From the Chicago Reader (October 5, 2001). My thanks to D.V.@VillalobosJara in Chile for reminding me that I wrote this. — J.R.

I periodically get letters from readers complaining that I write too much about movies they’ve never heard of, some of which come from countries they know little about. A good many examples of these kinds of films are playing over the next couple of weeks at the 37th Chicago International Film Festival.

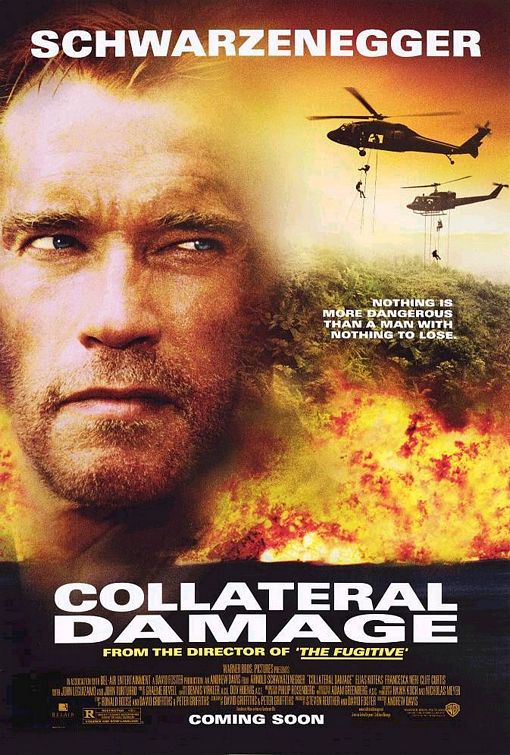

The reason you haven’t heard of most of the 80-odd features on the schedule is that they don’t have multimillion-dollar ad campaigns designed to make them seem as familiar as trees — or Arnold Schwarzenegger. Warners was doing a big campaign for his latest action flick, Collateral Damage, which is about international terrorists who kill his wife and child with a bomb. Before September 11, it was scheduled as the festival’s opening attraction, but Warners belatedly came to its senses and decided not to release it (David Mamet’s Heist was abruptly coughed up as a replacement). There were times in August and early September when posters for Collateral Damage seemed almost as prevalent as American flags have been the past few weeks.

