about what lay outside of the village although I repeatedly asked him questions.

(– Whatsa matter boy, don’t you know yet what you want out of life?

— How can I Dad when I don’t know about anything except for what’s in this village —

— It’s better this way, Mark. Believe me I know. If you can’t find happiness here in the village, you won’t find it off behind that mountain or that one neither –-

— But what’s out there, what’s out there behind all those mountains?

— Nothing; not a thing that’d ever do you any good.)

My mother was the same way about it. Look Mark, she’d always say, I can understand but look this is just a phase you’re going through. I’m sure you’ll get over it –-

But I didn’t. I kept up with questions, even though they never did any good. I also tried some of the people in the village, but they would only tell me that they did not know.

Finally, one night, part of the truth came. It was in a dream I had of an enormous roaring waterfall.

It was a dream without action – just a vision of a waterfall, howling like the voices of a thousand dead souls…or maybe it was just a single shriek. I still don’t know. It made everything else I’d ever known seem like nothing. Around the waterfall were countless trees, caves and streams, all making up a gigantic forest that kept out the sky and held within itself more dark corners and secret shadows than I’d ever imagined existed. Everything seemed to be still, in awe of something –- perhaps it was the waterfall. The scene both fascinated me and filled me with fear –-

I woke in the quiet morning to the bright sun shining through the open window and tried to remember the dream. But I could only see it now as a distant glaze of misty colors, a faint awareness of something overwhelming. I pondered over it the next day, but on the following night I dreamt nothing. Then, a week later, the same dream came to me, and in the morning I had a clear picture of it in my mind.

It was in the autumn then, with the leaves beginning to fall like golden coins and rest on the floors of shaded thickets like matted quilts. My father and I spent the day harvesting wheat under the ripening sun.

Late in the afternoon I turned to Dad, and told him of my dream. As I told him, his face lit up with a deep smile.

(– It’s good that you’ve finally had the dream, he said. It’s a sign that you’ve grown up.

— What do you mean Dad?

— That dream is one that every adult in the village has several times a week, including your mother and I. We rarely speak of it to one another because it’s something that we hold to be very sacred, and talking of it might destroy its magic. But it’s a sign Mark…a sign of maturity, that you’ve grown up.

— What does the dream mean?

At first my question was answered only with stern eyes. — We don’t like to talk about that, Mark. Whatever its meaning, the dream is far too much for us to ever comprehend or understand. trying to find a meaning will destroy its beauty. No; don’t think of it that way — you can’t. The dream is meant for appreciation, not analysis –)

That night, when I couldn’t sleep, I knew that I would have to leave the village. It was not just this incident — there were many times my parents had left the cottage for several hours, always late at night when they’d thought I was asleep. When I would ask them the next morning where they had gone, they would say reluctantly, To the edge of the village. The graveyard. Why? I would ask. To go to a meeting, they would say, a meeting about grownup matters. And then they would say no more.

And there were other things: Words between them at meals, when there would be slips that they would try to cover up. I never understood the slips and always forgot them.

In the darkness I packed some clothes and a loaf of bread swiped from the kitchen, and in the yawning hours of the still night crept out of the cottage and onto the path that led away from the village. The night was ablaze with a bright moon and millions of stars that all seemed to be looking down on me. I gazed ahead at the distant mountains.

(– What’s it like out there? I thought as I walked, pondering over a faint glow of light that came from behind a mountain miles ahead. Are there more villages behind that mountain, or is it God? Will I ever find the waterfall?) I passed the dark cottages in silence, nearing the edge of the village.

Presently I approached the graveyard. I’d only been there once before, when I was very small, at the funeral of my mother’s aged father. I stopped to look for a moment at at the milky white tombstones, sitting like pale expectant faces in an audience. I knelt before the grave of my grandfather, and read his epitaph, which seemed to glow luminously by the light of the moon: ANDREW WILLIAM LEE HE KNEW THE WATERFALL IN HIS LIFE, AND NOW PERHAPS HE IS THERE.

What did it mean? Why was it that I’d never known of this epitaph before? I tried to remember my grandfather when he was alive, but could only piece together a few vague and isolated impressions.

