From the Chicago Reader (August 4, 1989). This was my second column about Do the Right Thing; my first one is here. — J.R.

It’s readily apparent by now that Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing is something of a Rorschach test as well as an ideological litmus test, and not only for the critics. It’s hard to think of another movie from the past several years that has elicited as much heated debate about what it says and what it means, and it’s heartening as well as significant that the picture stirring up all this talk is not a standard Hollywood feature. Because the arguments that are currently being waged about the film are in many ways as important as the film itself, and a lot more important than the issues being raised by other current releases, it seems worth looking at them again in closer detail. I don’t mean to review the movie a second time, but I do want to address some of the deeper questions being raised by it. Ultimately most of these questions have something to do with language and the way we’re accustomed to talking about certain things — race relations and violence as well as movies in general.

We all tend to assume that no matter how imprecise or impure our language may be, it still enables us to tell the truth if we use it carefully. Yet the discourse surrounding Do the Right Thing suggests that at times this assumption may be overly optimistic — that in fact our everyday language has become encrusted with so many unexamined and untruthful assumptions that it may now be inadequate for describing or explaining what is right in front of us.

Consider, just for starters, the use of the word “violence” in connection with Lee’s film. Some people have argued that the movie espouses violence, celebrates violence, treats violence as inevitable, or shows violence as therapeutic. (At one of the first local preview screenings of the movie, in Hyde Park, a paddy wagon was parked in front of the theater before the movie even started.) All these statements refer to instances of violence that occur toward the end of the movie, but none of them appear to be referring to all of these instances, which include the smashing of a radio with a baseball bat by the pizza parlor proprietor, Sal (Danny Aiello); a fight between Sal and the owner of the radio, Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn); the killing of Radio Raheem by white policemen who arrive on the scene to break up the fight; the throwing of a garbage can through the front window of the pizzeria by Mookie (Spike Lee), a black delivery boy who works for Sal; the subsequent looting and burning of the pizzeria by several nonwhites in the neighborhood; and the putting out of the fire by firemen, who knock down some people with the force of the water hoses. To make this list complete, one might also include the incident that sets off all the subsequent violent events: Radio Raheem entering the pizzeria after it’s officially closed for the day with his ghetto blaster turned up to full volume, accompanied by two angry blacks who have previously been turned away from Sal’s establishment for making disturbances — Buggin Out (Giancarlo Esposito) and Smiley (Roger Guenveur Smith).

No one appears to be arguing that the movie treats all of these events positively, so there must be an underlying assumption that not all of these events are equally violent. The “real” violence, according to this discourse, turns out to be the destruction of white property (the throwing of the garbage can, the looting, and the burning) — not the creation of a disturbance (the blasting of the boom box), the destruction of black property (the smashing of the boom box), the fight between two characters (Sal and Radio Raheem), or the destruction of a human life (the killing of Radio Raheem).

I don’t think that the people making these arguments automatically or necessarily assume that a pizzeria is worth more than a human life, but I do think that our everyday use of the word “violence” tends to foster such an impression. There are times when our language becomes so overloaded with ideological assumptions that, however we use certain terms, they wind up speaking more than we do.

Stepping outside the immediate context of the film for a minute, consider the appropriateness of terms like “black” and “white” — terms that we’ve somehow managed to arrive at by default rather than through any sharpening precision in our use of language. The evidence that our senses give us is that so-called “white” people aren’t white at all, but varying gradations of brown and pink, while most so-called “black” people in the U.S. are varying gradations of brown and tan. Thus the skin tones in question aren’t nearly as oppositional as the words that we use make them out to be. (It could be argued that capitalizing “black” only increases the confusion by further validating the concept behind the term as opposed to the visual reality.) A major reason why “Negro” ceased to be an acceptable word during the 60s was the belief that it was a “white” word and concept; unfortunately, “black” is a term that makes sense in a racial context only in relation to “white,” and if “white” is itself a questionable term, “black” or “Black” only compounds the muddle. (Consider also the consequences of this metaphysical mischief when one adds to the discussion Hispanics and Orientals, who are commonly regarded as neither white nor black, and Native Americans, who are arbitrarily designated in our mythology as red.)

I’m not arguing that we should go back to terms like “Negroes” and “Caucasians,” or that an arcane term like “colored people” is any better than “blacks” (it’s often been pointed out that “whites” are “colored,” too). The point is that we’ve reached an impasse in the language, and it ensures a certain amount of metaphysical and ideological confusion regardless of what we say.

So far I’ve been speaking exclusively of verbal language. When it comes to the conventions of film language and what’s known as the cinematic apparatus as a whole — the institution that regulates the production, distribution, exhibition, promotion, consumption, and discussion of movies — we may be in even deeper trouble, because the movie-related conventions that we take for granted aren’t nearly as self-evident.