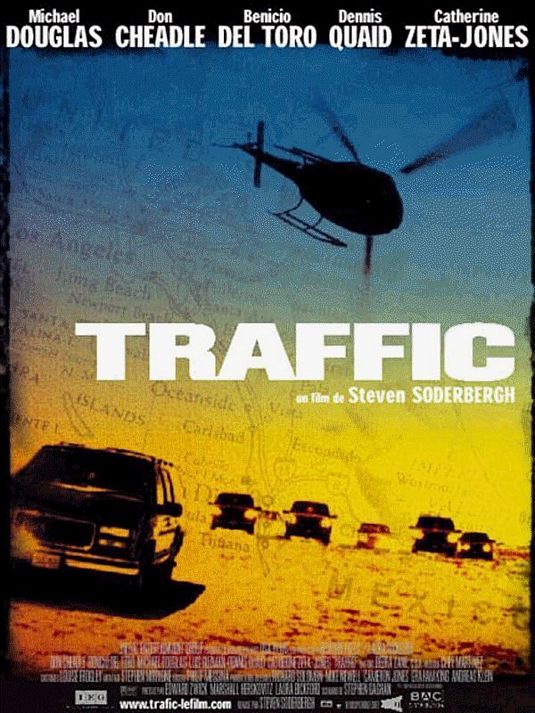

One of the American dream bubbles pricked on September 11 is the idea that we really aren’t part of the world — a delusion that seems inextricably tied to the conviction that we’re safe and invulnerable compared to other countries. It was just such a belief that seemed to characterize the beginning of George W. Bush’s administration and its willingness to say “fuck you” to the rest of the world (the Kyoto protocols, the ABM treaty) — an attitude seemingly predicated on the assumption that the rest of the world consists of wannabe Americans. Now there’s at least the hope of multilateralism given the renewals and reconfigurations of various international alliances — and the hope that those alliances might help curb American military excesses in response to the September 11 attacks. “European solidarity with the United States will depend on just what a global ‘war’ against terrorism entails,” announces a headline in my favorite conservative newsweekly, the Economist, though some people in the media apparently don’t need to know what it entails, preferring to gloss over such issues with nostalgia for the collective highs of the gulf war or even World War II and countless Hollywood references. Most often they refer to Pearl Harbor, though Titanic seems more appropriate. Even more appropriate, as University of Chicago film professor Tom Gunning recently suggested to me, might be Traffic, insofar as the “war on drugs” is the only reasonable parallel to any war we might try to wage on terrorism — both being wars that can never be definitively won.

I’m as eager as anyone to find and punish the terrorists — even if the U.S. helped to empower them as it has our other favorite foreign devils, such as Noriega and Saddam. But I’d feel a lot better about such an undertaking if I weren’t worried that innocent, impoverished Afghans are more likely to get killed than anyone else.

Maybe some Americans unconsciously think we aren’t part of the world because we simply are the world and everything else has something to do with subtitles, exotic vacations, fancy food, bad television, lots of weird people wanting nothing except to have what we have, and a certain amount of physical discomfort and danger. Isolationism has overtaken this country in recent years — a more extreme form in some ways than during the cold war, when the perceived split was between the “free world” and the “communist world” rather than between this country and everywhere else — but it’s questionable whether the world can sustain such divisions and still survive. So it’s encouraging that Americans may be changing what they usually mean when they say “we.” The world has become too small to tolerate claims of exclusivity, whether they come from American yahoo solipsists or Middle Eastern religious fanatics.

***

Should the U.S. declare war as a result of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon?

Yes: 62%

If Congress were to declare war, whom do you think it should declare war against?

Not sure: 61%

Afghanistan/Taliban: 15%

Osama bin Laden: 10%

Terrorists in general: 8%

Palestinians: 4%

Iraq: 4%

Saddam Hussein: 2%

No one, just declare war: 2%

– from a September 24 Time magazine poll

Needless to say, polls of this kind are problematic, especially because, as in movie test marketing, the questions the pollsters ask play some role in determining the responses and people are obliged to come up with snap judgments rather than careful reflections. Still, these poll results suggest that a lot of people accept the notion of collateral damage — at least as long as it doesn’t include them. It’s certainly telling that the pollsters collapsed “Afghanistan” and “Taliban” into the same category — implying that if we can’t declare war on one, the other will do just fine — and that twice as many people opted for declaring war against Iraq than against Saddam Hussein. (”U.S. Vows to Defeat Whoever It Is We’re at War With,” reads the lead headline of my current favorite nonconservative newsweekly, the Onion.)

Of course many non-Americans were wiped out by the attacks of September 11, which implies that they were regarded as collateral damage by the terrorists. We’re understandably shocked by those deaths. But shouldn’t we also be shocked by the collateral damage the U.S. has been inflicting on Iraq — without getting close to Saddam Hussein — since the beginning of the Gulf War? The sanctions and continued bombing have brought Iraq’s casualties to as many as a million, most of them women and children. How can a million deaths in an unsuccessful campaign to topple Saddam Hussein be seen as unfortunate but necessary — especially given that those deaths have only bolstered Saddam’s anti-American propaganda and motivated terrorist attacks against us?

Surely this has a lot to do with what we are and are not able to see. What people were able to see of the war in Vietnam led to massive protests and outrage. The handlers of the Gulf War knew this, and they limited what the media were allowed to cover. I doubt we would have witnessed quite so much euphoria in the U.S. over some of the hits on Baghdad if they hadn’t resembled animated-movie or video-game explosions. Many people were aware on some level of what was happening, and for that reason the euphoria was horrible, just as the celebrations of Palestinians over the recent attacks on New York and the Pentagon were. If we bomb Afghanistan, we’ll see very little and the consequences are likely to be so cataclysmic that we’d have nothing to celebrate.