After a while I stood up and quietly left the graveyard. The neat row of tombstones lay on the top of a hill that on one side gently flowed down into the village. I looked down at the dark phantom cottages and thought, this can never be my home.

The graveyard was surrounded on the three other sides by towering black trees, bared by autumn to resemble flayed hands, springing up from the ground and reaching for the sky. They looked cold and unfriendly, and I was anxious to leave —

But where to? The path spread far off down the other side of the hill and into the distance towards the mountains, pointing the way with a sure arm. But where did it lead to? A city perhaps, with the path flowing down every street and through every alley and into every room? As I felt a soft wind caress my neck, I started down the unsteep path. I soon passed a small campfire site, probably the one used by the adults of the village at their meetings.

After reaching the bottom of the hill I continued down the path for miles, passing not one cottage or any sign of people. The mountain ahead seemed as distant as ever.

Finally I saw something, a tiny yellow glow of light about half a mile ahead in a small thicket. I rushed towards the light, and soon heard a soft murmur of voices and saw smoke.

At last I was there. It was a huge fire, with dozens of people sitting on the ground nearby, singing a strange song with a guitar. I stood at the thicket’s edge for a moment, unseen by the others, and listened. The group was composed of all ages; there was an elderly couple, one middle-aged, two couples that seemed to be in their late twenties, and three of about my age — two girls and a boy. They were all concentrated on this peculiar song they were singing, and they had a faroff look in their eyes that frightened me. I listened to their song, sung with an eerie melody that I’ve never forgotten —

(– Sweet Betsy Ruth she married John,/but poor John did not know/that Betsy was a devil girl/and came from down below, oh, /Don’t look back behind you/or you’ll see the honest truth;/don’t look back behind you/or you might see Betsy Ruth.

/When they were walking home that night,/sweet Betsy in the rear, John heard her shout, he turned about,/and saw her then real clear, oh,

/Don’t look back behind youor you’ll see the honest truth;/don’t look back behind you or you might see Betsy Ruth.

/John turned around and saw her face/and then he knew the truth,/he knew that death was close at hand/ from the look of Betsy Ruth./He saw the gleam in Betsy’s eye,/the dagger in her hand;/she thrust the knife into his heart/and left him in the sand, oh, /Don’t look back behind you/or you’ll see the honest truth;/don’t look back behind you/or you might see Betsy Ruth….) The song was over, the group now quiet. I was terrified by their song, but I had to know who they were. I stepped into the clearing and showed myself. They all turned and looked at me with cold staring eyes, and for a moment I was afraid to speak. But then I told them my name, and asked who they were. (– Well Mark, I’ll tell you, the oldest man of the group said kindly. We don’t like to label ourselves much. We usually call ourselves the Group, Our aim in life is, well, I guess it would seem kind of ridiculous to you…you might call us searchers — we’re searching for a waterfall that we’re sure exists somewhere in the world. We’ve been traveling for generations and have received no real clues yet. But every day we hope –) It was that same night that I became a member of the Group. I told them all my story, and they readily accepted me. They were a nice bunch of people. The two oldest ones — we called them Dirk and Mary — were more or less the leaders, but otherwise there was no relative rank of anyone on the Group. The three youngest ones — Ann, Sue and Roger — were naturally the ones that I felt the most akin to. I spent most of the night talking with Roger near the fire while the others were asleep; in whispers I told him of my past life and he told me of his, although in his case he hesitated pretty much and I learned very little. Except for the married couples, none of the members of the Group were related, although they all felt very close to one another. Roger, Sue and Ann had also run away from home and had met up with the Group by chance as I did. (– Roger, as we lay under blankets mear the dwindling fire and dawn was nearing, What is it that’s known about the waterfall? — Not very much. We just know that it has to be somewhere, and wherever it is we want to find it. — Why? I asked. The word sounded strange and unsure in the air, and Roger looked at me for a moment with actual shock, but I had to say it. — I want to find the waterfall as much as you do, I said, it’s just that I don’t know why — — It’s very simple….The waterfall has the answers to the secrets, all of them. If it comes in a dream it must mean something…we know the waterfall must have something that will show us the answers — — The answers to what? — To what we are — once we know what we are we are only a step away from learning why. A definition of a hammer shows its use. And don’t you see, once we know that we know everything. It’s the ultimate goal of mankind, and yet the world ignores this like a pack of dumb animals –) I nodded in agreement, but said nothing. I was too tired to talk or even think, so instead I slept for a few hours and dreamed again of the waterfall…. We ate early the next morning, and made an early start at climbing a nearby mountain. It was a long and hard climb, almost vertical in places, but I didn’t have much trouble keeping up with the rest.

