Here are my reviews of two Malick films that I like much more than The Tree of Life, written almost a quarter of a century apart.

First, my review of Badlands from the November 1974 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin:

U.S.A., 1973

Director: Terrence Malick

It would hardly be an exaggeration to call the first half of Badlands a revelation -– one of the best literate examples of narrated American cinema since the early days of Welles and Polonsky. Compositions, actors, and lines interlock and click into place with irreducible economy and unerring precision, carrying us along before we have time to catch our breaths. It is probably not accidental than an early camera set-up of Kit on his garbage route recalls the framing of a neighborhood street that introduced us to the social world of Rebel Without a Cause: the doomed romanticism courted by Kit and dispassionately recounted by Holly immediately evokes the Fifties world of Nicholas Ray -– and more particularly, certain Ray-influenced (and narrated) works of Godard, like Pierrot le fou and Bande à part. Terrence Malick’s eye, narrative sense, and handling of affectless violence are all recognizably Godardian, but they flourish in a context more easily identified with Ray. Unmistakably Malick’s own, however, is the narration and dialogue: like the movie’s violence, it remains laconic, idiomatic, detached, and chillingly real throughout, whether it’s reflecting on the visual action, enriching it, compressing it, or sharply deviating from it (as when Holly narrates her uncertainty about whether Kit’s capture was deliberate –- in the past tense -– while we’re shown that it is). Less sustaining, alas, is the sense of discovery illuminating the film’s first part: the further that the couple proceed in their travels, the more familiar and twice-told their story seems to become, grasping after sociological observations that were interesting when they figured in Gun Crazy, Bonnie and Clyde, The Honeymoon Killers, Targets, et al., but are uncomfortably close to platitudes in 1974. The stylistic familiarities, on the other hand, appear too quickly and variously for them to fall into predictable patterns. Holly occupying a bed with an enormous dog; her disappointment with her first foray into sex, and Kit picking up a stone to commemorate the event (substituting a smaller one when he finds it too heavy); a balloon carrying souvenirs sent off for posterity; Holly’s father painting a primitive landscape on a billboard in the middle of a primitive landscape; the integration of Holly’s greenish dress with the blue hallway in her house; the lyrical interlude (worthy of Fahrenheit 451) of fire consuming the house, “distanced” by the use of silence and [Carl Orff and Gunild Keetman’s] “Musica Poetica”; the fairy-tale ambience and irony of the forest sojourn, Kit reading National Geographic while Holly muses pantheistically on the soundtrack; her attempt at small talk about a pet spider with a dying Cato [Ramon Bieri]; sepia newsreel-like glimpses of police and frightened townsfolk: all these are too striking as images and as ideas, and too neatly abstracted out of their immediate contexts, to fit into traditional genre expectations. But evidence of Kit’s cheerful craziness – delivering homespun advice about education into the rich man’s dictaphone, shooting a football that becomes “excess baggage” en route to Montana – appearing at first to be refreshingly non-psychological in implication, start to set up an inevitability of their own, suggesting both psychology and contrivance once they start to accumulate. As the landscape grows wider, and the literal and figurative notion of a destination for the couple grows increasingly remote, the story-line shrinks and stiffens, as though returning to its journalistic origins. (According to William Johnson, the plot is based on the exploits of Charles Starkweather and Caril Fugate across the Dakota badlands in 1958.) Carrying Kit to the airport, one of the deputies remarks to the other: “I’ll kiss your ass if he don’t look like James Dean”. The line, inflection, and the expression on the officer’s face are perfectly rendered, but we recall that Holly has already made this comparison (not to mention Malick himself, in an image echoing Giant), and sense the pressure of a director striving too forcibly to impose a point. Similar strictures apply to the repeated use of a Satie piece and Kit’s flamboyant farewell to his “fans” at the airport. But a long time will have to pass before one forgets the words, gestures, and faces of Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek — and hopefully a short one before the arrival of Terrence Malick’s second feature.