Many people’s first, shocked reaction to the attack on the World Trade Center was that it was like a movie — because they couldn’t believe what they were seeing. For me, it was a movie that hurt like hell — the way an honest movie about the Gulf War might hurt if we could see it, one that told stories about innocent people leaping from buildings on fire, of severed body parts scattered under toppling piles of rubble, of parents and children and siblings desperately looking for missing family members. Unlike any Schwarzenegger movie, that would have been a movie for grown-ups.

Another movie for grown-ups might be one in which a U.S. president admits that there could be motives for a terrorist attack besides “hating our freedom.” Yet another might be one that views this country as a fusion of all others, with meaningful links to them that could be creatively strengthened. Why do we have to wait for a terrorist crisis before we become curious about the Middle East, and when are we going to start placing more of our focus on Middle Easterners than on their sometimes despotic rulers? And when are we also going to consider that there are just as many cultural variations on being Middle Eastern as on being American — and that sometimes these variations even overlap? As the American grandson of eastern European Jews, I’ve been taught to regard myself as Jewish in origin but not exactly Middle Eastern. Actually, I feel like I’m both, which doesn’t necessarily tie me to Israel; some American Jews prefer to overlook the fact that there are Jews throughout the Middle East. My point is that we all have many choices to make within our ethnic and national identities, and that denying these choices to others usually entails shortchanging ourselves.

We don’t get many chances to see movies that let us feel that this country is part of the world and that address us as individuals rather than as part of some mass market. But the 37th Chicago International Film Festival — which has one of the best lineups I’ve seen since coming to Chicago in 1987, perhaps because it has cut much of the filler of previous years and stuck more to the essentials — affords us numerous such opportunities. At the Toronto film festival, which I was attending when the World Trade Center was attacked, I asked a colleague — the lead film critic of a major newsmagazine, who was preparing to chair a symposium at another festival with Oliver Stone and Christopher Hitchens — what his panel would be about. “Basically, why we don’t have any more political films,” he said with a melancholy look. To which I replied, “What do you mean ‘we’? Have you seen The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein?”

Now here’s a film — an American film — you’ve almost certainly never heard of. The writer-director, John Gianvito, says he made it to keep himself from going crazy. He has a fine eye for desert landscapes, a poetic sensibility, and a comprehensive knowledge of cinema (he’s associate curator at the Harvard Film Archive, and in homage to silent film he names one section of his movie after D.W. Griffith’s Orphans of the Storm). But he isn’t a hustler or a “professional,” and this is an amateur film in many respects. It was rejected or overlooked by all the major festivals — Sundance, Rotterdam, Berlin, Cannes, Venice, Toronto, New York. But it turned up at three others I attended this year — Austin’s South by Southwest, Buenos Aires’s international festival of independent film, and Taos’s Talking Picture Festival. The jury I served on in Buenos Aires gave it a major prize, and it’s enthusiastically supported by filmmakers as diverse as Chantal Akerman and Peter Watkins. It will be showing three times next week at the Chicago festival, and though I wouldn’t call it the best film there, it’s in many ways the one I care about the most, the one that moves me the most deeply.

It’s a 168-minute narrative feature with some documentary elements about the impact of the Gulf War on this country, made over six years in New Mexico, and it expresses the rage and sorrow of Americans who were less than jubilant about that event while it was going on. None of this matters to most mainstream critics, who will continue to wonder why we don’t have any more political films. These are the same sort of people who periodically send out bulletins about the overall “health” of world cinema or American movies — pronouncements that are almost inevitably lies, because no one can see enough of the films made nowadays to make any such generalizations.

