An unpublished essay written in June 1988 for the Chicago Reader. One of my few regrets about my 20 years at the Reader, unlike the year and a half I spent (1979-1981) at New York’s Soho News, was that whereas the latter allowed me to review books and movies concurrently, the Reader was interested in me only as a film reviewer, so any attempt to write about books for them was discouraged. I did make a point of reviewing two of Thomas Pynchon’s late novels for them (Vineland and Against the Day) –- having previously reviewed Gravity’s Rainbow for the Village Voice and having much later reviewed Mason & Dixon for In These Times between the two Reader reviews (all four of these reviews, incidentally, plus my earlier review of The Crying of Lot 49 for a college newspaper, can be accessed on this site).

I wrote the piece below on spec when Michael Lenehan was the paper’s editor and he told me I’d have to do a lot of rewriting before it could be published, so I bowed out. I can’t recall precisely what the “fantasy postscript” to this piece would have been –- the page (or pages) containing this conclusion, assuming that I’d written one, is now lost — so I have to apologize for ending it with either a cliffhanger or a provisional quote from a much earlier piece of mine.

If I were rewriting this piece today, I’d have to factor in the biographies of Welles by Brady and Callow, among others (covered in my 2007 book Discovering Orson Welles and here), and the excellent posthumous biography of Salinger by Kenneth Slawenski, which I haven’t written about, first published in the U.S. early this year. But I’d probably stand by my estimation of “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” which, incidentally, exerted a strong influence on “If Looks Could Kill,” a section of my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980). — J.R.

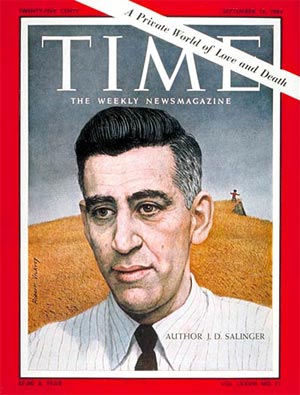

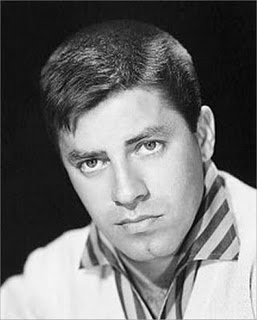

It’s a tribute to such otherwise mainly dissimilar American artists as Orson Welles. J.D. Salinger, Jerry Lewis, and Thomas Pynchon that all four tend to remain such indigestible premises as artists in relation to standard media tabulations. The usual method of “keeping score” of artistic careers in competitive cultures is not merely to tote up works, but also to log in appearances and visible deeds, and often to measure the works in relation to a synthetic media profile composed of these appearances and deeds.

For many Americans, the deeds and appearances of both Welles and Lewis are so much more prominent than their works (apart from Welles’s Citizen Kane) that these works scarcely exist for them at all. The filmographies of both men belong basically to specialists; how many average citizens can be called upon to name the last completed works of Welles, or the Jerry Lewis movies that Lewis wrote and directed himself? Salinger and Pynchon, by contrast, have opted for public careers which are devoted almost exclusively to works, restricting their deeds and appearances as much as possible — which hasn’t gone down well with the media either. Artists who choose to withhold from public view either part of their work (Welles, Salinger, and, to a much lesser extent, Lewis, whose mainly noncomic 70s feature about the Nazi death camps, The Day the Clown Cried, has never been released), or the ingredients that ordinarily make up a media profile (Salinger and Pynchon) are in a way asking for trouble –- at least from those sectors in academia and the marketplace which demand detailed bios and orderly oeuvres packaged for immediate consumption.

Some of these reflections are prompted by two interesting recent events — an Orson Welles conference and retrospective held in New York last month, and the recent publication of Ian Hamilton’s In Search of J.D. Salinger. The elaborate myths that surround Welles and Salinger (as well as Lewis) are curiously similar in the degree to which they provoke extreme instances of devotion and/or rancor relative to the perceived or identified narcissism of the figure in question — passionate personal responses which may have as much to do with certain individuals’ sense of their own identities as they do with the elusive identities of Welles, Salinger, or Lewis. In Freudian Oedipal terms, Welles and Salinger in particular are occasions for “acting out,” effectively enlisted as imaginary family members and thus appropriated as the raw material for a variety of fantasies. Without being in any real sense comparable as artists, they have served as the focus for psychic investments that have tended to polarize their fans and detractors — and to warp their biographers to an alarming extent.

