From Moving Image Source [movingimagesource.us], posted March 5, 2009. The last time I checked, the box set Cinéma Cinémas was still available from French Amazon, for 25.56 Euros. — J.R.

How does one distinguish American cinephilia from the original, hardcore French brand? Based on an exchange I had with French critic Raymond Bellour and several other friends a dozen years ago — a round of letters first published in the French film magazine Trafic that later grew into a collection in English that I co-edited with Adrian Martin, Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia — there’s some disagreement about how serious a role French cinema actually plays in “classic” (i.e., French) cinephilia. According to Raymond, spurred in part by remarks from the late Serge Daney — a mutual friend and the founder of Trafic — modern French cinephilia was from the outset basically American, as suggested by the archetypal question, “How can one be a Hitchcocko-Hawksian?”:

It’s a question of theory, but even more of territory. This is what necessarily divides me from Jonathan, in whom cinephilia was born, like in everyone else, through the nouvelle vague, but who, as an American, takes the nouvelle vague itself as an object of cinephilia — whereas the cinephile, in the historical and French sense, trains his sights on the American cinema as an enchanted and closed world, a referential system sufficient to interpret the rest.

As someone who received much of my own training — or maybe I should say conditioning — as a cinephile during my five years as a Parisian (1969-’74), I can certainly see where Raymond is coming from. I’m old enough to remember a time prior to François Truffaut’s book-length interview with Alfred Hitchcock when regarding Hitchcock and Howard Hawks as serious artists was considered not only outlandish but somewhat deranged, even in France. Indeed, I owe much of my own excited rediscovery of American cinema to French film criticism of the ’50s and ’60s as well as Parisian programming of the ’60s and ’70s. But I also suspect that the reason why Daney could say something like, “The American cinema, how redundant,” is more that just the usual French taste for metaphysics and overstatement. Part of it, I would surmise, is the fact that French appreciation of American cinema was a natural and therefore invisible part of his and Raymond’s universe, something to be taken for granted, but an exotic extra-added attraction in my case.

I’ve been inspired to reflect further on this topic ever since my last visit to Paris, late last year, when I purchased a DVD box set devoted to Cinéma Cinémas, a French TV series constituting a sort of monument to hardcore cinephilia that lasted roughly a decade from early 1982 to sometime in 1991. Produced by Claude Ventura, and made up of various documentary and/or essayistic segments, this is a show I’ve been hearing about for ages from French friends. The four discs in this set contain a dozen episodes, each one including between six and 12 separate segments — with a grand total of 92 segments running anywhere from just under a minute to well over 20 minutes.

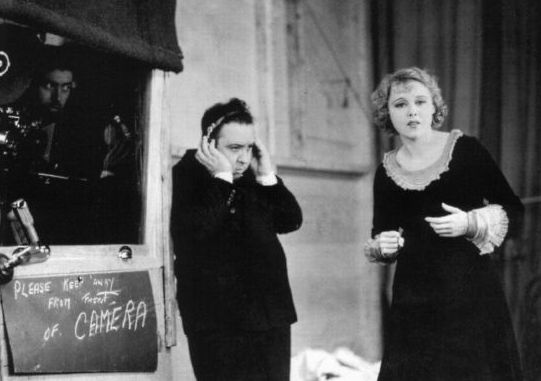

For the record, the shortest bit is a teasing, 45-second sound test Hitchcock made with actress Anny Ondra for Blackmail, his first talkie, in 1929; the longest, “Far From Philadelphia,” chronicles Philippe Garnier’s 1982 interviews in Hollywood with former associates of novelist-screenwriter David Goodis (a key French cult icon), most of whom barely remember the man. The sound test comes at the end of the 10th and final episode — devoted exclusively to Hitchcock, and including interviews with the master himself as well as Tippi Hedren, Janet Leigh, Anthony Perkins, James Stewart, and even Claude Chabrol, recounting the embarrassing accident involving an icy puddle that occurred when he and Truffaut set out to interview Hitchcock in the 1950s. (The Leigh and Hedren interviews, unsurprisingly but disappointingly, focus exclusively on the shower murder in Psycho and the sequence in The Birds when Hedren gets repeatedly attacked by birds — as if to ratify the common assumption that the assaults on Hitchcock’s heroines are what we most want to hear about.)

