From Monthly Film Bulletin, Vol. 42, No. 501, October 1975. — J.R.

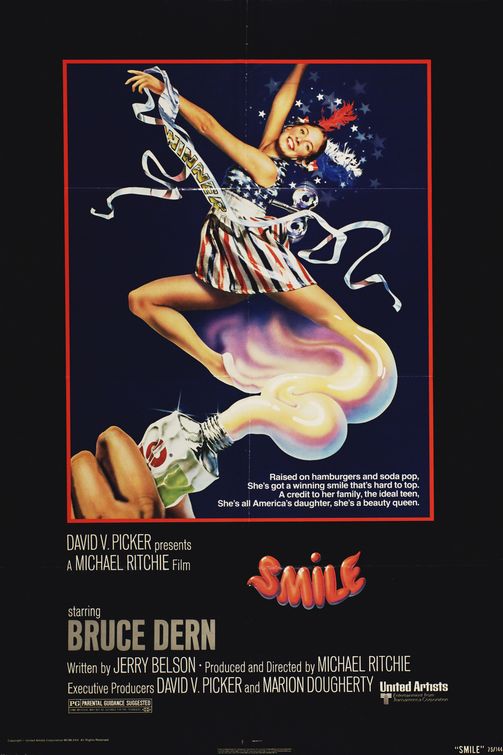

Smile

U.S.A., 1974Director: Michael Ritchie

Thirty-three high school girls arrive in Santa Rosa, California, to compete in the annual Young American Miss Pageant. While the girls rehearse their individual and collective performances and are interviewed by a panel of judges — including former pageant winner Brenda DiCarlo [Barbara Feldon] and car dealer “Big Bob” Freelander [Bruce Dern], who codirect the event – Brenda’s husband Andy [Nicholas Pryor], a heavy drinker who runs a trophy shop, derides the silliness of the pageant and Freelander’s son, “Little Bob” [Eric Shea], takes orders from his friends for Polaroid nude snapshots of the girls. Professional choreographer Tommy French [Michael Kidd] arrives to train the girls in dance routines, “Little Bob” his caught with his Polaroid while the girls are undressing, a nude snapshot is confiscated by the police, and he is taken to see a psychiatrist by his father. Andy complains to “big Bob” about his sexual problems with Brenda, and is reluctantly persuaded to attend the Exhausted Rooster Ceremony (for local men who reach the age of 35) that night, the second evening of the pageant. Fleeing from the ceremony, he has a fight with Brenda, and after threatening to shoot himself, changes his mind and shoots her instead, wounding her in the arm; she decides not to press charges, and “Big Bob” tries to cheer up Andy in jail the next day. French forfeits $500 out of his $2000 fee in order to have a special ramp put back when one of the contestants, Doria [Annette O’Toole], falls off the stage during rehearsals for the main event. That evening, the pageant winners are declared; the next day, the latter pose for publicity photographs, the others set about leaving Santa Rosa, and the nude snapshot taken by “Little Bob’ ends up clipped to the sun visor in a police car,

Considering the mainly `pointillist’ construction of Smile – composed almost exclusively of a mosaic of small gags, vignettes and details – any synopsis is bound to be somewhat arbitrary, and the one given above is no exception. If the principal attitude behind the mosaic recalls Nabokov’s observation that “Nothing is more exhilarating than philistine vulgarity”, it also sadly suggests the further observation that without the creative imagination of a Nabokov (or an Axelrod or a Tashlin or a Chabrol), exhilaration is prone to give way eventually to glibness or monotony. And the hilarity initially provoked by Michael Ritchie’s scattershot methods [and Jerry Belson’s script] gradually becomes more limited once it is apparent that the movie is after more than just giggles. Taking on a subject that automatically guarantees easy laughs – as H.L. Mencken discovered half a century ago, the hokiness of small-town America offers a bottomless well of possibilities – Smile quickly gravitates towards Ritchie’s familiar form of consensus filmmaking, in which something for everyone is strategically introduced to dilute the satire and provide it with a safety net: two relatively sophisticated and sympathetic contestants (Robin [Joan Prather] and Dora) are brought forward as identification figures; a local disgruntled outcast (Andy) shuffles to the fore like a refugee from a Sherwood Anderson tale to suggest a `serious’ critique of the community that is never quite delivered; the sarcastic Tommy French turns out to be an angel in disguise ; and after expending a great deal of effort to expose the absolute fatuity of the Young American Miss Pageant, Ritchie conscientiously whips up some fatuous suspense about who the final winners will be. On the level of superior TV blackout comedy, most of this works as long as the lively throwaway pace is sustained: the confrontation of “Big Bob” Freelander (Bruce Dern) with a psychiatrist is a particularly engaging demonstration of how wholesome, small-town normality can be seen, with only the slightest turn of the screw, as an aberration. But after bombarding the viewer with dozens of tiny absurdities and ready-made epiphanies – from TV dinners in the fridge and a mechanical bird in a cage to a reference to a “rodeo for the retarded” and a display of paintings accompanying a piano rendition of “Ebb Tide” – Ritchie exhibits a visible sense of strain when he wants to imply more solemn Moments of Reckoning. A long, `meaningful’ anecdote about Elizabeth Taylor, the Exhausted Rooster Ceremony, and the inadequately motivated glumness of “Big Bob” the following night, all of which seem intended as significant culminations of a sort, but are rather more like commercial breaks – Young American Director Pageants in which Ritchie himself appears to be awkwardly competing. He is much more confident skimming over the superficial aspects of his material, where all the gags are sufficiently brief and shallow to keep the texture light and rippling, even if the after-effects are immediately disposable.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM