From Cineaste (Spring 2010; Vol. XXXV, No. 2). Considering the continuing lack of contact between most Americans and the remainder of the world, it probably shouldn’t be too surprising to find James Wolcott still rattling on about the alleged French worship of Jerry Lewis in the September 2011 Vanity Fair — a myth addressed briefly in my second paragraph here, whose limited factual basis in fact hasn’t really been operative for almost half a century. As Lewis himself has often pointed out, his popularity in many places around the world has clearly surpassed his reputation in France. (Today, for instance, Woody Allen is immensely more popular there, with intellectuals as well as the general public — and more popular there than he has ever been in the U.S., which has never been true with Lewis.) But presumably this cherished piece of idiocy will continue to be trotted out as long as Americans remain clueless about France and its culture and proud of its ignorance. It’s a little bit like saying, “Oh, those naughty French — ooo-la-la!” — J.R.

Jerry Lewis

by Chris Fujiwara. Urbana/Chicago: University of Illinois Press,

162 pp., illus. Hardcover: $60.00. Paperback: $19.95.

I hope I can be forgiven for repeating an anecdote I recounted in these pages in 2004,while writing about Charlie Chaplin’s films on DVD. In a Swiss documentary about Chaplin in Switzerland, Charlie Chaplin: The Forgotten Years, his daughter Geraldine noted that when he discovered that his invitation to accept an honorary Oscar in the U.S. in 1972 came with a visa that allowed him to remain in the country for only two weeks, he was more delighted than indignant: “They’re still afraid of me!” he said with pride — or words to that effect.

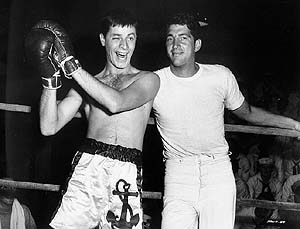

The curious process by which unreasoning love for Chaplin in the U.S. was transformed into unreasoning hatred is clearly matched by a comparable metamorphosis in the American psyche regarding Jerry Lewis. For me, the enduring mystery about Lewis isn’t any alleged love of “the French” for him — a factoid whose former (and always limited) relevance has by now been out of date for decades, ever since Woody Allen became far more revered in France than Lewis — but American denial about its own former Lewis infatuation, which was much larger than any French craze for the man could ever have been, and is even what made his French profile possible. (Just for starters, Martin and Lewis’s 1954 Living It Up made more money than Singin’ in the Rain, On the Waterfront, or The African Queen, and three years earlier, their third feature and biggest hit, Sailor Beware, was seen by an estimated 80 million people.) So Americans’ refusal to deal with Lewis having once been even bigger here than Elvis is the phenomenon that cries out for sociological inquiry, not the understandable respect and affection he continues to receive anywhere else in the world.

An interesting study could be written about why and how certain kinds of physical comedy can unleash such fear and loathing as well as infatuation, but this isn’t the sort of project Chris Fujiwara has in mind. Nevertheless, it’s hardly an exaggeration to say that his book, the 21st title to be published in James Naremore’s Contemporary Film Directors, is the first extended critical treatment of Lewis in English that Lewis deserves — including a thoughtful, sympathetic, and lucid (yet in no way sycophantic) 32-page interview that is conceivably the best one anyone has ever had with him. And considering that Lewis himself has already ordered a hundred copies of the book, it seems safe to assume that he probably agrees with me.

Why it’s taken so long for a filmmaker of Lewis’ stature to receive such treatment is a matter of some interest. But it’s arguably one of the virtues of Fujiwara’s compact study, rightly concluding that the important analytical work can begin only after the pseudo-controversy about Lewis’ importance is “settled,” to waste little of his space and time addressing this issue with any defensive polemics. Focusing on Lewis mainly as a director while retaining, as he puts it in his opening paragraph, “a sense of continuity in Lewis’s work in all its stages,” he never stoops to any form of defensiveness or special pleading while describing the unity and coherence of Lewis’s vision with the same confidence and scholarly thoroughness that he brought to Jacques Tourneur in his first book a little over a decade ago.

His pithy handling of what might be termed The Opposition occurs early on, after he notes in passing that Lewis’s films (as director and actor) in the early 60s “were reviewed more or less indistinguishably by American film critics (except that since [the 1965] Boeing Boeing, the only insignificant film among them, is a straight farce rather than slapstick comedy, Lewis, cast in a supporting role behind Tony Curtis, received praise for his restraint).” Fujiwara then briefly notes the more respectful French criticism published during the same period (his other comments in this book suggest that he has been especially attentive to Robert Benayoun), before adding, “The enthusiasm of French intellectuals (shared by the general public) for Lewis has given rise, in the United States, to countless lazy and patronizing jokes at his expense and at that of France from unthinking, conformist pundits — gibes whose ideological nature has become unmistakable and more obnoxious than ever in a period of U.S. history that has witnessed the rebranding of `Freedom Fries.’”