We reached the top near dusk, and saw at a brief distance a tall steel tower looming over the trees — although I didn’t know what one was then, because I’d never seen one before. Roger patiently explained to me that it was for locating forest fires in the area and reporting the immediately. (– Well that’s odd, I said. We’ve had fires in the village before, and we’ve never had any outside help –) I looked at the rolling land that spread off into the distance and tried to spot the village, but couldn’t. I told Roger. (– Don’t think about it, Mark. The village you came from is a thing of the past; you’ll have to forget it. Remembering things never does anyone a bit of good, and as often as not it does them a lot of harm — that’s one of the things the Group believes in, and it would be best if you believed it too. Just keep it in mind; it always hurts you when you look back.) I realized then why Roger had been reluctant to talk about his past the night before. Why is this part of the Group as well? I thought, wondering if I could ever fully become one of them. While the others pitched camp, Sue, Ann, Roger and I decided to walk over to the tower. It was only half a mile away.When we got to it, we noticed an elderly white-haired man standing nearby who greatly resembled my father. He looked amiable in his plain shirt, denims, and red cap. (– Howdy, he said. — On a camping trip? I’m the guy who works up in the tower….Say, haven’t I seen some of you up here before? You look mighty familiar — Roger hesitated. — No sir, uh, we’ve never been here before. I’m sure you’re mistaken. — But I coulda sworn. People look alike I guess. Where you kids from? — Oh, around, I said. Then Ann said: — Say, this must be a lonely job up here. You been here long? — Oh…bout five years, I guess. It’s a great job — nobody up here to boss you but yourself.)

Soon afterwards, the four of us climbed up in the tower with the old man and viewed the flowing expanse of land. Before we left, we invited the old man to come down to our fire and have some coffee with us. He said he would try to make it later.

When we got back to the rest of the Group, supper was cooking on the fire and we soon had a good meal. Afterwards Roger got his guitar out and we started the singing. It didn’t take me too long to catch on to most of the songs, and I was soon in the spirit of things.

A while later the old man from the tower came over. We gave him the promised coffee and he started in to talking with Dirk and some of the others.

( –Have you much interest in the location of the waterfall? Mary asked.

— The waterfall? I guess so. You know, it’s funny, but sometimes when I’m up in the tower, looking out over the land, I think I see a little sparkle that might be the waterfall. Maybe it’s my imagination, but I always notice this little thing way off in the distance, in the valley. Who knows?

Dirk suddenly became excited. — You really think so? he said. If so, could we have a look up in your tower tomorrow morning, just to make sure? It might be worth a chance —

— Yeah, sure. But mister, if you don’t mind, is it okay if I say something about it first?

— Of course,

— Well mister, I respect your group a lot, because I think its intentions are wonderful. But look…I mean, do you really expect to find this waterfall? You really think you can?

— Why not? Dirk said. It has to be somewhere —

— Sure. But listen: A few months ago, I was walking around this mountain top when I came upon this beautiful view of the valley, and there was a huge rock there where you could sit and view it all. Well let me tell you, that view overwhelmed me. I thought, this is the valley of the world. That’s what I thought. And then a week ago I was walking near the same place, completely forgetful of being there before, when I tripped and just about bashed my head in against that rock. Here I was in the same place and all I got this time was a bump on my head. Do you see what I mean, mister? How do you know that you’ll recognize the waterfall when you see it? What makes you think you will?