So far I’ve seen 20 of the features showing at the festival and would recommend at least 16 of them — an unusually high percentage. In rough order of preference, I’d place at the top Jean-Luc Godard’s 1964 Band of Outsiders, a sad and funny masterpiece that was an abject flop everywhere it played in 1964 but has become a treasured linchpin of American independent cinema. (Surely there’s some lesson to be found here.) Its durable charm has had a visible influence on Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise and more Hal Hartley features than I care to remember; even the name of Quentin Tarantino’s production company, Band Apart, is derived from the French title. It’s a festival critic’s choice selected by the Tribune’s Michael Wilmington, and the screening will be graced by an appearance of its leading lady, the sublime Anna Karina.

I can think of four other movies on the schedule I like almost as much: in alphabetical order, Abbas Kiarostami’s ABC Africa, William A. Wellman’s Track of the Cat, Richard Linklater’s Waking Life, and Tsai Ming-liang’s What Time Is It There? The Kiarostami is a documentary shot on digital video by the person I currently regard as our greatest living filmmaker — and by “our” I don’t mean he’s an American citizen. It’s a relatively minor work by Kiarostami’s standards but a major work by almost anyone else’s. Lamentably, the New York film festival rejected this Iranian film and accepted Majid Majidi’s relatively facile tearjerker Baran. Commendably, Chicago’s showing both — Baran is especially timely given its focus on Afghan refugees — though I wish the festival had also found room for Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s even more relevant The Sun Behind the Moon [later known as Kandahar], about Afghan amputees near the Iran border. Given the size and urgency of Uganda’s AIDS crisis, ABC Africa is timely as well — which makes it all the more regrettable that this film’s U.S. distributor has no plans to open it this year. Track of the Cat (my own festival critic’s choice — a Warners art movie in ‘Scope from 1954, shot in color but mainly designed in black and white) and Waking Life (Roger Ebert’s critic’s choice, an animated rendition of philosophical dialogues and reflections) are two of the most original movies ever made. No less singular is What Time Is It There?, Tsai Ming-liang’s most exciting work to date — a tragicomic reflection on death, time, and destiny expressed through witty visual rhymes between a young man in Taipei and a young woman in Paris.

Other favorites, in descending order of enthusiasm, include David Lynch’s soon-to-open Mulholland Drive; Wang Chao’s The Orphan of Anyang, the first hint I’ve seen of a modernist cinema in mainland China since last year’s Platform (it isn’t on the level of that landmark — which may be the greatest Chinese film I’ve ever seen, though it has yet to reach Chicago); Lucrecia Martel’s Argentinean La cienaga (a prime entry in the dysfunctional-family sweepstakes, though Track of the Cat is certainly a contender); Shohei Imamura’s irrepressibly goofy Warm Water Under a Red Bridge; and Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures, a documentary made by the filmmaker’s brother-in-law, Jan Harlan, which has both the advantages and disadvantages of an in-house production: candid glimpses, including such things as home movie excerpts, that add up to a portrait that seems both accurate and uncritical. My more guarded recommendations — meaning they’re perhaps worth seeing, but don’t say I didn’t warn you — would include Nanni Moretti’s Cannes prizewinner The Son’s Room, strong yet facile, like Majid Majidi’s work; Runaway, a documentary on teenage runaway girls in Iran by Kim Longinotto and Ziba Mir-Hosseini, directors of the much better Divorce Iranian Style; Hou Hsiao-hsien’s disappointing Millennium Mambo; and Catherine Breillat’s Fat Girl, with its promising material and horrible ending.

No festival can satisfy every taste, but I regret the absence of four of the very best films I saw in Toronto: Manoel de Oliveira’s I’m Going Home, Jean-Luc Godard’s Eloge de l’amour, Andre Techine’s Loin, and Laurent Cantet’s L’emploi du temps, the first and last of which are masterpieces. I haven’t yet seen Jacques Rivette’s Va savoir –which is also missing from the festival, though it will open in Chicago in mid-November. (Is it merely a coincidence that all five of these features are French?) Still, there’s so much valuable work on display here — work telling us things about ourselves as members of the larger world — that I can only urge you to see as much of it as you can.