In the case of Welles, this resonance is intensified by the volume of invisible work that he left behind — not only dozens of elaborated but unrealized projects, but also half a dozen feature films, most of them financed by Welles himself, which remain either unfinished or left in fragments for a variety of reasons. Exciting glimpses of five of these unseen features, one per decade since the 40s, were offered at the New York retrospective. In the years ahead, once the proper arrangements are made, it is conceivable that the Welles oeuvre that we now possess may grow from roughly 24 hours to as much as 36. It is already apparent from the examples recently shown that if his body of work should eventually increase by a third (an optimistic but not implausible estimate), our overall sense of the range and direction of Welles’s work will be substantially broadened.

The range of Salinger’s work is obviously a good deal narrower, and as long as he remains alive [in 1988], we have even less chance of computing the breadth of an invisible oeuvre than we did with Welles when he was alive. All we know, really, is that Salinger published 21 uncollected short stories between 1940 and 1948, a novel called The Catcher in the Rye in 1951, a collection of nine other stories in 1953, and five more pieces of fiction between 1955 and 1965, the first four of which have been collected in Franny and Zooey (1961) and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction (1963). (For the record, all 22 of the “uncollected” stories were brought out in a two-volume pirated edition in the 70s, and were available in some bookstores until Salinger exerted legal pressures to force them off the market.)

In Ian Hamilton’s new book about Salinger — finally published this spring after two previous drafts were blocked from publication by Salinger’s lawyers, for quoting or paraphrasing passages from Salinger’s personal correspondence — the author reports the rumor that Salinger “has at least two full-length manuscripts locked in his safe.” But insofar as one of the few solid facts that we know about Salinger is that he works constantly, it is entirely possible to imagine that, if he is continuing to work at the same steady rate that he did between 1940 and 1965, he should have six more volumes completed — or roughly the same amount that he has already published — by 1990.

Another rumor one has often heard, not printed in Hamilton’s book, is that Salinger intends for this invisible work about the Glass family to be published, but only after his death. If this should happen, it will surely entail an eventual reconsideration of his oeuvre that, from our present standpoint, is impossible to anticipate or predict. This is all the more bothersome from a reader’s standpoint if one considers the virtual cliffhanger contained in his last published work, “Hapworth 16, 1924”.

One of the longest stories Salinger has published — if, indeed, one chooses to call it a story, which is already a problem — “Hapworth 16, 1924” consists of a long, rambling letter written by seven-year-old Seymour Glass from a summer camp in Maine to his family. Also at camp is his five-year-old brother Buddy, Salinger’s designated alter-ego, who, in a brief introductory note to the letter written in 1965, announces that he has just read this letter for the first time, and intends to type it out verbatim — this act of fraternal piety presumably coinciding with our reading of the letter.

To a much more explicit degree than any of Salinger’s previous fiction about the Glass family, “Hapworth 16, 1924” presents a Seymour who is literally incredible, not merely as a precocious, multilingual boy wonder who would put Welles himself to shame — asking his parents to send him the complete works of Tolstoy and Proust (the latter in French for purposes of rereading), along with selections of dozens of other luminaries of world literature — but as a mystic seer who foretells the future in intimate detail and perceives the previous incarnations (or “appearances”) of himself and others. He even predicts a party two years in the future attended by himself, Buddy, and their parents which will (a) result in all of the Glass children becoming radio stars on a national quiz show (“It’s a Wise Child”), and (b) eventually lead to Buddy, in ripe middle-age, writing a story about this party — a story which, from Buddy’s aforementioned prefatory note, we already know that Buddy is working on in 1965, before reading this letter.

Talk about cliffhangers! After two obstinately wandering nonnarratives of wish fulfillment that conclude the Glass saga as we know it to date — “Seymour: An Introduction” and “Hapworth 16, 1924” — this evoked story about a 1926 party promises a return to the precise scenic and dramatic splendors of “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” which I regard as far and away Salinger’s best published fiction, arguably as good as anything by Fitzgerald or Lardner. From the limited evidence, however. One could just as easily assume that the story itself is a fiction of a fiction — like Buddy’s account of Seymour’s unpublished poetry in “Seymour: An Introduction,” endlessly described but never quoted, or, even worse, like Truman Capote’s Answered Prayers, a teaser for a revelation that never materializes.