Dirk remained silent for a long time. Then he said, — I think I can agree with you to a certain extent. Your point’s well taken, to be sure. But that still gives me no reason to give our search up, it only shows us how hard it will be. We’d still like to have a look in your tower tomorrow.

— Oh, sure. But if I were you, I wouldn’t be chasing after any sparkles. I’d stop somewhere, build a house, wait ten years, and then look in my front yard. You’d have just as much chance finding the waterfall that way, maybe more –)

The old man left soon, and we resumed our singing for awhile. I didn’t feel much like singing, though, so I got up and walked away from the fire to think.

I walked a few yards out of the clearing, and then stopped to look at the stars. But soon I heard a voice come from nearby —

(– Do you think you’re happy in the Group? it said. I turned, and saw the voice came from a dark shadow that stood a few yards away. It was Ann, and she’d no doubt already been there — I hadn’t noticed her at the singing.

— I don’t know, really, I said. It’s hard to tell yet. I’m not so sure what the Group is yet.

— Sometimes I really don’t want to know. Ann stepped out of the shadows and into the moonlight, and suddenly she seemed very beautiful with the moonlight on her blond hair.

— Why do you say that?

— Oh, I don’t know. I don’t know much more than you do. I’ve been in the Group a year or so, and still know so little. But there’s one thing that really bothers me. …Remember at the tower today, that old man saying we looked familiar? Well the funny part of it is he looked familiar. I know I’ve seen him before — and I know that this isn’t the first time the Group has been here. I’m sure we were here less than eight months ago. But I’m afraid to say anything; you know what the others say about looking back. But I can’t help it, Mark. Sometimes I want to remember, I want to remember all sorts of things like what my mother and father looked like, what I was like when I was little, where I came from, what my house looked like…all those things, Mark, but they’re all like silhouettes to me now, I can only remember them like shadows. It makes me want to cry sometimes, but I never say anything about it to the others because I know they won’t understand. I’ve talked with Sue and Roger, but they won’t listen. All they do is say, memories hurt you —

— Yes, I said. It’s bothered me a lot too –)

Ann and I talked on into the night, telling each other all we knew about ourselves. Finally, as it grew late, we heard Dirk calling both of us. (– You better come get some shuteye, he said. We got a long day ahead of us, especially if we see something up in that tower.)

We called back we’d get some sleep before long, and then continued to talk. Finally there was a silence between us, and you could hear the whispering whine of the wind through the trees. Without a word, I stepped up to Ann and kissed her. He didn’t pull away, and I held her for a while, and we both knew that we wouldn’t feel like lost souls any longer in the Group. Now we both had someone to talk to away from the Group, someone who would understand.

After a while we walked on back to the fire, and parted into our separate groups.

I lay by the fire under the warm blankets, lingering for a long time over the moon that shone directly above me. After a while I slept and dreamed; only tonight the dream of the waterfall was different. This time the waterfall was more quiet and distant, like soft and faroff applause, and I was standing nearby with Ann, my arm around her waist, and we were both deliriously happy hearing the mighty roar and feeling the pulse of the waterfall….

I awoke near dawn, and saw Roger sitting up, staring intently at the ashes of the dead fire.

(– Roger, I said. I had the dream again, only this time it was different…Ann was in it this time.

Roger gave an impish grin and said, — That’s good. But why are you so surprised? Don’t you know that’s part of being in love? I guess no one ever told you — I’ve had the same type of dream about Sue before. And you know what, Mark? She was dreaming the very same dream the same time I was —

— You mean Ann just had the same dream that I did?

— Sure, from her viewpoint. Ask her about it later, when she wakes up. She’ll probably be too bashful to admit it at first….)

I looked over at Ann sleeping, and saw she was smiling. I smiled too, and went back to sleep with the same silly grin on my face. Later in the morning when I awoke I hesitantly asked Ann about the dream and sure enough, it was so.

/Looks like the fire needs another log…there we go.

I know that this is a long story, but I’ve got to tell it all if I’m to make my point. I ought to be finished before the night is done.

***

Dirk looked out of the window over several miles of trees and grass. He turned around and looked at me, as we stood in the tower with Roger, a couple from the Group, and the old man who had led us up.