To start with one very general example of this, consider the way that most TV critics talk about movies. If the movies released this year were ten times better than they actually are, or if they were ten times worse, the discourse of these critics would be more or less the same, because the critics’ functions in relation to this output would be identical. A major effect of this kind of reviewing is to keep the movie market flowing and to make the offerings of every given week seem important — a process that usually entails forgetting that last week’s offerings were made to seem equally important. The critics’ mission is not to educate us about the movies but to guide us toward some and warn us off others. Movies are either worth seeing or not worth seeing, and every week there are a couple of each.

Another example, this one more to the point: Many critics have commented that the expression “do the right thing” means something different to every character in Spike Lee’s movie, but not very many have agreed about whether the movie itself presents its own version of what “the right thing” is or might be. Many people believe that Mookie’s throwing of a garbage can through the pizzeria’s window is Spike Lee’s version of the “right thing,” but they arrive at this belief through a passive acceptance of certain movie conventions.

Spike Lee plays Mookie himself, and even though everyone knows that Lee doesn’t deliver pizza for a living there’s an understandable impulse to interpret his role as that of the hero or protagonist, according to the usual conventions governing writer-directors who double as actors (Woody Allen, for instance). In addition, there’s a temptation to interpret the filmmaker’s presence in the role metaphorically and autobiographically; for example, Mookie works for a white boss, and one could argue that Lee depends on “white”-run studios for the distribution of his movies (even though he insists on retaining “final cut,” which gives Lee an autonomy that Mookie lacks). An even more basic assumption is that all commercial movies have heroes and villains and therefore take relatively unambiguous stands about what’s the “right thing” and what’s the “wrong thing” in any given conflict.

But what if Do the Right Thing doesn’t have any heroes or villains? What if it doesn’t propose any particular action as being the right thing? What if, in fact, it postulates — as I believe it does — that given the divisions that already exist in the social situation that the film depicts, it’s not even possible for any character to “do the right thing” in relation to every other character? If the language that we speak is such that it can only express relative truths rather than absolute truths, it isn’t difficult to extrapolate from this that the cinematic apparatus that we take for granted is similarly tainted.

Even some of the most intelligent commentary about the movie suffers from certain built-in assumptions about it, which stem from unacknowledged assumptions about movies in general. Terrence Rafferty’s review in the July 24 issue of the New Yorker, for example, which manages to avoid or refute much of the nonsense that has been circulating about the film elsewhere, still falls into the trap of imputing certain motives to Spike Lee that exist outside the film’s own frame of reference.

“Raheem certainly doesn’t deserve his fate,” Rafferty argues, “but without [Sal’s] inflammatory racial epithet” — Sal calls Raheem a “nigger” at the peak of his rage — “Lee would have a tough time convincing any audience that Sal deserves his.” Rafferty is assuming here that Lee wants to convince the audience that Sal “deserves” to have his pizzeria burn down — an inflammatory accusation whose truth seems less than self-evident to me.

Rafferty continues with a string of rhetorical questions: “Does Lee really believe that . . . any white person, pushed hard enough, will betray his contempt for blacks? Does he believe, for that matter, the tired notion that anger brings out people’s true feelings? And does he also think that lashing out at Sal because he’s white and owns a business and is therefore a representative of the racist structure of the American economy is a legitimate image of ‘fighting the power’? If you can buy all these axioms smuggled in from outside the lively and particular world this movie creates, then Do the Right Thing is the great movie that so many reviewers have claimed it is. But if you think — as I do — that not every individual is a racist, that angry words are no more revealing than any other kind, and that trashing a small business is a woefully imprecise image of fighting the power, then you have to conclude that Spike Lee has taken a wild shot and missed the target.”

This sounds like impeccable reasoning, if one accepts the either/or premise and believes that Lee is smuggling these dubious axioms into his movie. But in fact the axioms and the smuggling both belong exclusively to Rafferty. The movie shows certain events happening and certain steps leading up to them; these events include one supposedly levelheaded pizzeria owner blowing his cool and a group of angry blacks trashing his establishment. At no point does the movie either show or argue any of the three axioms cited by Rafferty; at most, one might intuit that some of the film’s angry black characters associate their trashing of the pizzeria with “fighting the power,” but there’s nothing in the film that suggests that they’re right about this; nor does the film say that Sal is exposing his “true feelings” or that Sal is the equivalent of “any white person.” Indeed, the movie takes great pains to show that the characters who tend to talk the most about “fighting the power” in less hysterical situations — Radio Raheem, Buggin Out, and Smiley — are relatively myopic and misguided, and are seen as such by their neighbors; it also takes pains to establish Sal as a complex, multifaceted character who can’t easily be reduced to platitudes.

