Published in Omni circa 1982. I owe this assignment and all my others at this magazine to the late Kathleen Stein, my editor there — a former classmate at Bard College and flatmate in New York during one summer. — J.R.

The Arts: TV

Jonathan Rosenbaum

How far can the human braln go in delvlng into its own workings? An

ambitious, new eight-part television series — being produced by WNET

for airing this fall — broaches this question at the same time that it

partially answers it, byproviding us with a veritable Cook’s tour

through the state of contemporary brain research. “What curious art the

brain, too finely wrought, /Preys on herself, and is destroyed by thought,”

glumly opined eighteenth century writer Charles Churchill, in an epistle

addressed to artist William Hogarth. But Churchill’s philosophical lament,

quite apart from its odd characterization of the brainas essentially

feminine, can’t hold water in relation to the healthy self-preying instinct

adopted, by the makers of The Brain and all that it uncovers.

“It’s totally addictive to go into this,” science editor Richard Hutton, a

writer and producer on the series, admitted to me about his own perusal

of brain research, in preparation for the eight one-hour shows. At the

same time, he acknowledges the sheer technical difficulty of representing

a subject that is so tough to visualize: “It’s amazing to try to do a series

when the star of the series is something g you can’t really see.” When I

asked him whether any of his own notions about the brain had become

altered during this survey, he replied without hesitation, “Everything.

The brain is the most complicated organ there is -– and the most

complicated entity there is that I’ve encountered. It’s fascinating — ”

Certain aspects of this fascination of Hutton and his cohorts for their

subject can be gleaned from the titles of the eight programs. In order,

these are “The Enlightened Machine,” “Vision and Movement,” “The

Animal Brain,” “The Chemistry of Emotion,” “Learning and Memory,”

“The Thinking Brain,” “Madness,” and “The Brain Age”. In order to

make the concepts in each program legible to a lay audience as well

as stimulating to a more sophisticated one, the series focuses a lot

of its attention on the stories of actual brains belonging to real

people. This includes everything from the personal struggles of

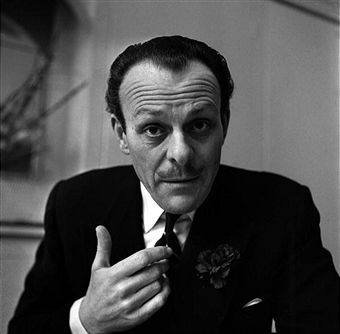

comedian Terry-Thomas with Parkinson’s disease in his daily life

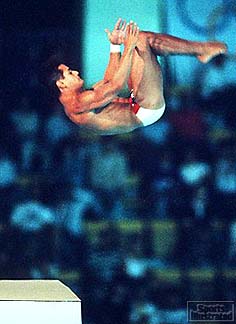

to the neural networks of platform diver Greg Louganis that are

in operation whenever Louganis executes a reverse 3 ½ dive with

a 1 ½ twist.

Also featured are the personal stories of many lesser-known

individuals — in some cases, people whose unusual brain

conditions have profoundly affected their day-to-day

existence. Philosopher Geraldo Guerniero, blind since birth,

has learned to “see” with his back through the use of a handheld

video camera that transmits visual signals to a grid of pressure

points on his back. Mitch Heller, who lost his sexual drive and

potency after a serious brain injury, managed to father a little

girl after being fitted with an “artificial hypothalamus” on his

belt which automatically supplies certain chemicals to his brain.

Mark Larribus went from being a gentle man to an extremely

violent one when a cyst developed on his brain, and then

returned to his gentle state after the cyst was removed. And,

by means of fictional recreation — a ten-minute sequence in

“The Chemistry of Emotions” that represents the only use of

docudrama in the series — The Brain also takes up the

curious, classic case of Phineas Gage, a railroads foreman

in the nineteenth century who underwent a disturbing

personality change after his cortex was severed from his

limbic system during an accidental explosion.

“The Animal Brain” focuses on those “primitive” aspects of the brain

that are essentially baggage from our animal ancestors, concentrating

on rhythms and drives through an examination of the hypothalamus

and pituitary — including the individual cases of Mitch Heller and

Mark Larribus, cited above. The biological clocks in the brain that

measure day and night and chart the seasons form the basis of two

other interviews in this segment.

One of these is with a French scientist, Michel Siffre,

who spent six months underground in order to

investigate the performance of his own biological

clock. Siffre found that without any sort of time cues

at his disposal, he was running on a 25-hour day;

after a month, he adjusted to running on a 48-hour

day. The implication is that we know how to

regulate ourselves without even the sun to guide us.

The gist of the other interview was vividly

described to me by associate producer

Peter Bull: “We all sort of get the blues in

the winter, but there are people who go

into the depths of depression, when they

sleep 12 to 14 hours a night, eat a lot and

can’t do anything — starting in the fall, when

the days are getting shorter, and ending in

the spring. They come out of their cocoons,

as it were, like butterflies; it’s unbelievable.

We did a whole sequence around a woman

like this, Pat Moore. The way they’re treating

her is amazing: when the winter months come

along, they start waking her up early in the

morning, and she sits in front of these full-

spectrum lights. Then late at night, before she

goes to bed, she does the same thing. So she

sort of artificially extends her daylight, to make

it like a summer day, and she comes right out of

her depression.”