(– Well Mark, he said, Do you see it?

— Where? I asked. I could see no trace of anything.

— There; see? No, not there. There. Dirk pointed proudly. – It just might be it, you know.

I looked again. Faintly, in the far distance, I saw a tiny sparkle, gleaming dimly in the morning sun. We thanked the old man and left to join the rest of the Group.

We traveled for three days before reaching the sparkle. During the three days we passed two waterfalls, but both were obviously the wrong ones. They were no more than small trickles. The sparkle itself was little more — it was a rushing mountain stream that shone brilliantly under the sun.

Dirk looked for a long time into the stream, while some of the rest of us drank from it. Then he said: (– This stream has to go somewhere. Let’s follow it and see where. There’s no point in losing any hope.)

The stream continued through the land endlessly, and so did we. We traveled for days by that marvelous rush of water, streaming through the valley and nourishing it with a flow of lifeblood. At nights we stopped by the stream’s banks to build our fires. The affection between Ann and me grew, and almost every night we would stroll away from the fire and the singing to be together.

We traveled on through the last days of autumn, when the few leaves that remained fell from the trees like a downpour of tears. The dead leaves crackled under our feet as we walked, with the stream tagging along at our side like a faithful dog. My God, I thought as I walked, these people have been walking like this for years, some for most of their lives. How can they be so patient?

Finally the stream poured into a river, and this we also followed. After awhile I began to take on the attitude that many of the people in the Group really didn’t care whether we found the waterfall or not. I never mentioned it, though, except to Ann.

/At this point I think I’d better speed up my story. We wandered on for month after month, and finally year after year without any real clue. At the age of nineteen, two years after I’d joined the group, I married Ann in one of the nameless villages along the way, while the rest of the Group stood by beaming. A few months and villages later, Roger married Sue.

During these years I felt more and more of a desire to find the waterfall; my dreams continued frequently, all of them with Ann…once, when I was angry with her, I mentioned that I couldn’t even get away from her in my dreams; we soon got over that, though. But in the same years a feeling of rebellion against the Group gradually grew in me. There were many things I did not like about it. There was the fact that whenever we reached a village, one of us would have to steal food. I realized it was a necessary action, but it was one I never grew used to, even though I was called on to do it at times. And there was feeling against looking back that also bothered me; I couldn’t accept it. Many were the days that I would see a familiar rock or tree or river and think, have I been here before? Ann was the only other one who noticed these places, as far as I knew. But neither of us ever said anything, except to each other…we could not break up the spirit of the Group — to do that would be to destroy our goals and perhaps ourselves along with them.

Time flowed swiftly. Dirk and his wife died, and Arthur, one of the older men, became the new leader. Roger and I were no longer true friends since our marriages, but we managed to get along. I never could confide in him, though — he was too fully absorbed in the Group to ever be able to understand me. On the Group’s basic beliefs he was as stubborn as anyone, and I made no effort to change him.

During those years I knew that eventually something of Ann’s and my beliefs would have to come out. Many in the Group were already suspecting some disagreement in us, although they said nothing about it.

Finally, one day, the truth was made plain./

***

We were near the top of a mountain when we approached an empty cabin. We’d encountered many of these before over the years — cabins built especially for travelers. They were completely empty except for an occasional salt shaker or rotten apple left behind by a previous group.

Only this cabin looked strikingly familiar. I felt certain that the Group had been here before, and for once I expressed some of that feeling —

(– You know, this place looks awfully familiar, I said to Arthur as we approached the door.

— Well, you know cabins do look alike.

— No, I don’t mean that. I mean familiar, like we’ve been here before.)

Arthur ignored this, and we walked on in with the others.

The inside of the cabin was equally familiar. Suddenly I thought of something. I walked over to one of the windows. Three years ago the Group had been here, and I’d carved my name on one of the window sills, along with the dozens of other initials, names and dates all over the cabin. The cabin itself reeked of memories, memories of countless people who had come and gone for over thirty years. And I had also written something: my name, the date, and the words THE GROUP.

I could no longer remain silent. I stepped up to Arthur, brought him over, and showed him the carving on the window sill.