***

And here is my review of The Thin Red Line from the January 15, 1999 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The Thin Red Line

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Terrence Malick

With Sean Penn, Adrien Brody, Jim Caviezel, Ben Chaplin, John Cusack, Woody Harrelson, Elias Koteas, Nick Nolte, John C. Reilly, Arie Verveen, Dash Mihok, John Savage, John Travolta, and George Clooney.

Last week the National Society of Film Critics voted Out of Sight the year’s best picture, also awarding it best screenplay and best direction. If this baffles or bemuses you, you should know that the awards in each category are chosen by multiple ballots listing three titles in order of preference. What now seems like a collective preference for a sexy thriller over more ambitious pictures was in effect a tie-breaker between two irreconcilable positions.

As a participant in the meeting I saw partisans of Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan square off against partisans of The Thin Red Line, Terrence Malick’s first film since Days of Heaven (1978). Practically no one voted for both — only Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune comes to mind — so Steven Soderbergh lurched forward as a second choice, finally copping 28 votes while Spielberg and Malick tied for second place with 25 votes apiece. Like some of my colleagues, I wound up voting for Soderbergh along with Malick not because I favored Out of Sight but because I wanted to elbow out Spielberg; quite apart from my dislike of Saving Private Ryan, it seemed fruitless to throw the NSFC’s endorsement behind a movie that doesn’t need it. Apparently others felt the same: at the end of the day, Saving Private Ryan won no awards at all, and The Thin Red Line took only one, for John Toll’s cinematography. (According to Dave Kehr, a similar squaring off occurred at the NSFC 20 years ago when Days of Heaven tied with The Deer Hunter and the honors went to Get Out Your Handkerchiefs.)

The vote was meaningful to NSFC members even if it sounded like gibberish to the outside world: a split difference, one might say, between entertainment and art — between flag-waving and reflection, prose and poetry, public consensus and private reverie — though the actual winner engaged none of these issues. But in our ridiculously skewed culture, this dialectical distinction between Spielberg and Malick was arrived at almost as arbitrarily as the dark horse that broke ahead of both. Both films are about World War II and were made by major studios, but that’s about the extent of their similarity.

A person could more profitably compare The Thin Red Line, currently playing at McClurg Court, with Rob Tregenza’s Inside/Out, playing in a one-week run at Facets Multimedia Center (and Inside/Out is a Critic’s Choice this week in Section Two). But the parallels between these two epic experiments are pretty striking. Each is the third feature of a prodigiously talented middle-aged eccentric and original thinker with a background in existential philosophy that informs every artistic move he makes. Both films are shot in wide-screen 35-millimeter with Dolby sound (though Tregenza’s film is in black and white). And both filmmakers are passionately (and unfashionably) devoted to the aesthetics of silent cinema: The Thin Red Line makes as many visual references to F.W. Murnau’s Tabu (1931) as Days of Heaven makes to Murnau’s Sunrise (1927) and City Girl (1930), and Tregenza, who likes to film pantomimes in long shot, includes on his Web site a beautiful quotation from Luigi Pirandello that applies almost as well to Malick’s film: “The screenplay should remain a wordless art because it is essentially a medium for the expression of the unconscious.”

The films share narrative strategy as well. Both discard the conventions of a central character and a single story, running a relay between many disparate characters in the same rural setting, none of whom is subjected to any moral judgment. And both are a little too long for what they can achieve dramatically — Tregenza’s film is just under two hours, Malick’s just under three — but that’s because both are overly ambitious. If you agree with me that 90 percent of the movies made nowadays are insufficiently ambitious, being overly ambitious is a shared flaw that deserves our deepest respect. Both filmmakers value physical environment as much as “action” in the ordinary sense, and both — albeit in very different ways — use the cleavage and disruptions produced by World War II to reflect on the second half of the 20th century.