In point of fact, the eponymous boy hero in “Teddy,” published twelve years earlier, had gifts which were quite similar to Seymour’s, and the overall shape and internal consistency of the Glass universe have been remarkably uniform, in matters both great and small, since the mid-50s. It is perhaps only the combination of relatively nondramatic and nonarrative fictional structures with the relatively explicit details about Seymour’s superhuman capacities which make Salinger’s last two published pieces so disconcerting to fans of his previous work. Whether they represent a permanent or temporary abandonment of “stories” in the ordinary sense is impossible to determine. Because of Salinger’s continuing refusal to publish, it is all too easy to reach totalizing conclusions about the overall directions his work has taken — a trap which Hamilton and many critics seem to have no compunctions about falling into. As in the case of Welles, there is an implicit equation made between the totality of an artist’s work and the selected portions which are currently visible — a reflection of the media’s apparent need to make final judgments even when the basis for making them is lacking.

The problem is, Salinger’s Glass saga, through its very incompleteness, expresses the same Zen-like suspensions that its characters often evoke. (As Samuel Beckett remarked of the painter Tal Coat,“Total object, complete with missing parts, instead of partial object. Question of degree.”) This leaves one at a loss to determine whether these lacunae are wholly willed and calculated — pointing to a complex remapping of aesthetic strategies designed to express the unsayable — or a necessary by-product of the vicissitudes of piecemeal publication. Mutatis mutandis, many of the same unresolved tensions can be found in some of the late works and fragments of Welles, even if their haphazard forms of release contrast sharply with the controlled flow (or nonflow) of Glass installments.

The desire for biographical information which yielded two very unsatisfying biographies of Welles the year of his death, and now Hamilton’s even more unsatisfying book about Salinger, is in a way a displaced response to the gaps and mysteries in the already available works of these artists. Barbara Leaming’s near-idolatrous Welles biography, written with Welles’s friendly (if belated) cooperation, proved to be as unreliable and as incomplete as Charles Higham’s rancorous biography, written in spite of Welles’s unfriendly lack of cooperation. Hamilton, by his own account, started out wanting to write an admiring and respectful book (apparently rather like Leaming’s) which would eventually lure Salinger out of his silence and confinement; encountering resistance from the start, and eventually two court injunctions, he wound up writing a small-minded and vituperative book more like Higham’s.

Regrettably, while posing as a serious literary scholar, Hamilton offers practically nothing of value as a critic of Salinger’s work. His major conclusion — that Salinger painted himself into a corner by improbably fancying himself a saint like Seymour, ending up, like Seymour in “Hapworth 16, 1924,” with the Glass family as both his “subject and his readership, his creatures and his companions” — is strictly ad hominem, unviolated by even a hint of literary insight.

After all, it’s not the business of critics to inquire into the personal worth or mental stability of artists, and the pathos of Hamilton’s legal difficulties can’t hide the fact that Salinger has never been even remotely duplicitous about his desire to be left alone. (In all fairness to Hamilton, however, his efforts can’t be compared to those of Betty Eppes’s “What I Did Last Summer” in Paris Review No. 80 — a report “arranged” with the assistance of George A. Plimpton of a tacky con job perpetrated on Salinger near his home by an attractive Baton Rouge reporter with virtually no interest in his work who was hot for a scoop, armed with a camera and concealed tape recorder. If Paris Review can lend credence to such sleazy tactics, it shouldn’t be surprising that Hamilton can find his more discreet snooping “serious” and “literary”.)

The recent arguments made by Hamilton and others about Salinger’s legal maneuvers putting a blight on future biographies of living figures seem revelant mainly to the kind of academic and journalistic hackwork that goes after individuals rather than the works or deeds that make them worth writing about. The elusive public identities of Salinger, Pynchon, and even Welles can’t really be separated from the evident seriousness with which they go about (or, in the case of Welles, went about) their work, and it’s worth recalling that William Faulkner, perhaps the most serious novelist this country has ever had, was similarly reclusive when it came to prying media.

As suggested earlier, the desire for information about Salinger can be interpreted as a displaced desire for for further edification about his work. Back in the early 60s, when he was still publishing books, Salinger tried to cope with that desire by offering “intimate” statements to the reader in the flap copy and dedications of his last two volumes. More recently, the no less publicity-shy Thomas Pynchon dealt somewhat more effectively with his own readers’ curiosity about him by writing a lengthy, quasi-autobiographical autocritique of his five published stories when he collected and introduced them in his book Slow Learner (1984), becoming in effect his own critic. Whether this will hold off the fact-hungry hoards whenever his next novel appears remains to be seen. (The coy re-evaluation of The Catcher in the Rye and “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” in terms of their relevance to Seymour Glass in “Seymour: An Introduction” is quite another matter, having been made by Buddy, not Salinger.)