A few of the special bits — Jean Seberg’s 1957 screen test for Otto Preminger, Gig Young interviewing James Dean for a road safety commercial during the shooting of Giant — will already be familiar to some viewers from other sources. But much more — Orson Welles speaking at a lunch with members of the French press, Godard berating his crew during the shooting of Détective, Federico Fellini shooting a scene from his Satyricon, the comic low-budget writer-director-actor Luc Moullet hilariously describing his daily routines as a filmmaker, and Maurice Pialat shooting an early screen test with Sandrine Bonnaire, not to mention forthright, relatively no-spin interviews with Frank Capra, Angie Dickinson, Edward Dmytryk, Stanley Donen, Sterling Hayden, Rock Hudson, Aldo Ray, and Jane Russell — probably couldn’t be found anywhere else.

This isn’t a release designed for export, so the only subtitles to be found here are French ones whenever they’re needed (which, incidentally, is over half of the time). But American aficionados of American cinema — and American literature — who don’t speak French will still find loads of irreplaceable material here in English. On the first disc alone is Samuel Fuller in 1982 going through the first reel of his Pickup on South Street (1953) on an editing table with a running commentary; an interview with Richard Widmark during the shooting of Against All Odds (1984) that includes discussions of his co-star Jane Greer, Fuller, Don Siegel, Elia Kazan, and John Ford; and other interviews with screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides (They Drive by Night, Thieves Highway, Kiss Me Deadly), Siegel (who calls himself a “whore” on most of his pictures who envies the relative freedom enjoyed by Jean-Luc Godard, even though he adds that Godard envies him for the size of his budgets), Faye Dunaway, Martin Scorsese, and Sue Lyon (mainly about her experiences shooting Lolita). There’s also a bilingual 16-minute film called Jacumba Hotel in which an American woman reading aloud passages in English from Louise Brooks’s racy essay “On Location With Billy Wellman” alternates with a male voice in French giving shorter third-person accounts about Brooks while we watch clips from Beggars of Life (the 1928 Wellman feature she was shooting on location) and the camera snoops around what remains of some of the same locations in 1985, hotel included. Among the highlights on the other discs are a documentary about John Cassavetes directing and shooting three successive shots in Love Streams (followed by interviews with both Peter Falk and Ben Gazzara that are mainly about Cassavetes), Jack Lemmon talking about Some Like It Hot, Robert Mitchum talking about The Night of the Hunter, and features about John Fante, the deaths of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Rita Hayworth, and William Faulkner’s affair with Meta Carpenter (a script girl working for Howard Hawks) during the ’30s, while he was writing The Wild Palms.

In spite of these riches, many of which we could never hope to encounter on American cable or PBS, the most obvious challenge to Bellour’s thesis can be found in the fact that only about half of the segments in this monument to classic French cinephilia are strictly and exclusively devoted to American movies. And most of the rest focus on French cinema — directors such as Jacques Doillon and Jean-Pierre Mocky, actors such as Bernard Blier (the father of director Betrand Blier), Alain Delon, Catherine Deneuve, Jacques Dutronc, Charlotte Gainsbourg, the late Pascale Ogier, Dominique Sanda, and Michel Serrault — though there’s also room for the likes of Marco Ferreri, Aki Kaurismäki, Toshiro Mifune, Nanni Moretti, and even Lamberto Maggiorani, the working-class, Communist nonactor who starred in The Bicycle Thief (1948). And this leaves out the more eccentric and unclassifiable segments, such as a two-minute rumination by André S. Labarthe entitled “Le poids des mots” (“The Weight of Words”) in which French books devoted to Godard’s criticism, lengthy interviews with Fuller and Francesco Rosi, and scripts by Eric Rohmer and Jean Eustache are weighed successively on a butcher scale. (Labarthe, one should note, previously co-produced in the ’60s and ’70s the most ambitious and accomplished series of interviews with filmmakers ever undertaken by French television, Cinéastes de notre temps, and he’s also one of Ventura’s major collaborators here, along with Anne Andreu, Garnier, and Laurence Gavron.)

Speaking for myself, I’m fascinated by some of the information I’ve learned from this show — that Jane Russell prefers Gentlemen Prefer Blondes to all her other movies, that Stanley Donen sought to make musicals more stylized and artificial rather than more naturalistic, and that the late Don Siegel, in spite of his liberalism, looked back on his Dirty Harry and its success with a great deal of pride (leaving me to speculate whether he might have eventually revised his attitude if he’d lived much longer, as his more conservative protégé Clint Eastwood seemingly did when he made Gran Torino). This kind of film history may only be a supplement to what we already know on these subjects, but this series explored it with exemplary verve.