Yet they’re playing to different audiences in radically different venues. Inside/Out — made for a tiny fraction of the other picture’s budget, with no stars to speak of — has had too limited and piecemeal a national release since its 1997 premiere at Cannes to qualify even as a minor contender in any present or future NSFC awards, even in the experimental category. No articles about Inside/Out will show up in Vanity Fair or Premiere, no reviews will grace mainstream magazines or TV shows, no qualifying Oscar screenings will be held anywhere. Economically and culturally speaking — which in this country generally amounts to the same thing — the two pictures are never going to be permitted to inhabit the same universe. The fact that Tregenza’s distribution company, Cinema Parallel, has allowed us to see Michael Haneke’s The Seventh Continent, Bela Tarr’s Satantango, Jacques Rivette’s Up Down Fragile, and several recent films by Jean-Luc Godard locates him in a separate cosmos as far as most critics are concerned. So any context that can accommodate him and Malick has to be created by the audience.

I haven’t read the James Jones novel Malick based his film on, but Norman Mailer’s 1964 review of it sounds so relevant that I wonder if Malick might have read it: “Jones’s book is better remembered as satisfying, as if one had studied geology for a semester and now knew more. I suppose what was felt lacking is the curious sensuousness of combat, the soft lift of awe and pleasure that one was moving out onto the rim of the dead. If one was not too tired, there were times when a blade of grass coming out of the ground was as significant as the finger of Jehovah in the Sistine Chapel. And this was not because a blade of grass was necessarily in itself so beautiful, or because hitting the dirt was so sweet, but because the blade seemed to be a living part of the crack of small-arms fire and the palpable flotation of all the other souls in the platoon full of turd and glory.”

Mailer goes on to admit that Jones was not “altogether ignorant of this state,” and his and Jones’s macho sensibility is far from Malick’s vision. But few war movies have been as attentive to the significance and even the sanctity of a blade of grass, not to mention the sensuousness of “the crack of small-arms fire and the palpable flotation of all the souls” in a platoon, as The Thin Red Line. In Days of Heaven Malick’s preoccupation with the ecology made for wondrous images even when they seemed extraneous to the story, but this time they’re wedded solidly to the theme and the narrative, and the notion of a collective hero speaking from a single consciousness is powerfully articulated.

Malick’s intimate acquaintance with the aesthetics of silent cinema reaches well past Murnau. The punctuating shots of nature in the midst of combat — a wounded bird, a riddled leaf, a hill of waving grass — are pure silent-movie syntax, as is the notion of a collective war hero (often found in films and fiction about World War I; William March’s 1933 book Company K is one distinguished example). The poetic and philosophical internal monologues of Malick’s various soldiers, often paired with a sustained and soulful close-up of the character, are the structural equivalent of intertitles in silent films of the teens and 20s. This is a precious legacy that most major filmmakers of the 90s (excepting Godard, Tarr, Tregenza, Manuel de Oliveira, and a handful of others who live outside the Oscars sweepstakes) have either forgotten or never discovered in the first place — a sensibility that frees images from the tyranny of the sound track, allowing them to register in all their primordial power — and the major achievements of The Thin Red Line would be unthinkable without it.

Malick does this not to minimize the importance of spoken language in the film — most of which, apart from rudimentary exposition of character and situation, boils down to a running internal debate about “war in the heart of nature” (“Is there an avenging power in nature, not one power or two?”) and the claims of the material world versus transcendence — but to stress how detachable it is from the expressiveness of the images. In a way it all harks back to a manifesto about the sound film drafted by Sergei Eisenstein and cosigned by Vsevolod Pudovkin and Grigori Alexandrov in 1928, which argued, in capital letters no less, “THE FIRST EXPERIMENTAL WORK WITH SOUND MUST BE DIRECTED ALONG THE LINE OF ITS DISTINCT NONSYNCHRONIZATION WITH THE VISUAL IMAGES.”

Malick’s poetic and philosophical language — which periodically turns all his soldiers into soul-searching poets who share the same literary style, for better and for worse — is enhanced by this principle, which obliges us to confront the discourse on its own terms rather than as part of an unfolding plot. There are moments when the internal monologues dovetail into dialogue and vice versa, but overall this language creates a zone of reflection throughout the film quite separate from issues of plot, character, and history, a zone of spiritual self-interrogation that ultimately exists outside the coordinates of time and space governing the remainder of the film.

This is Malick’s triumph, but it also becomes his problem. To embrace silent film language is also to reclaim some of its ideological baggage, which in this case means denying the second half of the 20th century. Most of the period details seem accurate — though I wonder about one soldier’s recurring line, “I’m outta here” — but as a depiction of World War II it lacks any living sense of the 40s. (Some of the film’s defenders, thinking perhaps of the opening shot of a crocodile, claim that it encompasses the Vietnam experience. But while some moments recall Apocalypse Now and Platoon — Nick Nolte’s blustering colonel, the invasion and torching of a peasant village — these remind us more of movies about the war than the war itself.)

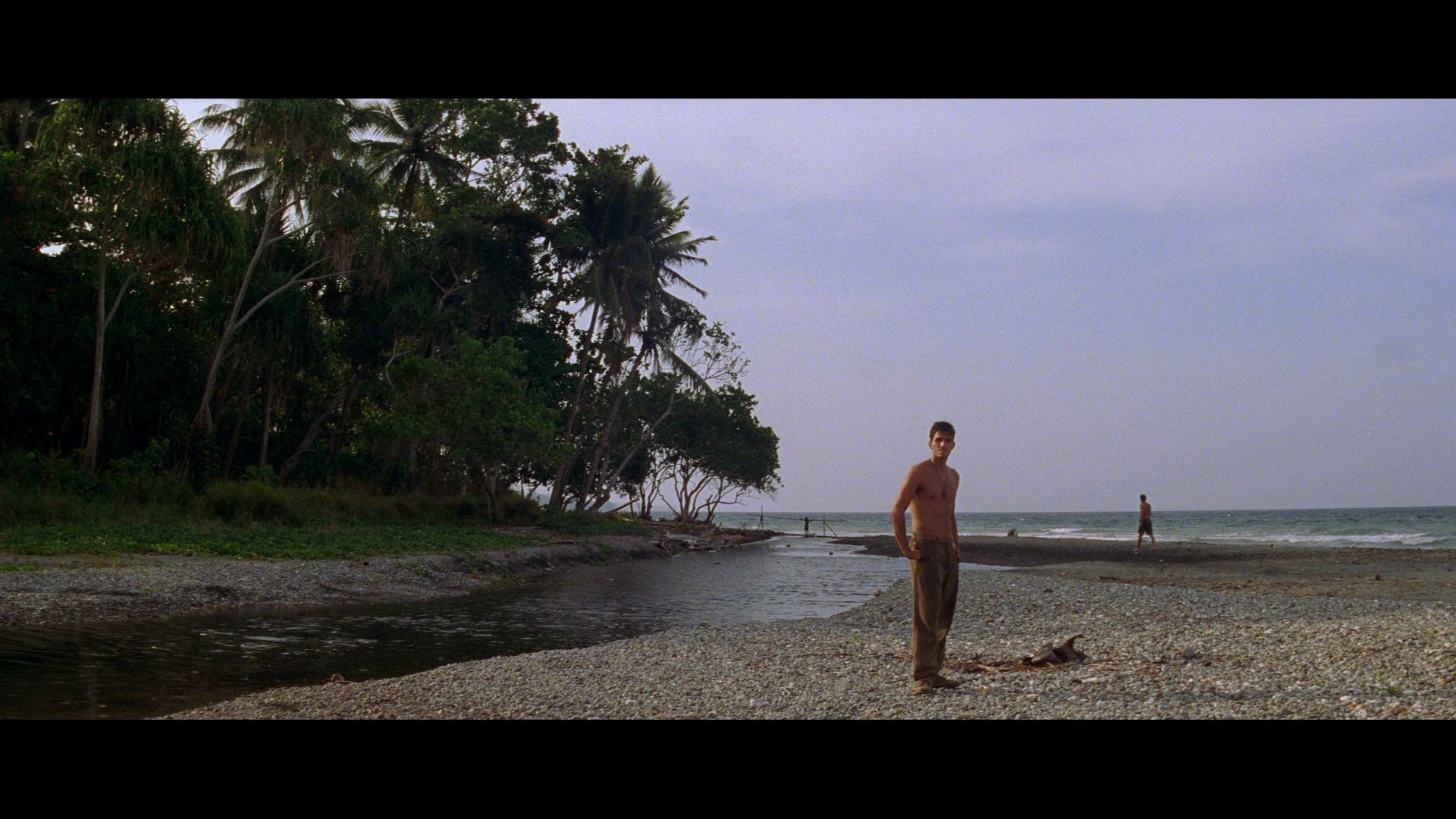

Before seeing Malick’s film, I asked a friend who’d been to an early screening whether it had much to say about World War II. He replied, “It’s more ambitious than that.” But expanding (or reducing) the issues and experiences of Guadalcanal to all wars can be an act of denial as well as courage, just as reducing (or expanding) a film about nature in Guadalcanal (actually filmed in the Daintree rain forest of Queensland, Australia) to a film about nature in general involves a comparable kind of shortchanging. In both cases, the level of abstraction needed to carry out the conceit can turn the film into a series of airy platitudes, divorced from history and geography alike. In some respects, Leo Tolstoy took a comparable risk when he decided that his theory of history as applied to Napoleon’s invasion of Russia somehow mattered more than the invasion itself. And while Malick may not be operating anywhere near Tolstoy’s level of achievement, his overreaching lands him in a similar kind of trouble.