The degree to which Salinger’s fictional world is painfully split between insiders and outsiders, snobbery and acceptance, Wise Children and Fat Ladies, points to an exacerbated social tension that hovers over most of the issues raised by his work, spilling over onto the mythical figure of Salinger himself. Having once seen Salinger at my high school graduation — an event he attended because the oldest son of his editor and best friend, William Shawn, was a classmate of mine — I can testify to the power exerted by this tension over my own troubled adolescence. Several months earlier, I happened to be present in the Shawns’ apartment the same day that Time‘s cover story on Salinger appeared, when much of the household was in a state of near-hysteria about the violations of truth and privacy that this entailed, at which point “Jerry” himself phoned — to all appearances, judging from the account of his call, a good deal calmer and more wryly humorous about this crisis than some of his friends were.

I report this limited information not to brand myself as any kind of “insider” (which I decidedly wasn’t), but to indicate how even this minimal an acquaintance fails to match up even remotely with the overall portrait of Salinger presented in Hamilton’s book, which ultimately makes him out to be some sort of raving lunatic — perhaps the understandable projection of a would-be biographer who has been devoting years to pounding his fists against a closed door. It seems equally probable that, because of Shawn’s own self-effacement and extreme sense of privacy, his role in Salinger’s development as a writer is a major part of the story that remains to be told. (Whether it will be or should be is another matter, for surely the right to silence is an integral part of freedom of speech.)

Apart from dutifully attempting without success to interview Shawn, Hamilton avoids looking into this matter too closely. But clearly Salinger’s relationship with The New Yorker, which dates back to the early 40s, is central to his work; none of the Glass stories has appeared in any other magazine, and Salinger has neither published nor collected anything except Glass material since 1955. Perhaps it’s Hamilton’s distance as an Englishman from the American scene which prevents him from probing too deeply into the question of The New Yorker‘s relation to American upper-crust culture and values — a weighty topic which has yet to be explored seriously in any detail by anyone — or broaching at all the matter of Shawn’s gradually diminished power at the magazine over the years, which culminated in his recent forced retirement.

Even after one acknowledges that the magazine guards its house secrets even more closely than the Thatcher Memorial Library in Citizen Kane, it is surely not unthinkable that Salinger’s silence since 1965 might at least partially have something to do with Shawn’s waning influence over the magazine’s contents. (Other contributing elements, discussed at length by Hamilton, might include Salinger’s growing disenchantment with publishers, as well as his sensitivity to hostile criticism.) One also has to weigh the mainly specious question of Salinger’s mental stability raised by Hamilton and others — the hypothesis that “Hapworth 16, 1924” shows a writer in the process of cracking up — next to the indisputable fact that no one has ever questioned Shawn’s eminent sanity as an editor. It is worth adding, moreover, that the incidental local and period details of Salinger’s last published works appear to be as impeccable as those in his previous fiction. As a “New York” writer, Salinger needs to be read as a regionalist to the same degree that Faulkner is; the borders of the Glass world are at once as confined and as universal as those of Yoknapatawpha County. It is only in relation to the spiritual and supernatural details of this world that the issue of its “reality” and how one chooses to relate to it is raised.

In any case, every Salinger reader is entitled to his or her own fantasies about his fiction, at least as long as they’re not acted upon in a way that infringes upon Salinger’s ownership of this preserve. His continuing iron-clad control over the reprinting of his work includes the refusal to permit any film, stage, radio, or TV adaptations, ever since the mauling of “Uncle Wiggley in Connecticut” when it got translated into a Hollywood tearjerker called My Foolish Heart in the late 40s. This leads me to a fantasy postscript of my own.

My dream scenario runs roughly like this: Salinger finally relents and allows Jerry Lewis to direct a film based on The Catcher in the Rye (”Salinger’s sister told me if anyone would get it from him it would be me,” Lewis remarked in a 1977 interview), and civilization as we know it collapses. In the ensuing sociocultural upheaval occasioned by this deconstruction of two critical reputations, anarchy reigns supreme: mad dogs roam the street, The New Yorker shrivels to a cinder out of acute, well-mannered embarrassment; and all those distinguished gray eminences in my profession who fear and loathe Lewis for what he says about their own bodies and social discomforts — some of whom shrink in terror from Tati for the same reasons — run screaming off to the Hamptons and Berkshires to write their own fiction, never to return.