He looked quite perturbed. (– Come outside with me for a minute, he said. He pointed to the door, and we walked out of the cabin. He stopped walking after a few yards and he turned to me.

— Now just what is it you’re trying to put over? he said. I don’t know how you did that now without my noticing, but whatever you’re starting I advise you to stop.

— Wait a second. I found that carving here, Arthur. And I remember the Group’s been here before — I can’t help it, but I do. We’ve been covering the same ground for God knows how long. I’ve got to tell you this because I want to find the waterfall as much as you do, and I can’t sit by which we search the same mountains and valleys year after year: I’m sorry, but I can’t stay with the Group as long as it stays this way. It’s the same with Ann —

Arthur looked at me incredulously for a moment. –You mean –? he said, and then stopped. But that’s not true, Mark. Why would we do that?

I had to tell him. — Because I’m beginning to think that none of you really want to find the waterfall. For all of you this is just a way of life, a reason for living — not a search. If you ever did find the waterfall, your purpose in life would be over. You’d have nothing left to do.

— Mark, you’re talking nonsense. Don’t you realize that we have no alternative about looking back…if we looked back our ambitions would be drained. Do you think it would help any, looking back on all the generations that have lived and died looking for this waterfall? No; all it’ll do is indicate that our search is hopeless, and we both know that it isn’t. That’s what Dirk told me before he died; he told me that the Group had to look at each day as a special day, new and unique. No, Mark, you have it all wrong. We want to find the waterfall, and to do so we must do this —

— Well that still doesn’t explain that carving on the window sill, I said. I stared at Arthur with bitter eyes, and then turned and walked back into the cabin.)

That night Ann and I left the Group. We left behind no words of regret or wishes for luck — we just left the fire, which was built near the cabin, and departed.

The cabin was located close to a mountain top, and we decided to reach the summit and stay there for the night, then go down the other side of the mountain in the morning. We were still determined to find the waterfall, and were convinced that we could do it away from the Group.

For a few moments we felt bad about leaving, as we were climbing the steep path to the summit. The night was dark and starless, and there was a heavy wind wheezing through the trees. ( — I felt kind of bad, Ann said as we walked, By not saying anything when we left I mean. It’s hard to leave something you’ve been with for most of your life, even if it’s the wrong thing. Don’t you think so?)

I didn’t answer. Instead, I stopped and looked behind me down the path. I saw the light of the Group’s fire in the distance, and I could still hear their singing. I stopped and listened to their favorite song, which sounded now just as it had sounded years ago when I’d joined the Group —

(— Don’t look back behind you or you’ll see the honest truth,

Don’t look back behind you or you might see Betsy Ruth….)

( — Come on, said Ann, who was already getting ahead.

— Okay, I said, and quickly followed.)

That night there was a loud wind on top of the mountain that kept us awake. For awhile we thought it was the sound of the waterfall. It was the sound of a great being dying, or perhaps of one being born. It is the sound you hear when water is being poured on your head and your hands are over your ears. It is a sound that makes you want to run and hide.

( — It’s the wind, I said.) After awhile we were asleep.

***

We began our search the next day and continued for over two years. During this time neither of us was very happy. The waterfall was no longer something to ponder about: it was an obsession. Sometimes at night by the fire Ann would cling to me and say ( — Let’s stop our search, Mark. We never will find the waterfall. Let’s stop and settle down and live a life instead of just prolonging one….

I would always try to change her mind. — Just another month or so, I would say. Then we can give it up.

Then, one night, it changed. It happened on a spring night.

It was a cool starry night with a breeze that touched the trees like fingers strumming on a guitar. We were walking down a path that seemed vaguely familiar to me when we came to a graveyard. (– Let’s stop here for the night, I said. It’s getting late, we need our rest.) We approached the graveyard, and saw nearby a campfire site. It was then that I realized we were in the graveyard of the village I had grown up in.

I told Ann. (– I wonder, I said, if I should stop in the village to see my parents. They’ve probably forgotten me almost completely by now. …maybe it would be best to just keep going – seeing them would drag up so many bad memories –)

I built a fire at the site, and after a small supper we walked into the graveyard to view some of the tombstones. I was almost afraid to see who had died in the village over the past seven years.