To be sure, The Thin Red Line periodically rejuvenates the genre of epic war film in moral, sensual, and philosophical terms, at no point engaging in the sort of fatuous drum-beating that Joe Dante’s recent Small Soldiers makes such effective sport of. Sean Penn and Nick Nolte give the freshest and least rhetorical performances I’ve ever seen from them — not so much because Malick defines their characters complexly but because he refuses to judge them, leaving that to other characters whose assessments we can either accept or reject. (In the case of Nolte’s Colonel Tall, the colonel himself implicitly issues most of these judgments, progressively undercutting his own positions as he reassesses the wisdom of his decisions.) Other actors (Elias Koteas, John Travolta in a smaller part) shine in this environment, and Toll’s cinematography is lustrous throughout. The film is full of excitements and beauties, but all three times I’ve seen it, it starts to defeat me by the third hour because the level of generality isn’t sustained by enough particularity. I become sufficiently detached from Malick’s own level of detachment to become bored, and then to start wondering what he had to omit about this war and its terrain for his generalizations to make sense.

In a discussion we had about the film in the on-line magazine Slate, critic David Edelstein described for me the film’s “mythos”: “We begin in Eden, we go to hell, we return to Eden.” Malick’s Eden recalls Murnau’s Polynesian Eden in Tabu: the latter is polluted by “civilization” just as Malick’s Eden is polluted by war, with the expressionist arrival of a fateful ship. But images like these depend on our ignorance of both places, a desire for innocence that’s touching but debilitating. Not as debilitating as our willful innocence about war, which Saving Private Ryan ultimately caters to, but debilitating all the same: in The Thin Red Line the peaceful, frolicking Melanesians come to us through Private Witt (Jim Caviezel), whose affection and soulful compassion for them gets more screen time than the natives themselves. When Japanese soldiers belatedly enter the picture, we may be so grateful to Malick for refusing to stylize them as villains that we may overlook his mythologizing of their “simple” humanity. This is the negative side of Malick’s embrace of silent cinema, but it shouldn’t dissuade anyone from rushing off to see The Thin Red Line before it closes (which is likely to happen fairly soon). Whatever its limitations, it’s the most impressive work to date in Malick’s splintered career.