Rafferty claims that one must accept questionable axioms to find Do the Right Thing a great movie. I would argue, on the contrary, that the film’s distinction rests largely on its freedom from such axioms — a freedom that is part and parcel of Lee’s pluralistic view of all his characters. This view simultaneously implies that every character has his or her reasons and that none of them is simply and unequivocally right. To seize upon any of these characters or reasons and to privilege them over the others is to return us to the paradigm of cowboys and Indians, heroes and villains. We’ve lived with this either/or grid for so long, it’s probably inevitable that some spectators will apply it even on that rare occasion, such as this one, when a filmmaker has the courage and insight to do without it.

In place of either/or, Lee gives us both/and — epitomized by the two quotations that close the movie from Martin Luther King (condemning violence) and from Malcolm X (describing situations when self-defense may be necessary). Some people have argued that Lee’s refusal to choose between these statements proves that he’s confused, but this argument only demonstrates how reductive either/or thinking usually turns out to be. The film’s closing image is a photograph of King and Malcolm in friendly accord, not in opposition, and if the past of the civil rights movement teaches us anything at all about its future, then surely this future has a sizable stake in the legacies of both men. To view those legacies as complementary rather than oppositional is part of what Spike Lee’s project is all about.

Let’s look at Lee’s pluralism at the point when it becomes most radical — when the character who is the closest thing in the movie to a villain (without actually being a villain) is placed in a position where the audience is likeliest to agree with him. The character in question is Sal’s son Pino, an unabashed racist who despises working in a mainly black neighborhood, which he refers to as “Planet of the Apes.” (”I’m sick of niggers . . . I don’t like being around them, they’re animals.”) The moment in question is at the height of the pizzeria-trashing, when the rioters are tearing Sal’s establishment to shreds and raiding the cash register in a manic frenzy (certainly a far cry from anything one might call a heroic image). At this point the film cuts to a shot of Sal with his two sons watching from outside; Sal is screaming, “That’s my place! That’s my fucking place!” Then there’s a cut to Pino watching the orgy of destruction with disgust and saying, “Fuckin’ niggers.”

It’s easy enough to interpret this shot as the stock response of a mainly one-note character. But if one were to assume the vantage point of Pino and then select a single instant in the movie when his viewpoint came closest to being emotionally vindicated, or at least partially illustrated, for most people in the audience, this would conceivably be the precise instant that Lee has chosen. For about two seconds, Pino is allotted the privilege — a relative privilege, not an absolute one — of saying the right thing.

Just as Pino is the closest thing in the movie to a villain, Mookie is the closest thing to a hero. He occupies the space and the relative prominence in the film that would normally be accorded to a hero, but in spite of his overall charisma, his actions and attitudes are far from heroic. As Lee himself remarked to Patrick McGavin and myself in an interview earlier this summer, “He wants to have a little bit of money in his pocket [and] do as little work as possible.” (Some viewers have complained that few of the characters in the movie are shown working, apart from the cops, the Korean grocers, and the workers at the pizzeria; these viewers seem to have overlooked the fact that the film takes place on a Saturday.) Mookie’s sister Jade (Joie Lee), who helps to support him, and his Latino girlfriend Tina (Rosie Perez), who feels neglected by him, both deride him constantly through the film for not living up to his responsibilities, which include concern and care for his infant son Hector.

Mookie’s two major interests appear to be money and baseball; and while he is the only character in the film who serves as a link between the black and white people in the neighborhood, no one in the movie seems to regard him as a role model — with the partial exception of Vito (Richard Edson), Sal’s younger son, a relatively sweet tempered but not especially strong character who regards Mookie somewhat as an older brother in preference to Pino (which further intensifies Pino’s racial enmity). In comparison to his sister, Mookie seems utterly lacking in ambition, and while most of the people on the block seem to like him — Sal says that he regards him as a son, and both Da Mayor (Ossie Davis) and Mother Sister (Ruby Dee) show a parental concern for him — no one apart from Vito can be said to look up to him, and there’s certainly no hint that Vito’s support extends to Mookie’s eventual act of violence.

The only decisive moment in the film when Mookie appears to act on behalf of the local residents rather than in his own private interests — discounting the interests of Sal and his sons and the local policemen, none of whom live in the neighborhood — is when he sparks the riot by throwing the garbage can. But while Mookie clearly sets off the violence that follows, he doesn’t participate in it, and there’s no indication that he revels in the destruction either (which means the loss of his own job); near the end of the sequence, he can be seen sitting with his sister on the curb in front of the charred ruins, looking disconsolate rather than triumphant about what’s happened. Nor can it be said that he is suddenly made into a hero by his one violent act; when Mookie is seen with Sal the following day haggling about money, there is nothing to suggest that he has grown or been changed by the experience of the previous night — his behavior is exactly the same as it was before the riot.