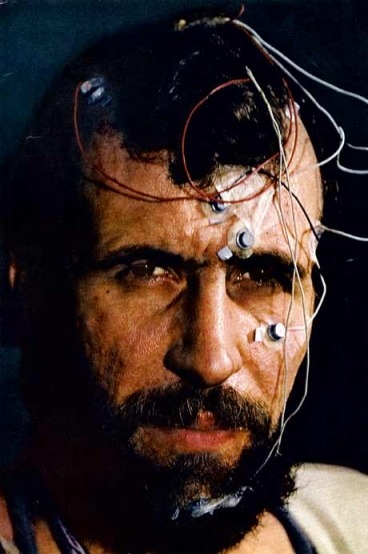

In order to visualize certain brain functions, the

show is utilizing an arsenal of up-to-date techniques,

including computer animation, digital screen

simulation, time-lapse microphotography and

three-dimensional modeling. In Los Angeles,

animator John Allison has been building elaborate

models of the brain, many times larger than life,

and then using tiny cameras with minute

boroscope lenses that can travel up and down the

blood veins in this model.

In spite of such visual aids, The Brain ultimately

faces the challenge of having to explain various

processes to an audience that is more accustomed

to thinking about the brain in terms of specific

organs. Because the actual structure of how people

look at the brain is largely what’s at issue, Richard

Hutton and Peter Bull are both hoping that the

series will turn around some of our more

outmoded thinking habits about the brain: the ways

that we think about memory, for instance.

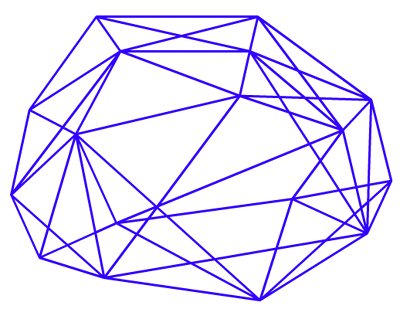

While many of us tend to think of our separate memories being

stored away as if in a bank vault, at least one commentator

has suggested that a hologram might provide a more accurate

visual model for the process of remembering. (If you remove

an entire section of a hologram, it can still basically function

as a complete entity; so too, it appears, can the brain.) As Bull

describes psychologist Daniel Hebb’s theory of cell assembly,

“You don’t have one cell that has, say, your memory of your

grandmother’s face, or that evening you spent with your

friend at the restaurant. You have a whole bunch of cells

that are interconnected, which, when activated by an

associative link which stimulates a series of cells,

generates your memory of having that particular

dinner.” In short, memories are put together out of

an elaborate cross-indexing system.

The final program in the series, “The Brain Age,”

will feature three dramatic stories centering on

the brain and self-awareness: the phenomenon of

rapid eye movements in fetuses, which suggests

the possibilities of REM sleep and dreams in a

prenatal state; the case of Tony, a multiple

personality in his late thirties who has at least

as many selves as he has years, and whose

fragmented consciousness offers another

variation on the awareness theme; and the

plight of a 51-year-old musician and music

teacher named Eleanor who is shown during

the middle stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

For Hutton, an important part of each of

these segments is not so much what we know

about the brain as what we still don’t know.

We don’t know, for instance, that fetuses

dream -– only that they have REMs, and that

REM sleep in infants and adults marks the

stage at which dreams occur. We don’t know

the precise relationship between the brain

and multiple personality, either -– unless

we note the brain’s capacity to tune out

distractions, which multiple personality

exaggerates to a pathological degree and

makes involuntary. And we hardly know

anything about Alzheimer’s disease, which

Hutton considers the biggest clinical

question in brain research today.

“Alzheimer’s disease is a memory story, but not really a memory

story,” Hutton notes. “What it does, ultimately, is change behavior

and personality. It’s a destruction of global awareness. If you look

on awareness as something that reaches an evolutionary fulfillment,

if you wish, in human beings, than Alzheimer’s disease probably

destroys the most human functions we’ve got.” In the case of

Eleanor, we see a woman with a master’s degree in music who

taught in public schools for many years and was in charge of

music at her church. “Her daughter followed her in music, and

now has taken over most of her roles in church. Eleanor is still

hanging on, but she’s lost a lot. She can sight-read any piece

of music you put in front of her, but she can’t make a cup of

coffee. It’s real sad.”

In order to rethink what the brain is, with or

without self-awareness, it seems that we need

to reflect more on interactions and processes

and less on individual parts in isolation from

one another. Indeed, from the available

evidence, it appears that interconnections

will be the message as well as the medium

of The Brain, promising an intriguing

kaleidoscope of possibilities. “If you had

to take a part of the brain that meant

something,” Hutton argues, “you wouldn’t

just take the right or left hemisphere.

That, for neuroscience, is bullshit. It’s the

synapse, where two cells talk to each other.

When we understand the synapse, a lot

of things are going to fall into place. That

involves the chemistry of the brain and the

anatomy, too – because you have to worry

about which cells of the brain are talking to

which, and why they get together. If

consciousness or self-awareness or perception

emerges, as most people think, from the

organization of the brain, then dealing with

the synapse when you think of something, or will

something, or want to move your finger –- these

are all really important thoughts.”