The bright moon illuminated the tombstones as it had before. I looked at some of the newer inscriptions, and found that many of my childhood friends and acquaintances had died. I wondered, what had my parents told the rest of the village when I left?

I turned to Ann. (– Ann, I’ve changed my mind. I think I want to stop in the village and see my parents again. I’ve kidded myself that I don’t care about them but I do; I would like to see them again. I’d like them to see you too, naturally. We can just stop for a short while. Okay?)

Ann nodded, and we continued to look for awhile at the tombstones. Graveyards also gave me an unusual feeling when the Group had stopped by various ones in the past. I always took a morbid kind of fascination in reading epitaphs –-

I stepped by the grave of my grandfather, and lingered once more over his inscription: HE KNEW THE WATERFALL IN HIS LIFE, AND NOW PERHAPS HE IS THERE. I had wondered about these words all during my years with the Group. Had he known? Was he there now? And who had written the epitaph?

I turned, and suddenly noticed that there were two new graves right alongside the one of my grandfather. I stopped to read the headstones, and saw that they were the headstones of my mother and father.

I knelt by their graves and wept silently, realizing at last all of the lost years I had spent away from them. Had they given up hope for my return?

I noticed then a small plot of ground next to their graves. Was that plot for me? Did they purchase it with the hope that I might return here to die some day?

Ann saw me weeping, and I showed her the tombstones. She sat by me, and I held her in my arms for a long time, saying nothing.

Finally I released her, and got to my feet. (– Ann, I said, You’re right. We should stop our search. Right here, as a matter of fact. I’d like for us to stop here, and go on into the village to live. I’ll get a job, and maybe I’ll be able to get our cottage and our farm back eventually.) I stopped to look down the hill, down the gentle flow of land to the village. It was still early in the evening, and there was a twinkling of lights from many of the cottages. It was good to be home.

***

/Well, I guess that’s all of my story, or at least just about all.

The next morning, after sleeping at the campfire site, we walked into the village….I got a job working at Mr. Ander’s store, and we stayed in a little cottage nearby. No one was staying at the old cottage — Mom and Dad had willed it to me in the hope that I’d return some day, as I did — but I decided it would be best to get some money to start out on before living there and running the farm.

Well, as I guess you all know, Ann and I now live in that old cottage where I grew up, and we’ve had two kids, plus another on the way. We make plenty to get by on from the farm, and I guess things have been going pretty smoothly.

By the way, I found out when I got to the village that Mom and Dad had died from that bad epidemic that went through the village like a storm a couple of years before. I was pretty determined I guess when I decided at last to settle down here. I’d spent all of seven years searching for something that probably doesn’t exist, and I was glad to stop. You were glad too, weren’t you Ann?

I see you look kind of surprised by my saying the waterfall might not exist. Well let me tell you something about that. Maybe it does, and maybe it doesn’t, but I feel that it was when I realized that the waterfall was a dream that I grew up. Sure, maybe it exists. I know every one of you wonders about it occasionally, and so do your kids. But that’s only natural…just look at it this way: if it exists, and everybody knew it, what difference would it make except in making everybody miserable looking for it? And when we don’t know for sure whether it does or doesn’t, then we know we’ve got something to look forward to when we die. But while we live, there’s no point in going on a wild goose chase when you can still see that waterfall every night when you dream.

I know, though, that a lot of you worry about it like I did once, and that’s why I called you all together to tell my story, so maybe you’ll understand. You’re happier here, believe me, than you’ll be off looking for any waterfall.

Oh, one other thing. It’s possible that someday the Group will pass through this village. If they do, be kind to them. Give them some food. Ask how they’ve been. Don’t mention me to them…it might bother them, although I think it’s quite likely that they’ve forgotten all about Ann and me by now.

Well I guess that’s about it. When your kids ask you tomorrow morning what this meeting was about, just say grownup matters. That’s what my parents always told me.

Well, goodnight all. I hope you all sleep well and have pleasant dreams of the waterfall. I know I will./