The two most insightful remarks I’ve encountered so far about Do the Right Thing haven’t appeared in print; they’ve come from phone conversations with two friends and fellow critics who happen to be, respectively, the Los Angeles and New York correspondents for Cahiers du Cinema, Bill Krohn and Berenice Reynaud. Krohn views the film itself as a conflict between discourses, an approach that he traces back to Jean-Luc Godard in films of the 60s like La chinoise and 1 + 1 (the latter known in the U.S. as Sympathy for the Devil), films that were similarly misunderstood 20 years ago because people assumed that the violent discourses they contained — from French Maoists in La chinoise and from black radicals in 1 + 1 — were necessarily and unambiguously the views of Godard, rather than simply discourses that he was provocatively juxtaposing with other discourses. (Whether Lee has been directly influenced by Godard is a secondary issue, but it’s worth noting that two unorthodox uses of editing in Lee’s film are distinctly Godardian: Mookie’s initial greeting of Tina with a kiss is shown twice in succession, and there’s a similar doubling of the action, from two separate angles, when the garbage can goes through the pizzeria window.)

Berenice Reynaud believes that the basic conflicts in the film are ethical rather than psychological — particularly the conflict experienced by Mookie that leads to his throwing of the garbage can. The shot that precedes this action is probably the most widely misunderstood in the film; people who think that Mookie’s action seems to come out of nowhere may be thinking this because they’re misreading what’s happening in the shot. Immediately after the police cars leave the scene, carrying away Buggin Out (who is visibly being clubbed by a policeman as the car drives away) and the dead body of Radio Raheem, the camera pans slowly from right to left past a crowd of onlookers in front of Sal’s pizzeria. The people in the street are horrified and enraged by what’s just happened, and most of them — in fact, all of them who are speaking — are addressing Mookie, who is standing offscreen, in front of the pizzeria with Sal and his two sons.

In part because of the unrealistic and highly stylized nature of the shot — each character delivers a pithy comment in turn as the camera moves past him, rather like the TV interview with combat soldiers in Full Metal Jacket — it’s possible to misread the shot as a group of angry blacks who are simply addressing the camera. To be perfectly honest, I misread the shot in this way myself the first time I saw the film, although what the characters are saying is clearly addressed to Mookie: “Mookie, they killed him!”; “It’s murder!”; and so on. The police are no longer around, and implicitly these characters are all asking Mookie what he’s doing standing with the only white people in sight. Ethically speaking, they’re all asking Mookie to do the right thing, and he responds accordingly.

But according to what has already been established in the film, there is no absolute or absolutely correct choice available to Mookie; whatever move he makes will at best be “right” for some of the film’s characters and wrong for some of the others. He has been forced, in short, into an either/or position that falsely divides the world into heroes and villains — the world, in short, that most moviegoers seem to prefer.

If the audience members cannot think or feel their way into Mookie’s position, and can’t experience the challenge of those taunts about whom Mookie stands with, then Mookie’s act of violence will seem rhetorical and contrived — an act that the film is imposing on the situation from outside to make a polemical point. But for any spectator who agrees to identify with Mookie and his ethical crisis the moment assumes a certain tragedy — not a tragic inevitability, because Mookie could simply quit his job at this point rather than pick up the garbage can, but a tragic ethical impasse.

It’s been reported that a major reason why Do the Right Thing failed to win any prizes at the last Cannes film festival was the objection of Wim Wenders, the president of the jury, that Mookie didn’t behave more like a hero. Wenders’s implied critique is that Lee should have made Mookie into a role model, superior to every other character in the film — a character who would exalt the either/or principle, which would imply, in turn, that the world is as simple a place as most movies pretend that it is, where simple and unambiguous choices are possible. The world of Rambo, in short — a world that is, curiously enough, not normally accused of fostering and encouraging violence to the degree that Lee’s film has been.

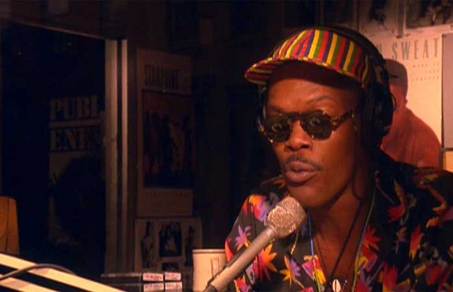

Ironically, it is the moment at which Mookie throws the garbage can that he comes closest to functioning as a Rambolike hero — and closest to demonstrating how false and reductive the notion of such simpleminded heroism can be in a world as cluttered, splintered, and confused as ours. If role models are needed, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X seem much better choices — not to mention Mister Senor Love Daddy (Sam Jackson), the local disc jockey whose patter periodically serves as narration; his most important message on a very hot day is for all of the characters to cool off.