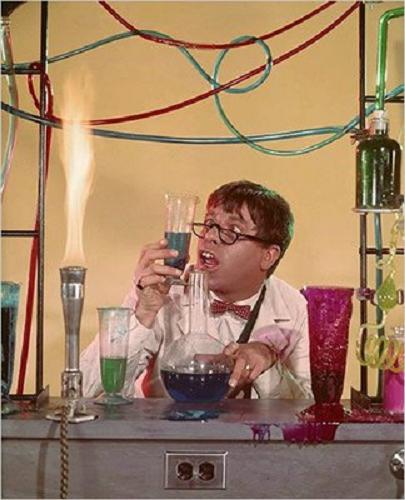

Afterwards, apart from a measured response to Andrew Sarris’s charge of sanctimonious moralizing and sentimentality in Lewis’s films, Fujiwara chooses to make his reply to Lewis’s critical detractors implicit in his overall argument. And what emerges most forcefully from this argument is the conviction that almost all of Lewis’s previous critics have erred by simplifying the work — trying to make it conform to diverse industrial norms relating to narrative, humor, and continuity that it meets only superficially and cursorily. Thus, “In discarding the surface logic of narrative and verisimilitude, Lewis’s cinema foregrounds its own structural logic. The viewer of a Lewis film follows the unfolding and application of the rules of construction that belong to the film — rules that are independent of the demands of narrative. This is Lewis’s formalist, materialist side.” This is an especially useful tip in approaching The Bellboy (1960) and The Ladies Man (1961), Lewis’s first two features, although curiously enough, it’s his fifth, The Patsy (1964), that Fujiwara identifies as “the most fully achieved of Lewis’s films”.

Halfway through his essay, while taking up the matter of “generic discontinuity,” which he sees as “a constant feature of Lewis’s work,” Fujiwara registers his conviction that several portions of this oeuvre aren’t especially funny (e.g., “the first half of Which Way to the Front?” [personally, I find the hysterical gibberish in the early scenes flat-out hilarious], “fairly long stretches of The Family Jewels and Hardly Working, and, perhaps, nearly all of One More Time”), adding that “One of my premises is that Lewis’s work creates an impure, shifting context within which such a lack need not be accounted a flaw.” This is a provocative assertion that warrants some elaboration, and I wish Fujiwara had gone further enough with it to reconcile this claim with my own feeling that some of the funniest moments in Lewis’s cinema — such as his character’s inability to cross the floor of his psychiatrist’s office without falling, in the early stretches of Cracking Up — are central rather than incidental to his overall achievement. (I suspect Fujiwara would agree with me on this score, but even so, I would have preferred it if he had spelled out this portion of his argument a bit more fully.)

If the above quotations suggest that Fujiwara’s case for Lewis is basically a formalist one, other portions of his essay (which is suggestively titled “An American Dream”) move his analysis in a quite different direction, with very fruitful results: “`Home’ does not exist in Lewis’s world. His biography offers an explanation for this absence: his parents, vaudeville performers, were constantly on the road.” (Although Fujiwara doesn’t mention this, the fact that Lewis’s parents failed to attend his bar mitzvah, as recounted in his 1982 book with Herb Gluck, Jerry Lewis in Person, is surely telling.)

And a page later: “Show business constitutes, for Lewis, an alternate psychoanalysis, a therapeutic sphere in which he acts out his obsessions in public and transcends them (see the confession scene in the prom in The Nutty Professor). In several films, Lewis depicts show business as an alternate family.” As Fujiwara notes, Lewis seems to be fully aware of this factor himself; in Dean and Me (A Love Story) — his 2005 memoir written with James Kaplan, which Fujiwara rightly terms as the best account of his early career — he says of Dean Martin and himself, in their meteoric rise to success, “What we really were, in a Freudian age of self-realization, was the explosion of the show-business id.” So it’s hardly surprising that the same comic who would later build elaborate gag sequences in Cracking Up (1983) derived from his near-brush with a suicide attempt and his open-heart surgery would in fact base most of his features on some of his most personal conflicts and issues.

It’s my own conviction that Lewis’s naked vulnerability as well as his courage in brandishing it partially accounts not only for his improvisational genius on live television at the onset of his career but also for the aforementioned fear and loathing in portions of his American audience more recently. Several years ago, during a period when he was appearing onstage as the Devil in Damn Yankees during its Chicago run, he graciously agreed to appear at an extended public q and a at Columbia College — a session that lasted, if memory serves, for at least three hours. The sense of risk and danger in the auditorium that afternoon was palpable, and it came, I think, from the fact that Lewis stayed so close to the edge of his emotions, seemingly as a matter of both policy and temperament. The possibilities of being hurt, and of hurt being transformed into anger and rage, were never entirely absent, even though he managed to keep his cool on the few occasions when one of the questions betrayed some hostility — hostility that may have derived in part from some of the tension generated.

For those commentators who wrongly maintain that Buddy Love in The Nutty Professor (1963) derives from Dean Martin and not from Lewis himself, the giddy megalomania of the man who spread his remarkable boarding-house set over two of Paramount’s soundstages in The Ladies Man (1961) and then filled them with nubile actresses has never been reconciled with the fumbling and bumbling idiot as well as the sexual panic of Lewis’ own persona within that space. Fujiwara has made a bracing start at mapping out the relationship between those two seemingly antithetical individuals, and better yet, has a pretty good idea of what these people might have to say to one another. — Jonathan Rosenbaum